Cult of the Lamb may be the first cult-running simulator I’ve played, but it’s carrying on a proud video game tradition that I’ve seen in the medium for decades. Like The Witcher 3, Horizon Forbidden West, and Knights of the Old Republic before it, Cult of the Lamb has a distractingly good game within the game. This time around, it’s called Knucklebones, and I am determined to be the very best like no one ever was.

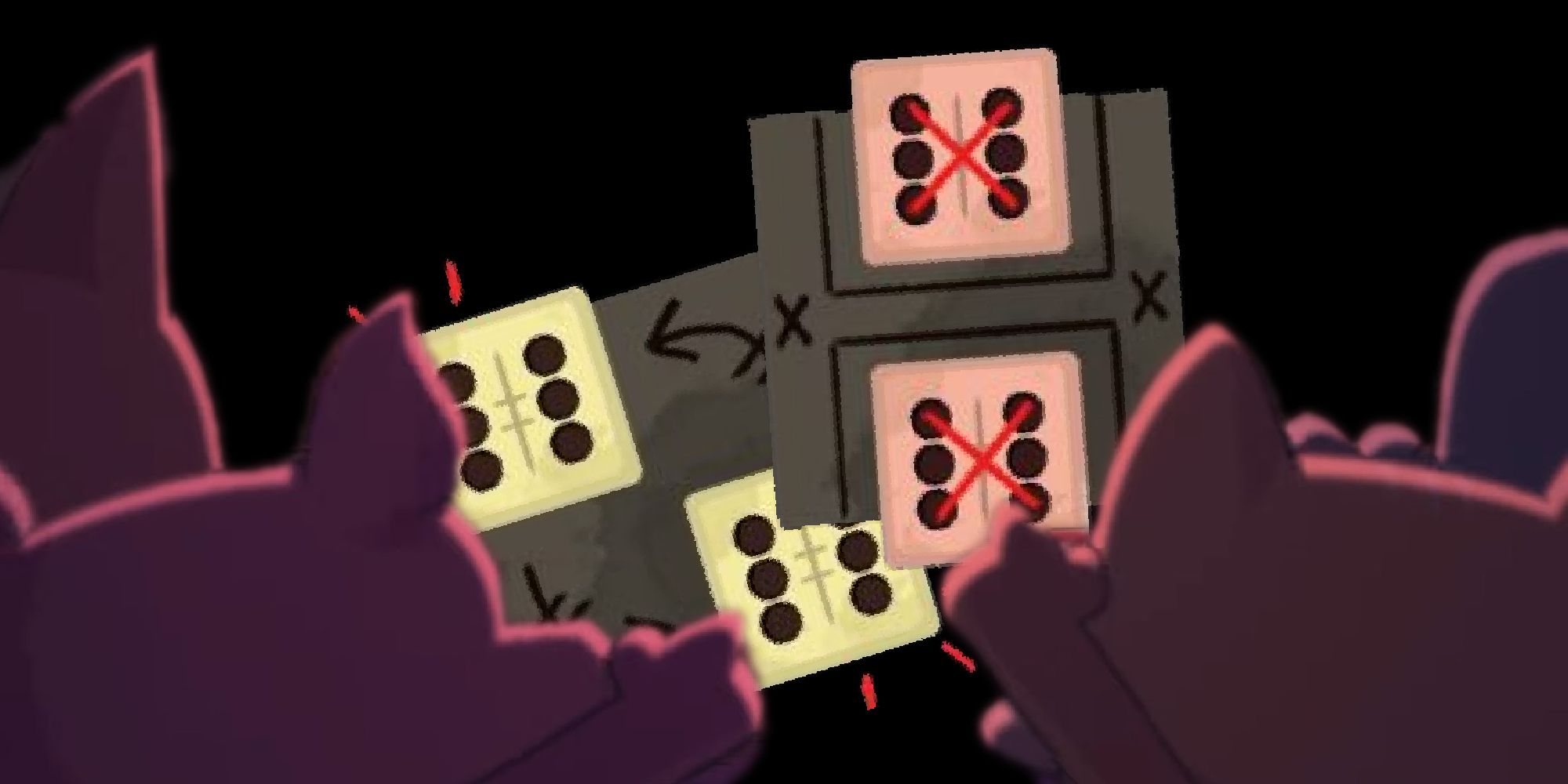

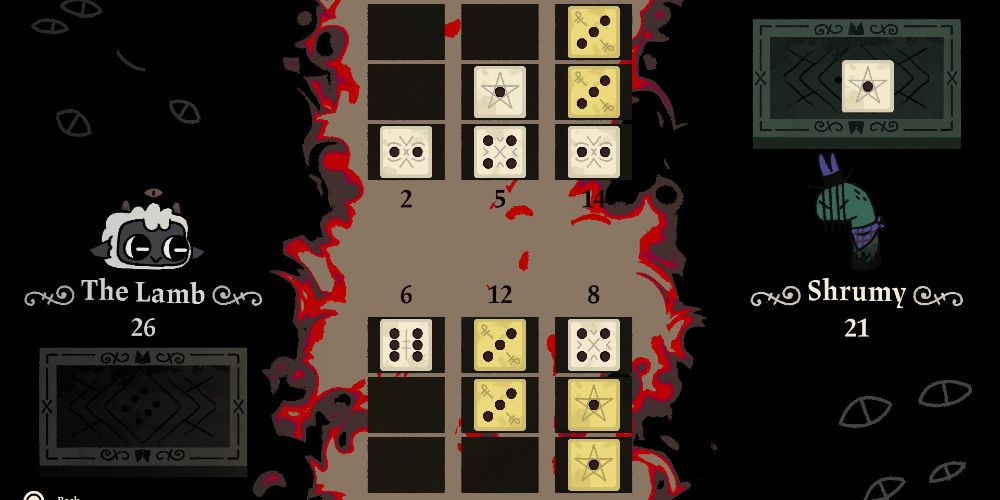

Knucklebones is simple enough. It’s the kind of game you could play in real life (provided you have easy access to 18 six-sided dice). Each player plays on a 3x3 grid which is divided into three columns. Each time you roll a die, you must place it into one of the columns. If you can line up two or three of the same number in a column, its worth multiplies exponentially. But, if your opponent plays a die of the same numerical value in the equivalent column on their side of the board, it will take out any matching ones on your side. This is annoying if you have one die with that number, but if you've built out a column with two or three, it's devastating to your score.

Your Knucklebones teacher and first — for me, so far, only — opponent is Ratau, an elderly former "chosen vessel" of the game's ancient, evil god who has been sent to guide your lamb on their path. Basically, he's an old retired rat who lives in a Lonely Shack to the north of your village, and will take any opportunity to play Knucklebones with you. Thankfully, given that cash can be difficult to come by in the early game, he also loves to bet on it.

