The game Closed Hands is a 130,000-word text-based game, developed by Passenger Games. The game is free to play on Microsoft Windows, Linux, and Macintosh operating systems. Closed Hands explores the effects of extremism on different communities, as it is centered around a terrorist attack in a fictional location in the UK. We sat down with the developer, Dan Hett, who has a personal connection to the game after losing his brother in the Manchester bombing in 2017, following an Ariana Grande concert. In Closed Hands, Dan has used his personal experience to challenge what constitutes our perception of what a video game actually is and to explore complex ideas surrounding extremism.

In this piece, we’ve focused on the game design aspects of the interview. To learn more about how Dan explores the intricacies of extremism in the game, you can read that interview here.

TheGamer: Heavy content can sometimes be exhausting, even if we come out of it having gained a great experience by the end. With unflinching work like this, there’s still a threshold for people and for us as writers too. Do you think that threshold is higher for a game like this that’s all narrative as opposed to an action game where you play as the hero, such as Call of Duty?

Dan Hett: Yeah, I think so. I think the depiction in games is very wide ranging. We use the word unflinching quite a lot when we talk about this game intentionally, because it doesn't look away. But then if you look at something like the Russian scene in Call of Duty, that is just gratuitous, almost to a cartoonish degree. And I can totally imagine what that writing session was like when they said, ‘oh, we're going to do this scene: you're going to come out of an elevator, you're going to be in the role of the person mowing people down in the airport.’ But really, no one's playing Call of Duty for the narrative. When I first played it years and years ago, I didn't really even understand the narrative point of it. It was just targets. And I don't read about it years later. When I did play that, I understood that kind of presentation is a lot more cartoonish. But then you've got things in the middle that I think do quite well at this but are misunderstood.

For example, you've got things like Spec Ops: The Line. As a knee jerk reaction to it, you will look at that and go, “this is a war shooting game, I don't care.” Obviously, there is so much in that. And it does things beautifully. It presents things very well. It plays with the format as well. The first few hours of play, you're just shooting shit. And then you start to realize that there's depth to this that is not apparent. And I think that kind of gave us a nice middle ground. For me, it’s a huge inspiration on my work in that it's using the form in completely new ways to tell stories. But things like that also kind of made me worried because there is a section within the gamers who vehemently dislike this kind of shit. And I understand it up to a point. But it's difficult to make work that pushes things forward and challenges players without kicking the hornet's nest.

TG: What made you decide to make this a text-based game?

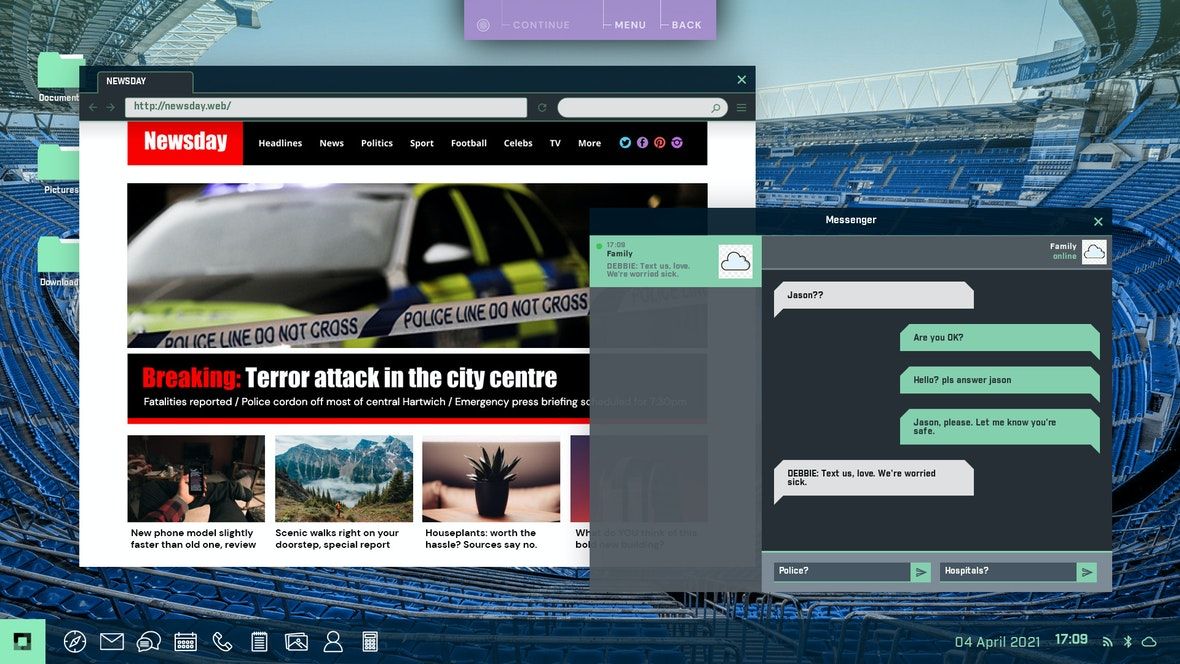

DH: So, I think the way in which you present stories means the response in the audience can be different. And one of the reasons that we chose text was that there is nuance and subtlety that it gives us that I think you would lose if we were doing dialogue boxes, characters, and things.

