Without The Legend of Zelda, there would be no Breath of the Wild. This may sound self-evident, but it is true in more ways than one. Not only did The Legend of Zelda give birth to the series of the same name, but the prototype which demonstrated the concept of Breath of the Wild was produced in the style of the original. It showcased the main ideas behind the new game, but it also showed that the 8-bit classic was timeless and adaptable.

Almost exactly thirty years ago, The Legend of Zelda debuted on North American soil. The exact date has mostly been lost to time (games would launch at different dates depending on the city and on capricious distribution networks back in the days), but most sources agree that it was somewhere between late July and late August. With the series reaching such a milestone, we decided to do something which is a favourite hobby of many gamers: reminisce!

Countless words and articles have been written about The Legend of Zelda. Its influence has been demonstrated, and its brilliance has been picked apart, so we will try to go in a different direction: Are there any secrets still hiding in the classic golden cartridge? Is there anything left to learn about this true NES masterpiece?

We think so, and we hope you will enjoy these fifteen crazy facts about the one that started it all.

15 The Game’s Title Make A Lot More Sense In Japanese

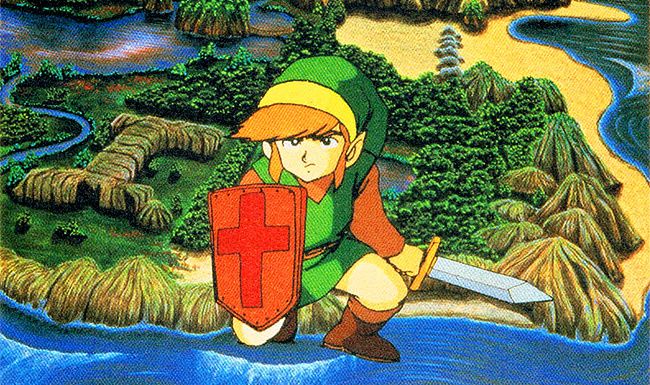

With a title like The Legend of Zelda, it’s a given that many first timers and people with only a casual awareness of the series will assume that “Zelda” is the name of its green-clad main character. It makes sense as the overarching title of the series, with subtitles defining every sequel, but it was quite confusing for the standalone first game. That is because the title was completely different in Japanese. A better translation would have been “The Hyrule Fantasy: The Legend of Zelda,” but Nintendo of America obviously thought that it was too wordy.

Funnily enough, because the series became so popular in North America and Europe, Nintendo eventually phased out the “Hyrule Fantasy” part to focus solely on “The Legend of Zelda.” The series now bears the same household name all over the world.

14 It Borrows From Another Nintendo Classic

What few people know is that The Legend of Zelda was developed more or less at the same time as Super Mario Bros., another legendary NES game. Shigeru Miyamoto has stated that he would often come up with an idea before deciding which game it fit better. Because of that process, he would sometimes realize that some concepts could be adapted to fit both games. A minor example of this would be the fire bar sprite, which appears in both games. A better one would be the Piranha Plants, which served as an inspiration for one of Zelda’s bosses. Manhandla, the boss of the third level, is nothing more than four Piranha Plants glued together. The Japanese instruction manual even states the following about the boss: "A four-limbed, jumbo-sized Pakkun Flower." Of course, "Pakkun Flower" is the Japanese name for "Piranha Plant". The evidence was there all along; it was simply lost in translation.

13 Miyamoto Giveth And Miyamoto Taketh Away...

From the first screen, it’s obvious that Link’s quest is not going to be an easy one. He starts weaponless, and people who come into this game without previous knowledge of the series could easily miss the cave with the Old Man and the sword. Turns out that Link was supposed to start with the sword, and we have Miyamoto’s bad temper to thank for the change.

After the game went into testing, feedback came where players were complaining that the game was too difficult and confusing. Well, Miyamoto got a bit cranky and decided to take away the starting sword as punishment, and leave players defenseless. His logic? If the game was too challenging, then he wanted players to talk with each other and share info. With the way that the game’s secrets became currency in schoolyards around the world, it’s hard to argue with his logic.

