A soldier wearing the weathered scepticism of war-privy eyes; a farmer with a drive for democracy in a veiled dictatorship designed to drown it; a vestal priestess who knows more of the gods than any god-willing mortal should even comprehend. Back in late 2015, a sprawling and ambitious Skyrim mod set in an ancient underground metropolis launched to unanimous critical acclaim. Now, almost six years later, The Forgotten City has somehow managed to supersede its origins and become one of the most unequivocally impressive games of 2021. But to borrow a term from history, this long and arduous evolution - magnificent as its final form may be - was nothing short of an odyssey.

Across the board in game development, there are an innumerable amount of hurdles that are both insurmountable and necessary to conquer. That might sound paradoxical - it is - but it’s why video games are, in a sincerely accurate sense of the term, one of the closest things we have to modern magic. For Nick Pearce, game director at Modern Storyteller, hurdles started to appear before he was even at the gate, let alone out of it. His original effort became the first mod to ever win a Writer’s Guild award, but it was still emphatically that - a mod, developed using a toolkit provided by an intensely rich and corporatocratic publishing behemoth. The story was his, but ownership is a tricky subject in contemporary art.

“There’s a term in the EULA for the modding toolkit, which says, ‘You can't commercialise these mods in any way,’” Pearce tells me. “It's debatable whether or not taking your idea for a mod and turning it into a standalone game amounts to commercialization. I'd argue that it doesn't, but there's ambiguity there.”

Pearce, a former lawyer, went to Bethesda - which he’s careful to avoid mentioning by name - and explained his situation: he wanted to make a game based on his original story but without any assets or IP from the studio’s proprietary toolkit. He was eventually granted permission to pursue his goal, although this just distilled what was ostensibly one problem into multiple newer - and arguably larger - ones.

“It was an all-consuming obsession for four and a half years,” Pearce explains. “In the beginning, when I first had the idea, there were three major initial obstacles. The first one was I didn't have any time, the second was I didn't have a budget, and the third was I didn't have any idea how to make a game.

“The first issue I solved by just quitting my job, which was ridiculously risky. I was working as a legal strategy advisor to a big tech company, so by leaving, my opportunity cost was an absolute fortune - the cost of a house. I got some money by applying for grants and digging into my savings. And to make a game, I knew I wasn't going to be able to do it on my own because it was just too ambitious a project. I hired a really awesome Unreal Engine programmer - I think of him [Alex Goss] as a one-man army, because he coded a game which most other studios would have put two or three programmers on.”

Throughout my conversation with Pearce, each and every one of these hurdles is described both candidly and with a sense of calmness that implies it was little more than a drop in an overwhelmingly larger ocean. My previous mention of problems being distilled into more problems becomes increasingly apt - yes, Pearce had won the rights to his story and overcome the initial issues of having no time, no money, and no idea about game development. The Forgotten City was still just a concept though - the real war of attrition was yet to even begin.

“There are a lot of challenges subsequently,” Pearce says. “The big one is funding. When you're making an indie game, you're always running out of runway. So it's like, alright, I've got this grant money, but that's only gonna last me three months. How am I going to do that? If I run out, the team falls apart and the project's done. There's a huge amount of pressure to just keep bringing funding in.”

It’s worth noting at this point that The Forgotten City was made by just three people - Pearce, Goss, and John Eyre, an artist - with a small amount of outsourcing offering additional aid. Throughout the entire development cycle, the team never even had the budget to hire an animator - this posed a much larger threat to the project than you might imagine.

“We were attempting something that narrative games just don't do,” Pearce explains. “If you think back over the years to Firewatch, Ethan Carter, The Stanley Parable, and Dear Esther, all these amazing, narrative-driven games - the one thing they have in common is they feel like big empty worlds because they don't have any characters. And the reason they don't have characters is because it's exceptionally difficult.”