You take an audience expectation and mess with it, and then present them with something they're not necessarily expecting, which is what games like Spec Ops do. We’re telling people that this is 130,000 words and 150 scenes of super intense and unflinching content in a difficult game about extremism. The kind of person that is going to interact with this knows what they're getting into. And it's more of an arts crowd than a games crowd. But I do wonder if we’d pitched this a bit differently, would we have attracted a different crowd? Would they have expected something different, and would they have been surprised by it? I'm not sure. But I think there's a lot to be said about just how you describe things. So, it's always been quite tricky quantifying what this thing is and isn't really.

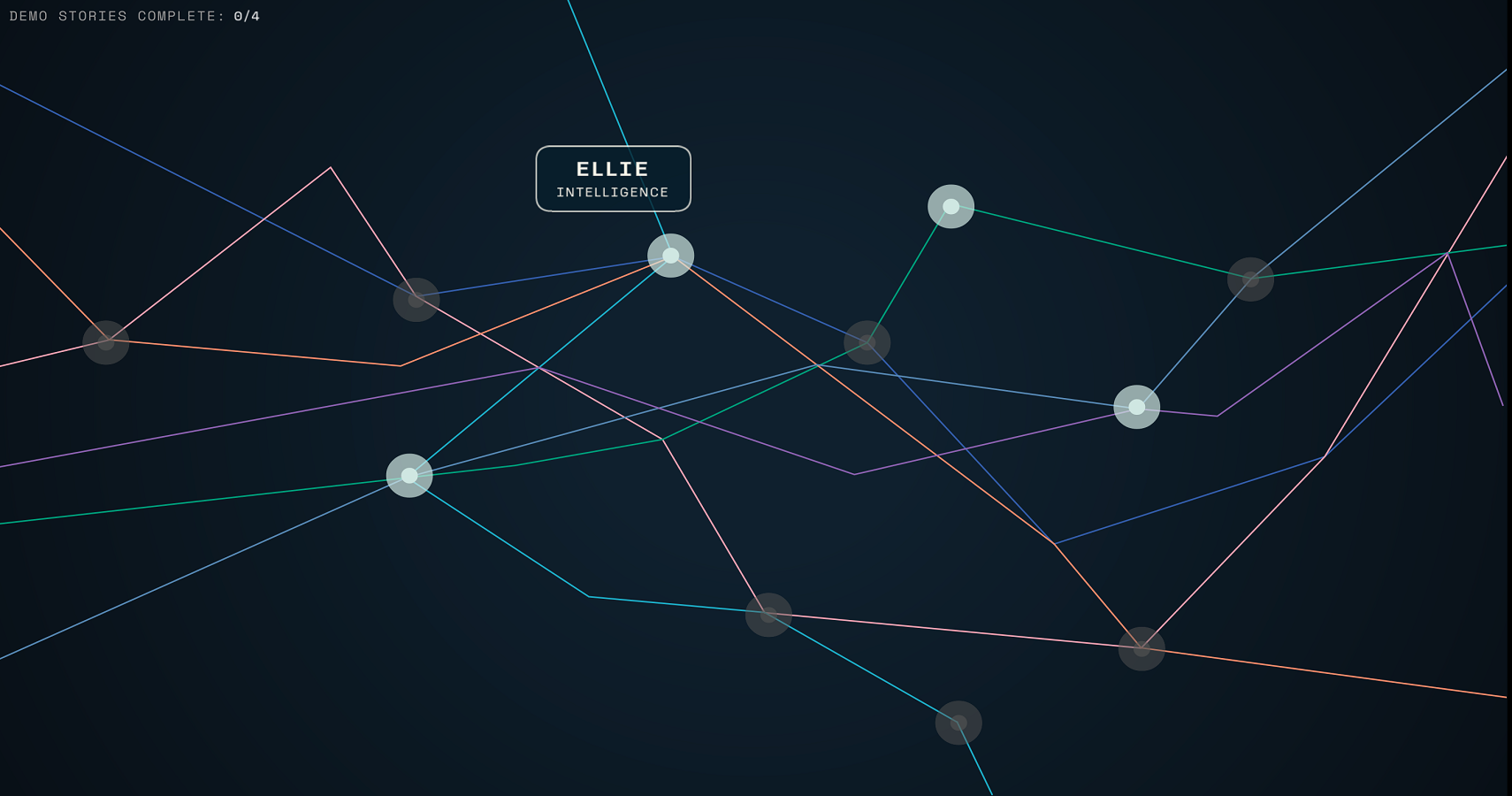

TG: This game is set up as a kind of spider-web design, where the player can either jump around between different characters in the story, or they can focus on one storyline and play that through before switching to others. What made you decide to use this web structure as opposed to a straight narrative?