12 User Created Content: Almost But Not Quite

Once Nintendo ditched the science-fiction idea, they got to work building The Legend of Zelda with its actual aesthetic, but it had not settled on exactly what kind of game they were making. Development started under the assumption that the game was going to be a dungeon maker, something which would have relied on the Famicom’s brand new Disk Drive to share dungeons between players. Effectively, this would have been a Zelda version of Super Mario Maker, but before Zelda was even a thing. After a while, the development team thought that their own dungeons were good enough, and decided to scrap the “do-it-yourself” concept altogether.

The idea might have been risky at the time, but now that The Legend of Zelda is a guaranteed best-seller, how about revisiting that dungeon-maker idea?

11 The Second Quest Was An Afterthought

Nintendo has a reputation for its meticulous attention to details. Every aspect of its worlds are fully realized, every item is there for a purpose. Developing such games takes a lot of planning and organization, which is why it is so surprising to learn that one of The Legend of Zelda’s defining feature was nothing more than an afterthought.

In the game, players can famously access a second quest by entering “ZELDA” as the file name, but that was only added near the end of the development cycle. After finishing the first quest, the developers realized that they had only used about half of the memory they had planned on using. Takashi Tezuka, who apparently does not like wasting, decided to basically double the length of the game just to fill every last bit of space on the cartridge. And that’s how one of gaming’s most famous secret started: with bad planning.

10 Post-Apocalyptic Before It Was Cool

The publication of Hyrule Historia finally exposed the official timeline of The Legend of Zelda to the world. Given that Nintendo develops Zelda games without thinking of its placement in the timeline, making every piece of the puzzle fit must have required some serious mental gymnastics. In what is probably just Nintendo stumbling into some fortunate retconning, the original game is now said to exist in the series’ “dark” timeline. The timeline exists because of an alternate reality where Ganon did defeat Link in Ocarina of Time, thus sending Hyrule into chaos and decay.

The explanation works well because it explains design decisions which were probably based on technical limitations: There isn’t a whole lot of people living in Hyrule, after all, and most of them live in caves. That also explains why most Zelda games include the famous Hyrule Castle, but not this one, as it was destroyed in Ganon’s apocalypse. Well played, Nintendo.

9 The Notorious Censorship Of Nintendo of America

Nintendo of America, especially in its early years, was famous for censoring its games before releasing them in North America. Some games, such as Devil World, never made it out of Japan because of it. That’s why the presence of the cross on Link’s shield and on the Book of Magic is peculiar: Surely, Nintendo of America would have caught on to that one, wouldn’t they?

The truth is, they did catch on to the presence of religious imagery in the game. However, by that time, it was too late to redesign the offending sprites, and Nintendo of Japan wasn’t too concerned about putting in the effort because they weren’t exactly convinced that the game was going to appeal to Western gamers anyway. NoA did manage to censor one little thing in the end: The Book of Magic, as it is known in English, was actually named “The Holy Bible” in Japan.