When The Forgotten City launched last month, the most universal critique of it - which I also made in my own review - was that the character animations were a little awry. Pearce tells me that this exact criticism has been floated ever since the game was revealed. In an early impressions piece on the first trailer, PC Gamer called the animations “incredibly janky.” According to Pearce, “that burned” - and so he set up a Zoom call with Obsidian lead animator Shon Stewart and asked him to school the team on how to get more out of what little they were working with.

“I was absolutely determined to make sure that people had a really good time with it,” Pearce explains. “I think part of that determination goes back to what I'd given up to become a game developer. I walked away from a pretty great career. I mean, it wasn't always exciting, but I'd spent ten years working to get pretty good at being a lawyer.

“I always had in the back of my mind, if I fail, if I fuck this up and the game flops, then I've walked away from a ten-year career for nothing. And that was terrifying. It would have been embarrassing, but also it would have been devastating because I can't go back. There's this weird thing with the legal profession where if you spend too much time out of it, you can't get back in because the skills and experience atrophy over time. So I had to make it work. When PC Gamer publicly bags your game and says it's incredibly janky, it's a wake up call. You’ve got to rise to the challenge because there’s no other option.”

Pearce’s ambition and drive are evident from everything he says in our interview. To this day, the first thing he does when he wakes up in the morning is check Twitter to see how people are responding to the game. As well as obviously being happy with the positive reception, he also makes a point to recognise bugs in need of triaging and constantly looks for ways to improve the game. This is evidenced by the fact the team recently pushed patch 1.2.1, which remedies almost all of the major bugs that have surfaced over the last few weeks.

It seems apt now, after having discussed that the game is out and rapidly progressing towards its final, finished state, to honour its central time-loop mechanic by going right back to the beginning. Where did The Forgotten City come from? How did such a novel premise come about? What caused Nick Pearce, a career lawyer living in comfort and content, to make perhaps the largest and most precarious leap of his life in order to give us what is possibly the single best game of 2021?

“The first thing I did when I was learning to mod was build a hallway,” Pearce says. “And that hallway evolved into this big, ancient underground city. I thought, well, I've got this cool city, but it's just a big empty space, and I don't like those. So what am I going to do to make this interesting? Then I had this idea: ‘Okay, wouldn't it be cool if we could travel back in time to see what the city used to be like when people lived there, and meet them to find out what happened and why the city is no longer inhabited.’

“In the beginning, I'd written this story where you had to figure out who was responsible for destroying the city. And in the first draft of the story, the person who destroyed the city was you. It was kind of like a Philip K. Dick, sci-fi twist. I showed it to a friend and he goes, ‘Yeah, looks pretty cool, but you’re basically just gonna make people feel really guilty.’ Because whatever you do, you're the one who destroyed the city - nothing you can do about it, you're gonna get railroaded into doing this thing that kills everybody.

This is what ultimately paved the way for both the game’s central time-loop mechanic and the Golden Rule that serves as its narrative foundation. Pearce describes the original mod as “a pretty amateurish project, a rough first draft of something I didn’t ever expect to get any serious attention.” But with this newfound dedication to expanding on its ideas in an organic and intelligent way, he was able to take the best and leave the rest. Perhaps the most prominent example of this can be seen in the fact that the city is fundamentally Roman, but Roman culture was largely stolen from Ancient Greece. Over the course of four years, this realisation quickly became the core building block in The Forgotten City’s remarkably intricate structure. Unbeknownst to himself at the time, Pearce had cracked the code.

Major spoilers for The Forgotten City follow.

“I was reading a bit more about Underworld mythology and I noticed something that struck me as being really fascinating,” Pearce tells me. “Not only did the Greeks and Romans have this idea of Charon, the ferryman of the dead who helps the newly deceased cross the river that separates the land of the living from the land of the dead - the Ancient Egyptians had that as well. They had a deity called Kherty, who was this ram-headed deity who also sailed the deceased on a barque to the Underworld. And then I just went, not only do they have the concept of the underworld - they've got a concept of a person who ferries people to the underworld in a boat and its name starts with the same consonant.

