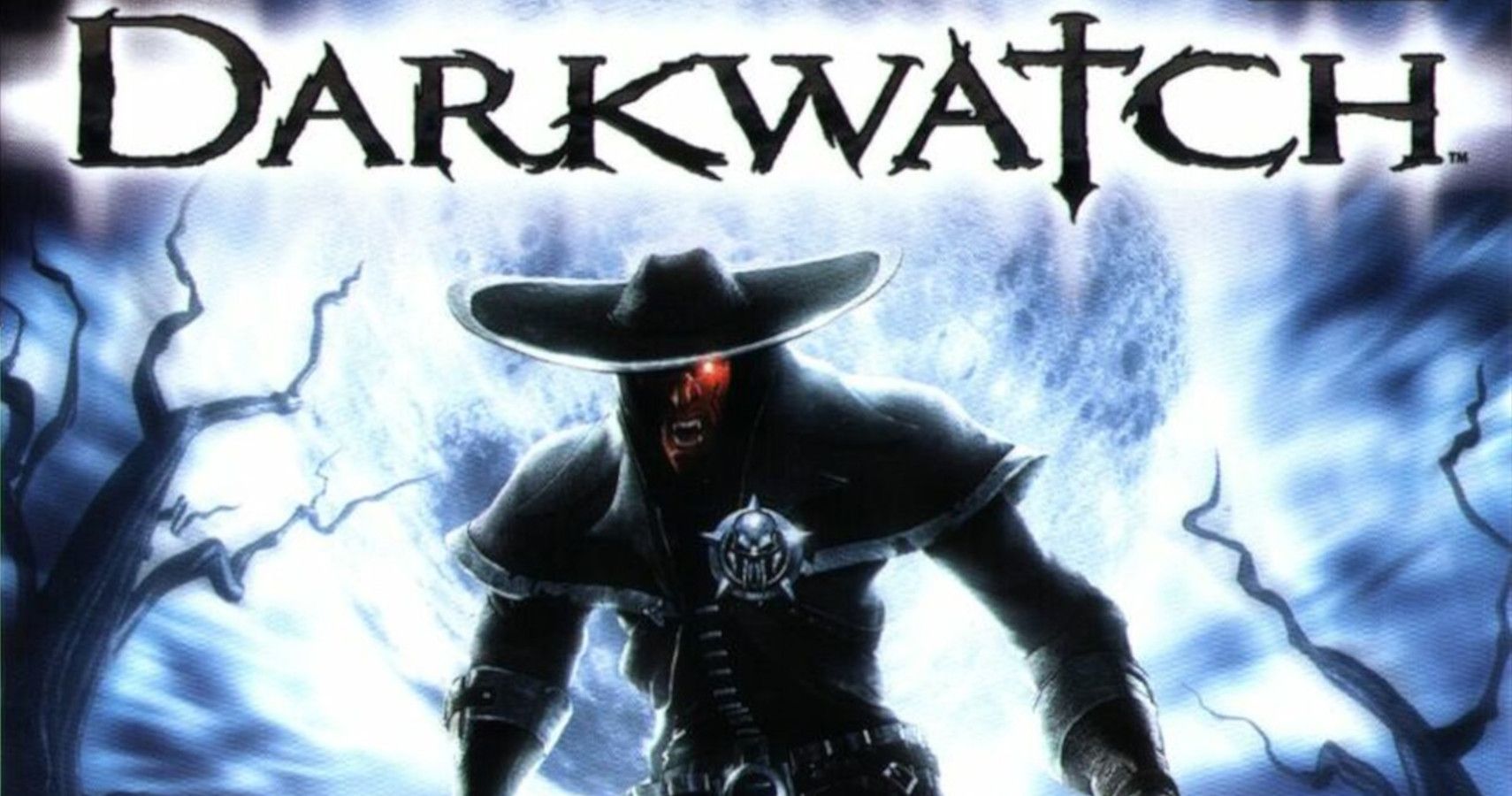

It’s been 15 years since the release of Darkwatch, but creators of the game have never stopped dreaming about what the universe could have become. “I miss Darkwatch every day of my life,” Darkwatch lead designer Paul O’Connor tells me. “That was our company, that was our game, that was our shot.”

O’Connor is one of the four co-creators of Darkwatch and a founding member of both Sammy Studios and the company it would eventually become: High Moon Studios. O’Connor, along with Chris Ulm, Farzad Varahramyan, and Emmanuel Valdez, brought Darkwatch to life amidst years of organizational changes and economic uncertainty. Between the development of Darkwatch and its ill-fated sequel, ownership of the studio changed hands five times before eventually becoming a subsidiary of Activision Blizzard, where it remains to this day. Despite a positive critical reaction to Darkwatch and an enthusiastic fan base, Darkwatch 2 became a casualty of conflicting business directions, and the series never became what its creators hoped it could be. “We know it wasn’t perfect,” O’Connor says, “but we also think that we were onto something, and it’s a crying shame that it didn’t become a franchise.”