DH: We experimented with presenting that story in different ways. The original version of the game was going to be hard timelines—horizontally—and they would be time-based. And we ended up going with this much more abstract field, which I think sort of facilitates both kinds of play, where some people will want an hour or two of a very snappy single story, and some won’t.

I think, for example, like with TV, they're scratching the surface of this a little bit. You’ve got Bandersnatch, which in TV terms was bringing revolution. It was incredible. But in interactive fiction terms, it was actually a fairly standardized branching narrative. It was just: pick one of these two things, then pick another two things. At the end, it didn't do anything particularly clever. But in TV terms, the audience was just blown away by it. Bandersnatch needed tech and needed to build a system that would let you pick things and all this other stuff. But I'm way more interested in, for example, the thing I'm pitching to Sky. It’s just traditional television, filmed as traditional Hollywood, but is written in such a way that it's completely influenced by games. And that's kind of what we're trying to figure out. Is the audience ready for this kind of complex story in the media, not necessarily just games? Because I think there's a lot of people out there who would engage with this but don't know that you can do this stuff.

TG: The plot of the game is based around “the incident.” What made you decide to omit the incident itself and instead focus on the responses to the incident?

DH: One of the core designs of the whole thing was: we are not depicting this attack. We don't talk about the nature of it. There was no narrative benefit in terms of what we wanted to create with this that would justify a really gratuitous scene showing the attack.

There are a couple of reasons that we’ve pulled the camera back a level. The story is about the cause and effect, and it's about the city, its inhabitants, and the whole spectrum of people that are affected by this stuff. If in telling Yasin’s [one of the characters who implemented the incident] story directly, the player was making decisions for him, that was a pair of shoes that I didn't want to put the player in. The story is one that we wanted to tell, but when you're making decisions for a character, you're inhabiting them, and you are part of that story. You have agency. [While some decisions] in Closed Hands are quite throwaway, some of them are really meaningful. And it felt very strange, giving the player the option to make a decision as somebody like that. It didn't feel right. And so, the question then became: how can we tell this story? And what happened? Where can we place the camera that we're going to capture the story, and we're going to understand not just the effects on him and his decisions, but more importantly, the effects on his family and his community?

TG: Who was your target audience with this game?

DH: For us, we had two halves of the audience. Firstly, people playing games and consuming games, [but ones] who aren't necessarily playing games that are talking about challenging things. That's kind of a given. But I'm way more interested in people who don't already play games than those that might already interact with them. [There are the people that] read a lot of the intimacies of cinema or television or documentaries, and they have no idea that video games are doing this or that there are video games that they can play and not need a tutorial, since it's just text. And we tried to leave the door open as much as possible.

But being able to release it for free is super important. And it just means that the barrier to entry is very, very low. You don't need a really good computer to run it. We were supported by the Arts Council, which makes us quite unique as well. To our knowledge, we're the first major games work to be sponsored by the Arts Council. So, everybody got paid, lock down happened, and we were supported. When we released it, we didn't have to sell 10,000 copies to make sure everybody was paid, and that that felt quite nice. So, what we've done is we've released it for free. It will always be free, we're never going to charge for it. But this signifies to us that funders, like the Arts Council, are starting to see the value of video games for storytelling.

I think we are slightly unique in that respect. And it's interesting, because we don't really want to be unique. We want loads of casual games in the future. I tweeted to that effect recently to say that one thing we do hope to do is just open the door to more games creators being funded like this, because other countries have got it nailed down. Canada and America are quite good at this stuff. And the UK, I think if we can just push the door open a little bit and enable other voices to come through in games, then mission accomplished.

TG: Have you done any other projects like this one before?

DH: There were three small projects that I did in advance of this that were much more personal works around grief and my involvement in the Manchester attack and all that stuff. One of them was called The Lost Levels. It was an arcade cabinet and it's been all over the world. But it's an art, not a game that exists in our spaces. It's currently in my garage under a tarp, but it's been everywhere. It sits in galleries, and it's an arcade game. It's built in Pico, and it's got a joystick, clicky buttons, and neon lights. When you play it, you are confronted with about 14 micro games that push you through my experience of being involved in the attack and losing my brother and going through all this stuff. It’s relentless. It finishes in four minutes, and then then it's done.

The reason that I liked that form was that a lot of the criticism I got for my early text work from those people was, “this isn't even a game, you can't win or lose this. This is bullshit.” So, I made the most ‘gamey’ game possible. And even people who are not running games will understand what you do in front of an arcade cabinet - you press buttons, you fire lasers, and you're done. And what this did was it fired a story quite aggressively over a few minutes.

To learn more about Closed Hands, including how to play it, visit its website.