“Either that means the Greeks plagiarised that idea from the Egyptians, which is almost certainly the case, or it's a wild coincidence. I kept reading other mythology literature and listened to some podcasts, and I learned about how the Sumerians in previous generations similarly had the concept of the Underworld and this ferryman of the dead called Khumut-tabal. And it just clicked for me that these civilizations have been copying from each other since right back at the beginning of the cradle of civilization. I hadn't really heard that idea expressed - I've never seen anyone put those points together and turn it into a story thread. I wanted to have a go at bringing to light this really fascinating series of events, this common thread throughout the history of all these civilizations.

“And not just telling people about it, but actually showing it to them one layer at a time. So we start with the Roman city, and then underneath that you've got the Greek level, then the Egyptian level and then the Sumerian level. And so the whole thing becomes this allegory for the way human civilizations and their stories are built on top of each other. We take what we need from people and then we build something on top of what they've done and just forget about the origin. That ties back to the whole concept of the game, and indeed the name, The Forgotten City. We take things from people and then we forget all about it. It's fascinating to remember how little is new in the world. Layering those revelations one at a time was really important, because if I just presented you with influences from all four civilizations at the same time, that would have been hard for people to make sense of, right? But by having those layers and forcing the player to go underground - instead of linear progression, you just go deeper and deeper and deeper - that was a way of structuring those revelations in a way to make them make sense.”