Code Of The West

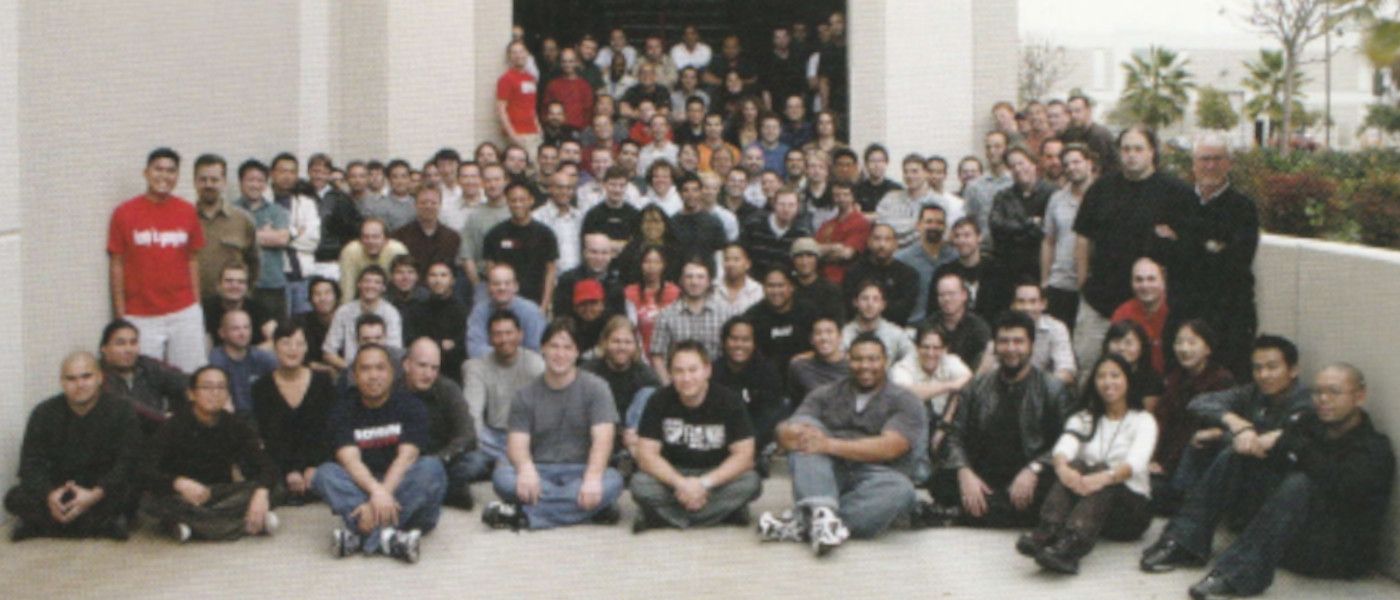

In 2002, the Japanese company Sammy Corporation hired Midway’s former vice chairman, John Rowe, to lead a brand new development studio in Carlsbad, California. Sammy Corporation previously had some success developing arcade games like Viewpoint and Survival Arts in the 1980s, but had largely abandoned game development to focus on its highly profitable pachinko machines. With Sammy Studios, the company was hoping to break into the western market in a big way. “Sammy was a big swing,” O’Connor explains. “We hired in a hurry, and we got big.” The 30,000 square foot custom facility could accommodate development on multiple games and included a publishing arm that would localize Japanese games and seek out original titles in Europe and North America to publish under Sammy Studios. Chris Ulm, Darkwatch’s design director and co-writer, estimates that, at its peak, Sammy grew to around 200 employees. “We were going in a lot of direction at once,” O’Connor recalls.

Rowe hired creative director Emmanuel Valdez, whom he’d previously worked with at Midway, while the other three co-creators, O’Connor, Ulm, and creative visual director Farzad Varahramyan, had all previously worked together on the Oddworld series. Early on, Valdez and Varahramyan explored a number of licenses on older games owned by Sammy, including a potential remake of Ecco the Dolphin, but the team was keen to focus on development of an original IP. Ulm was a former editor-in-chief at Malibu comics and had helped launch original IPs like The Ultraverse and Men in Black. “Men in Black was a 5,000 circulation comic book that ended up becoming a major international franchise,” Ulm explains. “If you create a character in a world, that world should have franchise potential to become a board game, an animated show, or a movie.” In the summer of 2002, Sammy Studios got the green light to develop two original IPs: a sci-fi shooter called Invasion L.A., and a western called Code of the West.