8 Hyrule… In Space?

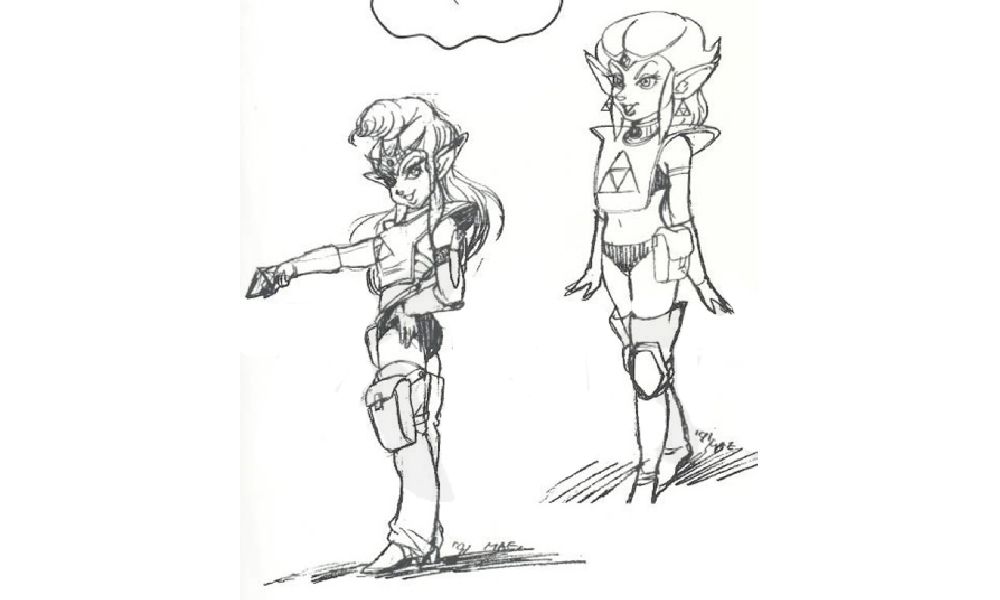

The Legend of Zelda may be famous for its fantasy setting, with swords and quests and elfish-looking creatures, but it was not always going to be like that. Early on in development, Nintendo had a completely different idea. Their game was going to take place in the future, and it was going to go heavy on science-fiction elements.

According to Shigeru Miyamoto, the game was originally about finding microchips instead of the Triforce. While the concept was eventually put aside, it was revisited when Nintendo was developing a sequel for SNES. Sketches were made, showing Link and Zelda in their space armor, but the idea was finally shelved in favour of what became A Link to the Past. While the image is certainly… interesting, it’s hard to argue with the final product in both cases.

7 The Famous Theme Was Also An Afterthought

Apparently, video games developers had a lot more slack to work with in the 80s. Before exposing the world to one of the finest pieces of 8-bit music ever written, Nintendo was going to use a famous classical piece, Ravel’s Bolero, as the theme. They surmised that the song was probably public domain because all classical music is, right? Eventually, someone did their homework and realized that not all classical music is that old: The Bolero was composed in the 1920s, which at the time of development was barely 60 years ago. That is below most of the world’s copyright cut-off, meaning that the song had not yet fallen into public domain. With the game almost ready to ship, Koji Kondo stepped in and came up with a quick replacement. Thankfully, it turns out that Kondo works well under pressure, and the theme he composed became arguably as famous as the game itself.

6 There’s A 16-Bit Remake, But You’ll Probably Never Play It

In the mid-90s, Nintendo released an add-on for the Super Famicom in Japan called the Satellaview. This add-on could receive games via satellite, which could only be played whenever they were broadcast on the device, similarly to a TV show. The most popular game on the service was BS Zelda no Densetsu, a spin-off based on The Legend of Zelda. It sported improved 16-bit graphics, and replaced Link with a character based on the player, but it was otherwise like the original.

The game streamed five times through the service, and then it was gone. Some fans preserved the game by hacking through their system’s memory to retrieve the data, but the fan-made emulations miss several of the original’s features, such as the voice acting that was streamed concurrently with the game. So unless you lived in Japan between 1995 and 1997, chances are you never have or will experience this game as intended.

5 The Japanese Version Had Voice-Activated Featured

Obsessive fans of The Legend of Zelda will remember that the instruction booklet mentioned an enemy called Pols Voice, a rabbit-eared creature which was described as hating loud noises. Yet, if one was to play the recorder (the only item specifically designed to make noise) in its presence, absolutely nothing special would happen.

This peculiarity was caused by a combination of translation issues and differences between the NES and Famicom. The Japanese console had a microphone integrated into its controller, and players in that version of the game were encouraged to yell into it to kill the Pols Voice. The NES version, of course, had no microphone, rendering that gameplay mechanic useless. It was taken out of the game, but obviously, no one thought it wise to notify the booklet’s translator.