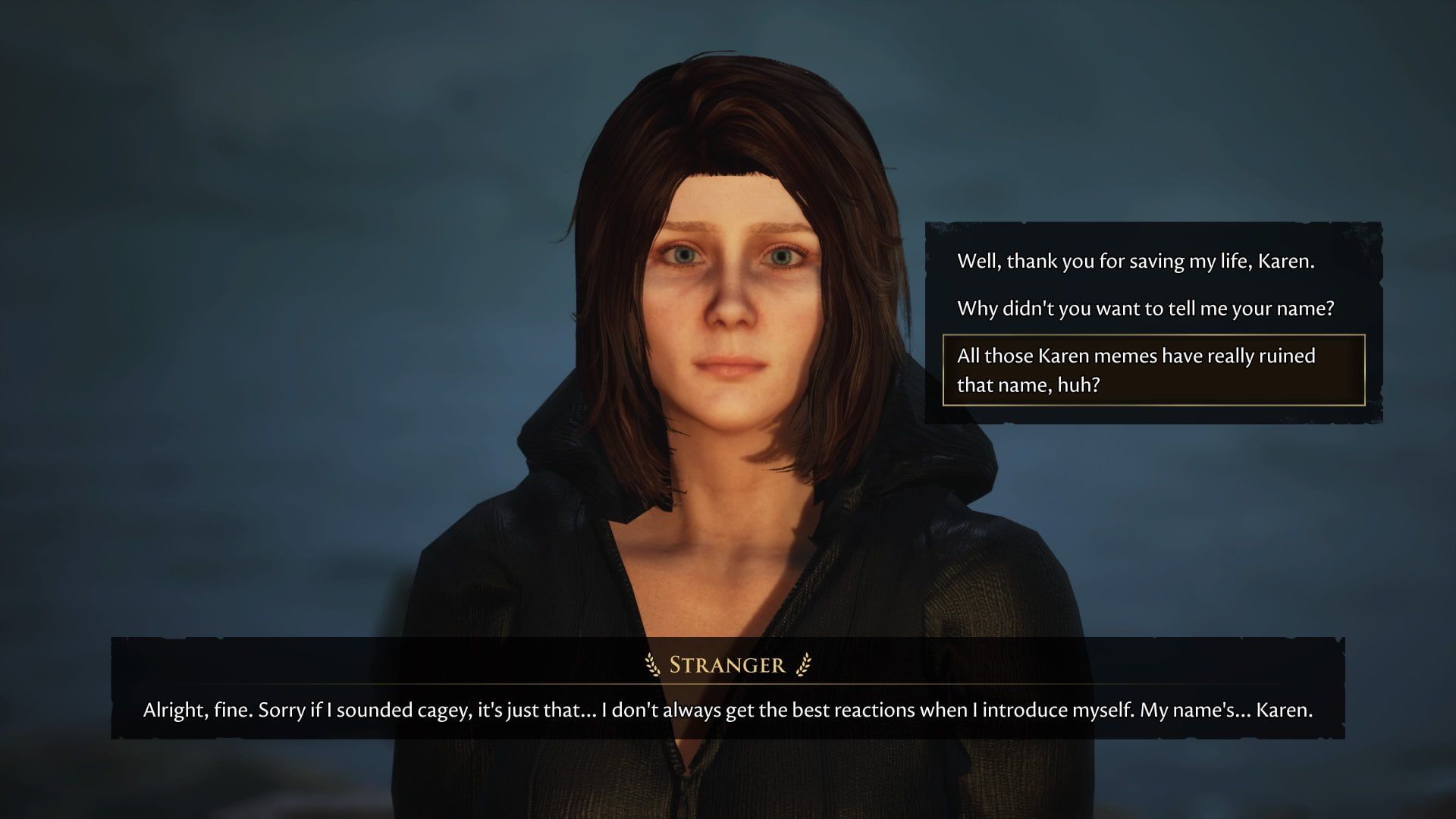

Pearce’s emphasis on the Charon connection is pertinent to one of The Forgotten City’s most successful and, strangely, polarising ideas. At the beginning of the game you’re introduced to a woman named Karen. She’s wearing a black hoodie and is standing by a river, claiming that you washed ashore with nothing on your person other than a strange, unrecognisable coin. She asks you to go look for her pal, Al, and after creating your character, the game begins in earnest. To some people, calling this character Karen was worthy of a good old-fashioned eyebrow raise - what is Modern Storyteller playing at here? For anyone willing to give the game a chance to explain itself, however, this ostensibly cheap joke would gradually grow into one of the game’s most subtly brilliant and remarkably intelligent ideas.

“I don't think I've heard a single person say they got it immediately,” Pearce says. “I think one of the reasons people don't get it is that Karen is such an on the nose name - you can't call a character Karen in fiction. In an earlier draft of the story she was called Karen and my tester was like, ‘What are you doing? You can't call a character Karen, that's just stupid. That name is off limits because as soon as people hear it they just think of the memes.’ So I wrote that into it and allowed the player to react. At the start if you ask her name she says, ‘Hey, I’m Karen. She'll be reluctant and coy, she’ll say, ‘Oh, I don't always get the best reaction when I introduce myself, my name's Karen.’ And she's thinking, I don't want to tell people my name because I'm Charon, the ferryman of the dead. But you're thinking she doesn't want to tell me her name because her name sucks.

“You can even sass her if you want, you can say those memes have really ruined that name, and she says, ‘Yeah, something like that.’ I gave players the opportunity to react to the stupidity of that name choice in a realistic way, and that distracts them. A lot of people don't like that lore - a lot of people found it tonally incongruous, which it is. My position is always just, ‘Wait for it. It's gonna make sense.’”

The Forgotten City also makes use of other contemporary references for eventual effect. While the Karen/Charon riff is central to the game’s story, there are also other, smaller instances of contemporaneity that are intended to play on the idea of how inherently valuable it is to place an immediately modern protagonist in an ancient setting.

