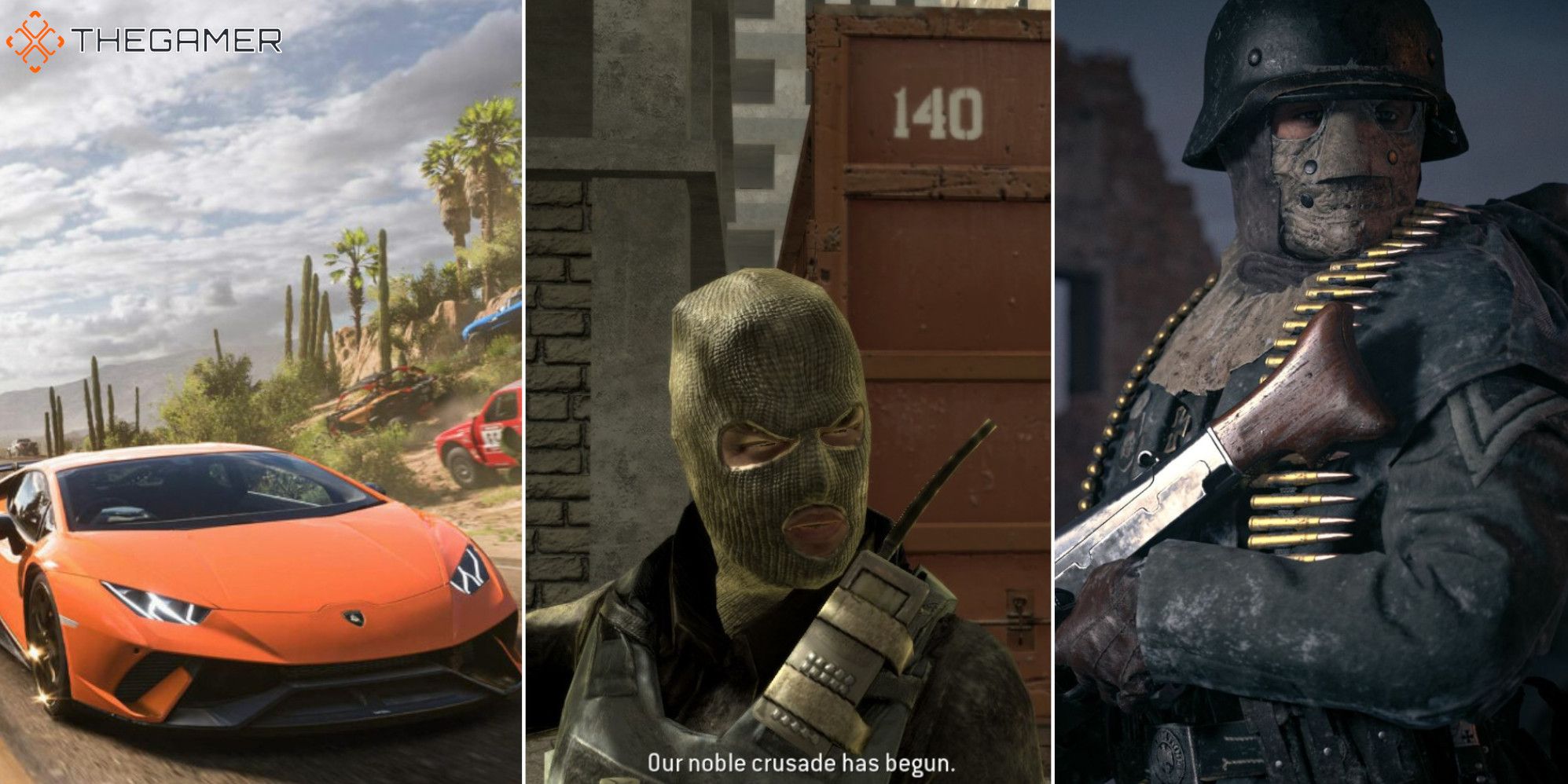

Muslims and Arabs are still deeply misunderstood and underrepresented in video games - both in the finished products and behind the scenes - as several recent events have proved. Forza Horizon 5 bans names like Osama and Nazih, Call of Duty: Vanguard included pages of the Quran strewn across the floor, and the Arabic at the end of the Arcane premier was completely broken - it wasn’t cursive and it was back to front. The current state of representation in the industry needs to change, and change soon.

“I think what we're seeing is not necessarily that games have changed much,” says Rami Ismail, an indie developer and co-founder of Vlambeer. “I think games have remained pretty similar and there is underrepresentation and marginalisation of Arab and Middle Eastern viewpoints throughout the industry. The biggest change you're seeing is it's harder to ignore the region [and] culture of the people because a) they're more prominent in the industry, b) the market over there is growing rapidly.

“You're seeing all these larger companies trying to make an effort to fit into the region to open local publishing offices, marketing departments, and realising the stuff they've been making has been, and continues to be, offensive or misrepresentative. They've just never had to deal with it because all the criticism was in Arabic and they couldn't read it.”