4 Its Creators Are Credited Under Pseudonyms

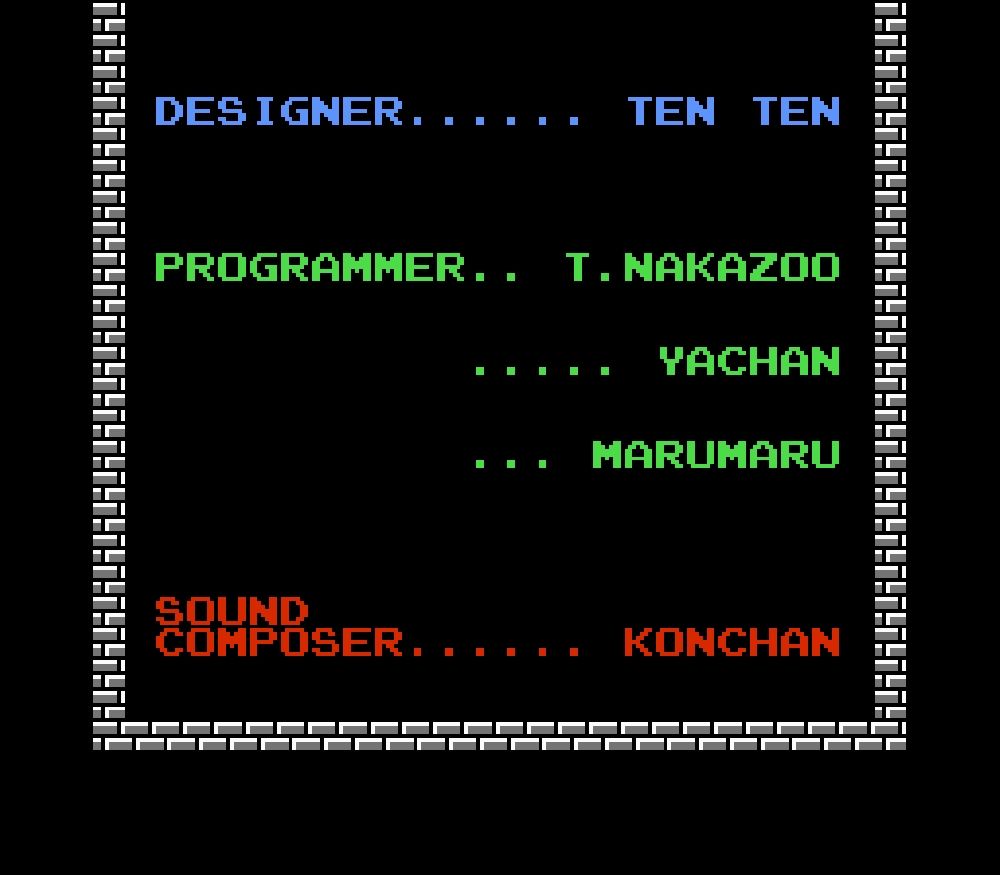

Gamers who make it through Ganon and all the way to the game’s credit might notice something strange. Except for Nintendo’s ex-president Hiroshi Yamauchi, none of the people usually associated with the game get a mention. There is no Shigeru Miyamoto, or Koji Kondo, or anyone else which history has shown us worked on The Legend of Zelda. That is because of an old mentality in the video games industry where companies believed that crediting the programmers and artists who worked on a game would lead to rival companies poaching their talents. In fact, most games did not even include credits at all for that reason, but Zelda was such a monumental achievement that the team wanted to show their work. They decided to do it under pseudonyms, with creative nicknames such as “Konchan” and “S. Miyahon” standing in for Koji Kondo and Shigeru Miyamoto.

3 It Was The First NES Game To Use Battery Backup For Saving

A game as massive (for its time) as The Legend of Zelda posed a problem: It was too long to be finished in a single session, and it was too complex to use a password system as was the norm in the 80s. In Japan, Nintendo solved that issue by releasing the game on the Famicom Disk System, which allowed saved games to be rewritten directly on the game’s disk. However, the Disk System was never released outside of Japan, so what can you do?