Money brought me to Ratau's shack for a few games early on. But, as you get further into the game, the amount of scratch you can earn by besting Ratau stops being significant. And, more pressingly, your village exists in real-time so, while you're away from it, cult life goes on. Your cultists get hungry. Without consistent reinforcement of your cult’s supremacy, their zeal grows cold and, if it gets chilly enough, they’ll desert — or, at least, talk shit about your cult to their fellow members. In your absence, old members die and healthy members poop on the grass, causing other members to get sick. In short, heavy is the head that wears the crown. So, while the profit motive incentivized me to play the game early on, the fun of it is what keeps me coming back in the face of domestic responsibilities.

Side games often exert this kind of hold on me. In Stardew Valley, I found myself drawn, time and time again, to Journey of the Prairie King, the cowboy twin-stick shooter found on an arcade machine in The Stardrop Saloon. Though I found Horizon Forbidden West frustrating in many ways, I had no complaints about Machine Strike, the tactical board game Aloy can play with the denizens of the post-apocalypse. The only time I've played Wolfenstein 3D to completion was on the arcade cabinet aboard Eva's Hammer in The New Colossus. Even when a side game is simple, like the solitaire included on Telling Lies' in-game desktop interface, I find it a welcome respite from the main game. Gwent being popular enough with Witcher 3 players for CD Projekt Red to spin it off as a standalone game suggests I'm far from alone.

Cult of the Lamb is a significantly deeper experience than the dice game it contains, with so much mechanical depth, I'm amazed it feels easy to pick up and play. That complexity may explain Knucklebones' allure. In the midst of the tangled web woven by anyone attempting to run a religion, I can find solitude in a lonely shack; order in the simple process of arranging dice in columns with an old rat.