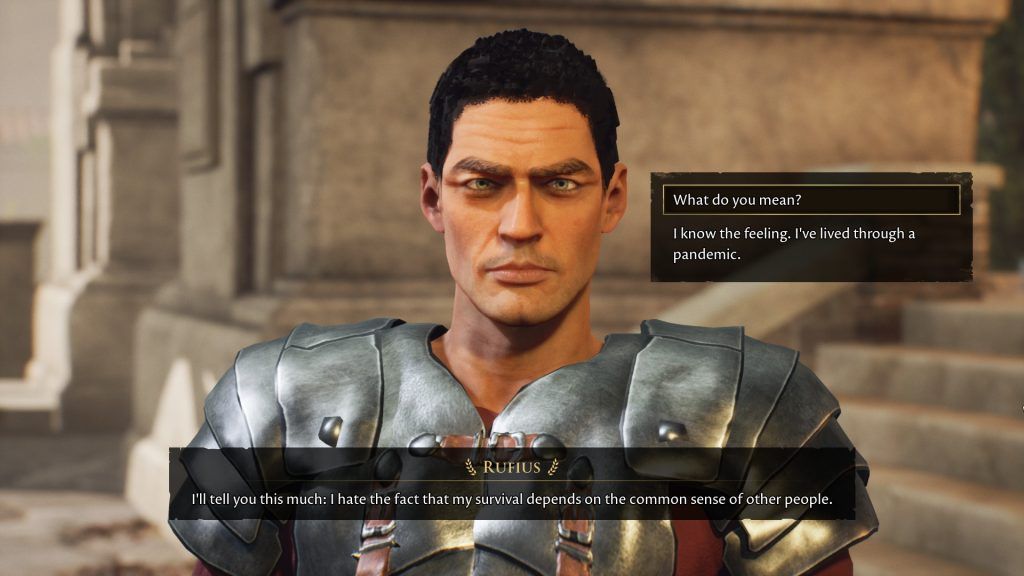

“The pandemic reference just occurred to me as I was telling this fantastical story,” Pearce says. “A city where if one person sins everyone dies is really far-fetched, and so we really need people to suspend their disbelief. One of the ways we did that was by couching it in terms of decimation, the practice where the Romans would kill one in ten of their soldiers, but times ten. And so we tried to make it feel a bit less far-fetched by embedding it in this framework of decimation and mythology around Midas and Medusa, and Equitia’s story about Baucis and Philemon and how the gods wiped this city off the map because they failed a morality test.

“I tried to make players relate to that by creating this analogy to the pandemic, even if it was just brief. Anyone who's walked around the streets of their own city right now and been horrified by the number of people taking zero precautions can relate to Rufius’ comment on being horrified by his survival being subject to other people’s common sense.”

It’s fascinating that Pearce brings up Rufius here. If you’ve played the game, you’ll likely already know Rufius’ deal - he harasses Vergil for being gay, but does so as a result of his own rheumatism and internal confusion. When I ask Pearce about this story - its impact and intent - he explains that it is both historically accurate and grounded in thematic context that, to this day, is vital for understanding how we as a people can be more accepting of both ourselves and others.

“What I tried to do was create a complex and sympathetic character in Rufius,” Pearce tells me. “Rather than just a straight up villain, I tried to come up with some plausible reasons why this character might be acting unreasonably and a way for the player to unpick that. I've known someone who did suffer from rheumatism, and it can be not just physically painful, but cause depression and serious mental health issues. So this character is dealing with a whole bunch of complex simultaneous issues. There's rheumatism and he's struggling with the way he's feeling internally, and also trying to reconcile that with his faith. The combination of those issues culminated with him lashing out at this perfectly decent gay dude.

“I wanted to give players the opportunity to intervene in that, and also make Rufius sympathetic enough that in the epilogue when you see them together in the museum it doesn’t feel too contrived. You can see how Rufius, underneath his gruff exterior and confusion, is still a decent person who is somewhat sympathetic and has the potential to improve. I think that's one of the mistakes you can make by portraying homophobic people as two dimensional villains. People make mistakes, that’s the whole point of the story. But they also have the potential to learn and change the way they think and evolve.”

