Blackbird Interactive’s spaceship-recycling simulator Hardspace: Shipbreaker is a game about the exploitation of labor. When all the Earth’s resources are used up, mankind industrializes outer space. You play as a newly recruited Shipbreaker, a blue-collar worker seduced by the infinite potential of the cosmos. “Boundless Promise. Limitless Resources. A Brighter Future,” begins your automated Lynx onboarding experience. “It’s here that hard workers like you, the backbone of civilization, will help us pave the way to the galaxy.”

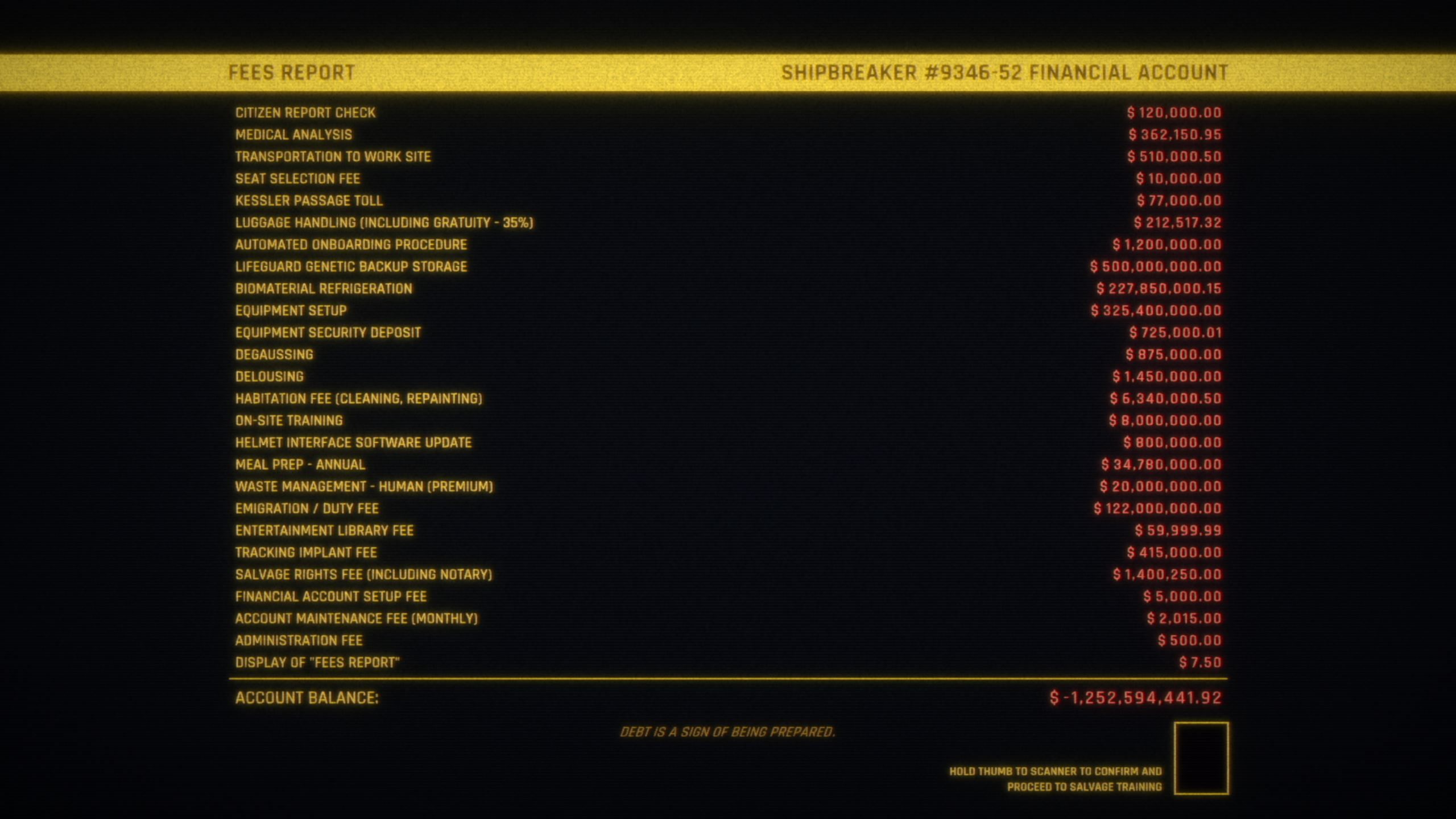

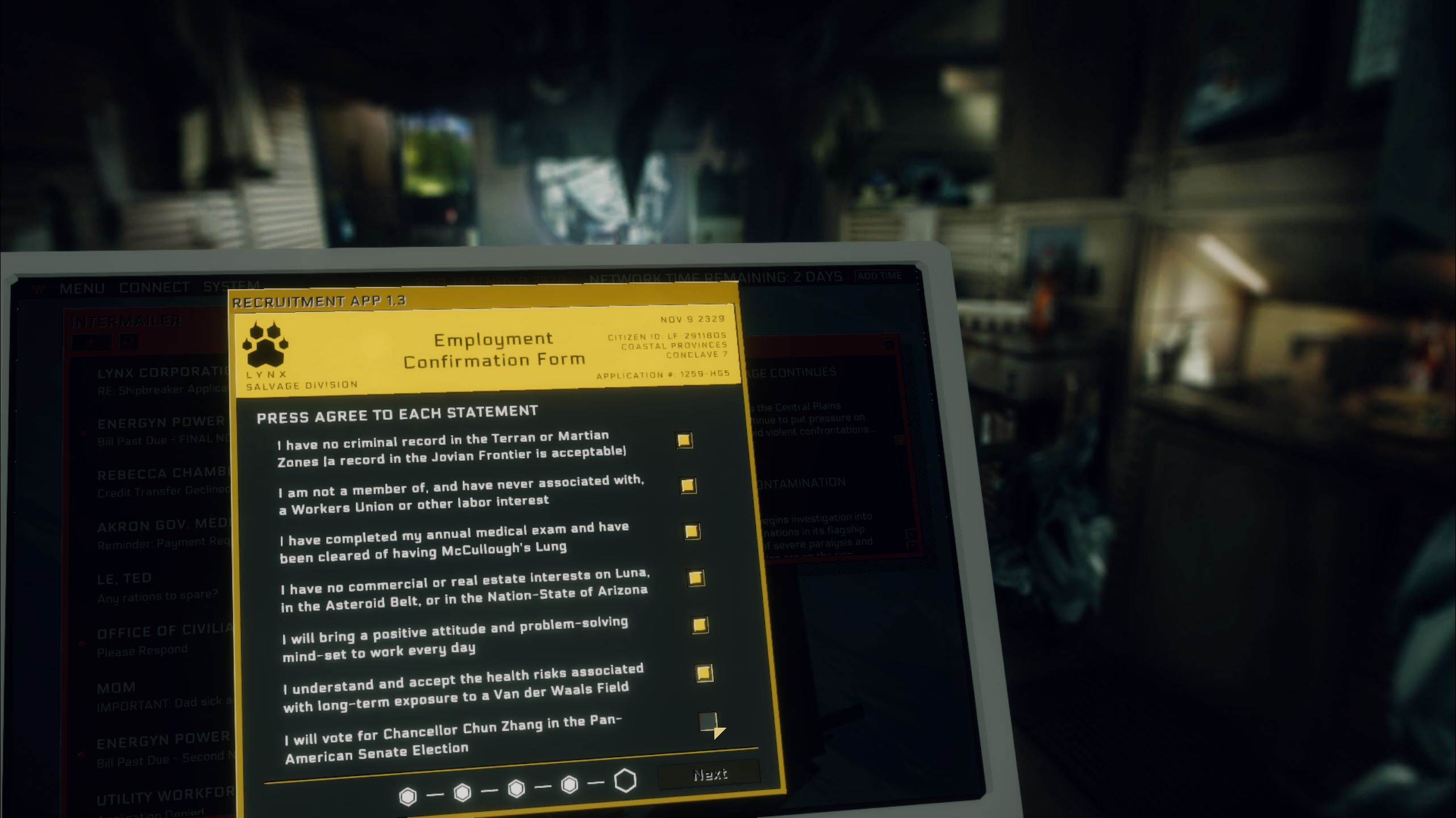

Before you can get started working on the endless, dangerous grind of dismantling derelict ships, you first must sign a contract that, among other things, makes you swear that you’ve never associated with a worker’s union or labor interest. Then, you’re saddled with over a billion dollars of debt that must be paid back to the company before any profit can be made. You also have to sign up for the Everwork Asset Replacement Program, a process that kills you and collects your DNA so that you can be infinitely cloned by Lynx anytime you accidentally perish at work. Before you ever step foot onto the job site, you have to literally die for the company.