Since Muslim players noticed the inclusion of a desecrated Quran in Vanguard, the Call of Duty team issued a response from its Middle Eastern Twitter account. But this is not a Middle Eastern issue, it’s a Muslim issue, and the vast majority of the world’s Muslims live outside that region.

“It’s really complicated to communicate to people that Arab issues and Muslim issues are two completely separate things,” Ismail says. “It's a very logical PR response. The backlash will mostly happen in Arabic, so they're apologising only in Arabic not to notify anybody else that they've made a mistake. I get why they're doing it. It's still bad.”

Around the same time as this, players discovered Forza Horizon 5 wouldn’t let them use some very common Arabic names in the custom license plates. “I expected that, because the previous Forza Horizon didn't allow me to [use my name],” says Nazih Fares, head of localisation and communications at The 4 Winds. “All major publishers started entering the Middle East or have been [there] for many years - the likes of Ubisoft, EA, etc. You would expect things like that would finally start evolving because it's a typical list of things - names, wording strings, syntax, and stuff like that - that get caught [by profanity filters].

“The gaming industry is evolving into all aspects, like adding pronouns in games, adding accessibility features for different types of disabilities and whatnot. I'm one of those [people] that use those [features]. I'm partially colourblind so it's always helpful to get these options. But when you get to a situation like, ‘Oh, my name is blacklisted,’ it triggers these typical experiences of going to the US and always being that person that will get extra screening, just because of my name.

“These simple things could have been fixed by now. After many, many years in the industry, most of these Arabic names are going to get flagged because they are linked to a story - Osama being Osama bin Laden, my name being Nazi. I had the same experience with PSN, when they started adding the real ID feature. They force you to write your legal name so that when there's customer support stuff they can ask your name. My name is not allowed to be used in that instance, which makes no sense. Why do I have to write Nazeeh? Or Osama needs to write Usama? It's not a compromise we should [need] in these modern times.”

While this may seem like a small issue, it betrays a wider Western perspective on Arabs, the SWANA region (Southwest Asia and North Africa), and Muslims. “The Western approach of looking at the Middle East is, ‘We know the Middle East, I've been to Dubai - I've seen these towers and this weird utopia,’” says Fares. “Or, ‘I've heard of the Middle East, my brother served in Iraq and fought.’ It's always the two extremes, there's nothing in between talking about the positivity of the changes and everything that's happening there. Like Lebanon having a gay pride [parade], a certain cleric starting to say maybe there is nothing wrong with same-sex relationships and stuff like that.”

But what’s the solution to this? More Arabs and Muslims are in game dev than ever before and these mistakes are still happening. “We can start by educating the key leadership,” says Fares. “People in publishing groups or in development and studios.”

But that’s not all. Fares also believes more infrastructure is needed in these underrepresented and misunderstood regions so that locals can make games themselves. “It's going to take years, but we don't mind doing the hard work because it's going to pay off for everyone,” Fares says. “My personal goal would be to finally say, ‘Yes, there is [a] proper gaming [industry with] studios and publishers in that region that are not just bringing talent from abroad and making them work there. Instead, they're nurturing and, like Britain, elevating the local talent from the regions.’”

One Triple-A developer, who wished to go by the pseudonym Robin, has a more charitable response to the issues. “I think they extrapolated a banned names list that has existed within the Microsoft database for a while and they just implemented it without checking and asking if it’s still relevant, offensive, culturally sensitive,” they tell me. “Given how much accessibility and representation [there is] within this Forza, it came off as super odd. When you [see] a generic Arabic name like Osama is banned for no apparent reason beyond the hysteria of the name Osama, it comes off as odd.”

Other Microsoft titles do allow some of the banned names, so it seems each developer has its own list, rather than a centralised one. “Osama was accepted in AoE [Age of Empires] whereas within Forza Horizon it’s banned,” Robin explains. “Even Mohammed was banned [in the past] because some developers were afraid of it backfiring on them because it’s the name of the prophet, not really understanding Mohammed is the most common name on Earth.

“I don’t think it came from a place of ill intent. It’s more a lack of proper research, updating, and content check. Similar to what’s happened with Call of Duty and the Muslim crisis they’ve unfortunately stumbled upon.”

Like Fares, Robin believes that change has to come from within companies. “If you just rely on what someone from the Western world perceives as correct you’re going to be robbing the privilege from someone else,” Robin says. “I really hope companies move towards [forming] content inclusion or review committees that allow them to look at the content they’re trying to achieve within the game and not look at them via the eyes of one ethnicity or culture. It’s not only that companies need to hire more diverse talents, they need to create the cadences to support feedback from [them], otherwise, you’re still going to make mistakes.”

A line of broken Arabic, banned names, and a few pages of a book may seem like innocuous, innocent mistakes, but ultimately, the general consensus of all those I spoke to is summarised perfectly by Robin. “It shows that we still have a long way to go as an industry in terms of nailing down representation and making sure that the content we present in our games is actually authentic and not offensive.”