Speaking of the canon ending in the museum, in order to get there, you obviously need to master The Forgotten City’s central time loop. They’re a funny thing, time loops - the discourse around Twelve Minutes is recent, unequivocal proof of how messy they can be when they aren’t handled with the right kind of nuance and tact. In an era of uninspired and often incoherent time-loop games, what X-factor allowed The Forgotten City to define itself as a titan among toddlers?

“When I was rewriting the story, I went back and watched Groundhog Day,” Pearce tells me. “One of the best things about Groundhog Day is the sense of fun, and it's fun because Phil Connors is not in any particular danger. He’s this slightly cynical character who realises he can do whatever he wants and get away with it. And so he goes and gets into fatal accidents and romances all sorts of people and learns new skills and sends people to get hurt or step in puddles. He really exploits the time loop in a whole bunch of different ways - it's really playful and enjoyable to watch.

“I wanted to capture that sense of playfulness and fun. Even though The Forgotten City can be a bit dark at times, there's also funnier stuff and plenty of opportunities for the player to experiment and goof around and exploit the knowledge they have from previous time loops in a fun way. I think, to other devs who are looking at making a time loop game, you can't forget that it can't just be clever, it has to be fun. And if you’re not doing that then you've missed something fundamental about what a time loop means and what it allows.”

As an example of this, Pearce cites The Forgotten City’s “totally historically authentic” Roman ziplines.

“Just for the record I want to say that's ironic. But at the same time, there's no reason to think the Romans couldn't have made them. Romans had ropes, they had pulleys, and they had wooden handlebars. There’s no reason they couldn't have done it, we just don't have any evidence they did. But we also don't know that they didn’t.”

Pearce’s journey is a long and storied one. After four years of intense development and iterating on stunningly smart and novel ideas, his work has clearly been recognised with the acclaim it deserves. But how does he feel now, four years after quitting his job and with the game of his dreams officially under his belt and out there for the world to play?

“Think of it as Schrodinger’s video game, in the sense that it was simultaneously a masterpiece and a piece of shit,” Pearce says. “Because I had lost all objectivity about it, I had no idea which it was, so for me it was just both. The only way to find out was by opening the box and releasing it.

“I was in two minds about the game the entire time I was making it. In the end, I just tried not to think about it and focused on making the best game I could without trying to anticipate the outcome. I mean, obviously when you make a game you hope it will be as commercially successful as possible. But in terms of setting realistic targets… Most people in this industry, their goal is not so lofty as to make millions of dollars, it's literally to stay in the game, to live to tell another story. If you can make enough money that you have the opportunity to make another game, that is a pragmatic version of success. If that sounds a bit sad, it's very much the reality of the industry. Making a video game is extremely difficult. It's hugely time-consuming and it's fiercely competitive because there are so many games being made all the time. Just surviving well enough to make another game is a measure of success for most devs. I think that's true of me as well - I made this game because I love making games. And if I can continue doing that, then that's awesome.”

Speaking of which...

“Alex and I would like to make another game,” Pearce says. “I hope we've carved out a bit of a niche by making intelligent and thoughtful story-driven games for intelligent and thoughtful adults. I hope we can continue carving that out and use the success of The Forgotten City as a benchmark and also a way of trying to communicate to people what we’re about and the kind of stories we want to tell. We've got a few ideas I'm excited about at the moment. They're all narrative-related. I just need a bit of time to unpack and figure out which of the three ideas has the most promise, and then begin working on it.

“I've been so busy frantically trying to put out spot fires and fix bugs that I haven't really had a moment to relax and enjoy the feedback. While it's a relief that people like it, I haven't really taken stock or processed anything. And because we're under lockdown here in Melbourne, we haven't been able to get together for a beer to celebrate or anything so it feels a bit anticlimactic. Hopefully we’ll be able to have that proper beer soon as a team.”