After a few days on the job, you receive an email from another Shipbreaker. “You probably noticed LYNX doesn’t exactly take great care of us,” they say. “I don’t blame ‘em… they don’t really have a reason to. Up until about a hundred years ago workers like us would make groups called Unions and fight for better wages, safer work, decent hours… that kinda thing. Basically balance things so people don’t just get exploited to hell. Lynx was actual key in gettin’ rid of all that.”

After this, you’ll start getting the Salvage Workers Unite newsletter, which outlines the key demands the organization plans to make of Lynx. They want the debt canceled, new workplace safety measures, and perhaps most importantly, they want the clause removed from the contract that states Lynx own the rights to each employee's genetic sequence. By the end of the first act, Lynx has caught wind of Salvage Workers Unite and announces that enforcers will be sent out to each site in order to stamp out any union efforts.

In this interstellar industrial revolution, the exploited workers of Lynx are in the early stages of their own labor movement. It’s a story that mirrors our past while critiquing our present under the doctrines of capitalism and the ever-expanding influence of corporate power. While the poorest and most undereducated are often the greatest victims of exploitation, this is, of course, not exclusively a blue-collar problem. As BBI continues to develop the story of Hardspace while it’s in early access, the games industry itself is on the cusp of its own labor movement. What does it mean to make a game about organized labor and exploited workers when the industry itself is currently facing similar issues?

“I’ve thought quite a bit about it in the last few weeks actually, and I’m glad we told that story,” Blackbird Interactive’s chief creative officer Rory McGuire says. “Because I think it sets us up as a company to then have that conversation, which we might not have if it was some other game.” According to McGuire and Elliot Hudson, the director of Hardspace: Shipbreaker, the causes and solutions behind workplace exploitation in the games industry are more complex than they’re portrayed in their game.

“A lot of industry outsiders think of it as some cigar-chomping executive that just says everybody needs to work,” McGuire says. “It’s usually not. They come with a smile, and it’s your friends and compatriots who are working late… this was very woven into the industry until about five years ago when people started talking meaningfully about change.”

In a way, the game industry's labor problem is more insidious than the one presented in Hardspace. Rather than signing predatory contracts or being seduced by false promises like a Shipbreaker, game devs often fall victim to more systemic issues that are much harder to recognize. A lot of the harm being caused to devs is a consequence of crunch culture. Developers want to give it their all, so they put in more and more time and energy in order to keep up with their co-workers — who are also being overworked. “With Blackbird, we avoid [crunching] and we actively try to avoid people working overtime,” McGuire explains. “But we don’t lie to ourselves. We know that people are still working overtime. I tell Elliot: ‘Don’t work overtime’, but I know he does. To actually fix it is quite a big action. It’s a cultural issue.”

While the Lynx corporation deploys enforcers on the job site to stamp out the union effort, McGuire says that for the game industry, companies recognize that worker issues like crunch are bad for employees, and therefore, bad for the company. “I think in the modern era of games most companies acknowledge at the highest levels that crunch is bad and that they want to move away from it,” McGuire explains. “But it’s much more interleaved into the identity of the company or the identity of the industry. Crunch is fucking horrible for the industry. There’s countless studies [that show] after just two weeks of crunch, productivity falls, and no company crunches for just two weeks. They crunch for months and months.” The effect of extended crunch isn’t just productivity loss, but the inevitable burn out of developers. “You destroy your employees,” McGuire says. “So you invest in your employees, which is actually the biggest cost on the business side, and then you destroy them.”

According to Hudson, the game industry is stuck in a vicious cycle of crunch and burn out, in part, because there is no organized labor in the game industry. “One of the factors that leads to [burn out] is the lack of systematization and standardization in game development,” Hudson explains. “Every game project feels like you’re doing everything from scratch because you lost all of the people that had that knowledge, you burned them out and they left. That’s not the only reason, but it’s a big contributing factor, which then makes crunch something that has to happen more often, which then burns people out more. It’s a terrible feedback loop.”

“It’s not sustainable,” Hudson says. “I think regulation is what makes it sustainable.”

As confident as McGuire and Hudson are about the necessity for organized labor in the game industry, they’re less sure about the path it needs to take to get there. The global game industry has gotten by for decades by self-regulating and ignoring these problems that have now become cultural and systemic. “I think the unfortunate thing is that to build that framework now is a lot harder than it was even 40-50 years ago,” McGuire explains. “Even if it doesn’t happen like Union as a name, I do think it needs to be a future of employees put higher in the industry.”