If you are Nintendo, you tame a technology previously reserved for personal computers and make your game the first home console product to include battery-backed RAM on the cartridge itself. This way, gamers could save their game before turning the system off, and the product could be left mostly intact. Because necessity is the mother of invention and all that.

2 It Was Almost Never Released Outside Of Japan

Japan must have a really bad opinion of Westerners and their gaming skills. After refusing to release the real Super Mario Bros. 2 (known as The Lost Levels elsewhere) in North America for fear that it was too difficult, Nintendo also waited 18 months after the Japanese release of The Legend of Zelda to introduce it to the rest of the world. The reason? Nintendo was convinced that Zelda would flop outside of Japan, as North Americans would not be interested in its slower pace, or in things that asked them to read a lot of text. After all, the trend at the time was that fast-paced, action-oriented arcade games were more popular. In the end, The Legend of Zelda sold two million copies in North America alone by the end of 1988, and the series has been consistently more popular on this side of the Pacific than in its native country.

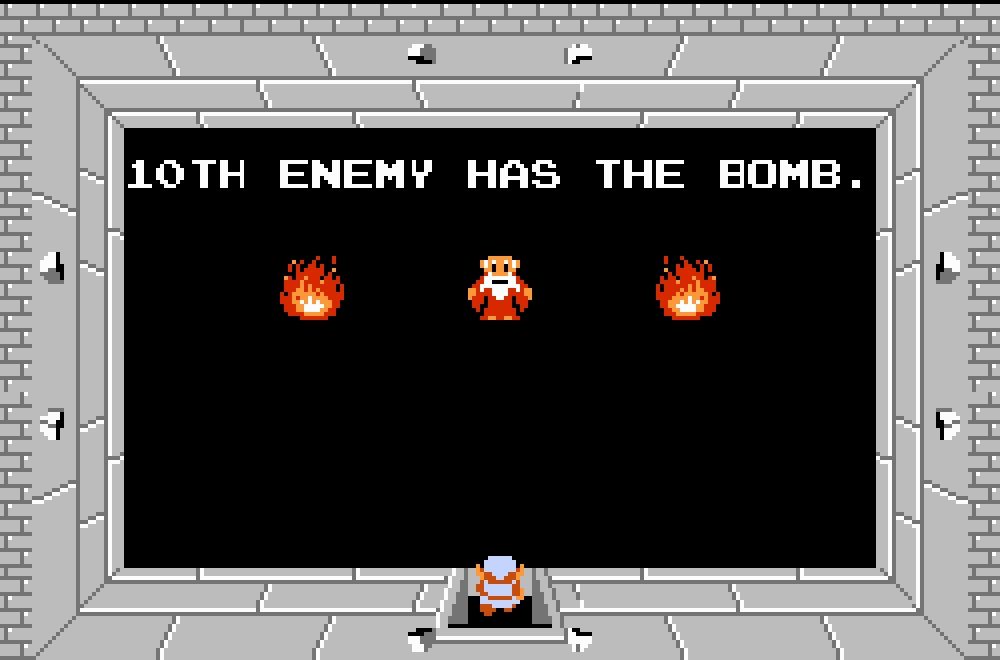

1 The Real Meaning Of “The 10th Enemy Has The Bomb”

The Legend of Zelda is full of examples of bad English and nonsensical hints. Of all these mistranslated and cryptic clues given by the Old Man, this one is the most misunderstood.

“10th enemy has the bomb.”

This clue went completely undeciphered for a very long time, and it wasn’t until the internet came to the rescue that its meaning was finally understood. As it turns out, it’s a tip that tells you how to get more bombs to drop: If you kill nine enemies without being hit, then defeat the tenth one using a bomb, that enemy will drop multiple bombs for you to add to your inventory. That trick works every time, but it’s hard to see how one could understand that from the single, obtuse sentence offered by a non-playable character. Even weirder: the original Japanese tip simply mentions that the Lion Key could be found in the current dungeon, so, hey, good job translator.