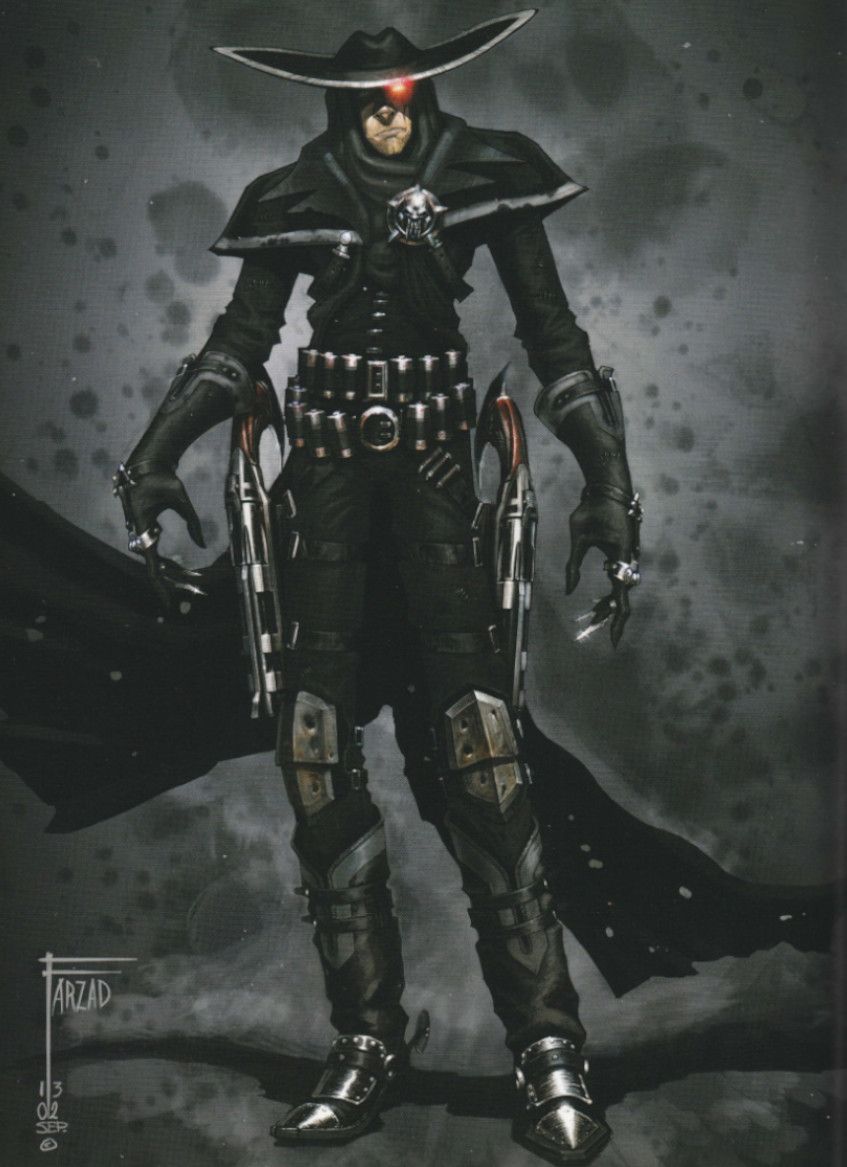

Code of the West had very little in common with Darkwatch, the game it eventually became. The original concept featured a protagonist named Chaz Bartlett, a ne’er-do-well gambler who “was always one step ahead of the law, stealing a horse to get out of town with his ill-gotten gains,” as O’Connor describes him. The character went through a number of iterations, often resembling Sheriff Woody from Toy Story. At one point in development, Chaz became a New York watchmaker with a monkey sidekick. As most of the co-creators had come from Oddworld, they were interested in trying something more light-hearted and comedic, but over time, it became clear that Code of the West wasn’t a good fit for a first-person shooter. “We had a moment internally where Chris Ulm looked at it and said ‘Think about our player, are they gonna want to be that guy? And the answer is no,” O’Connor says. “So with that in mind, we disrupted ourselves and Farzad went back to the drawing board and developed the character that became Jericho Cross.”

The world of Darkwatch evolved quickly from there. Rowe pitched the new direction to Sammy Japan and was able to secure the company’s blessing, and with the new direction solidified, Varahramyan started producing incredible concept art that inspired the entire team. “The work [the concept] uncorked from Farzad was just brilliant,” O’Connor explains. “He had this Renaissance-like explosion where we got Jericho, we got the steam wagon, and we got all these crazy enemies. The world just started to flow from his pen. It was clearly telling us that that’s the game it needed to be.”

By combining elements of gothic horror with western motifs, the team believed that they had found a visual identity for Darkwatch that they could own. The Haunted West genre had not yet been explored in video games, and as a vampire cowboy, the team discovered that Jericho made an ideal first-person shooter protagonist. Jericho’s powers, like the blood shield and vampire jump, opened the door to thrilling, fast-paced combat and interesting level design. The Darkwatch organization drew inspiration from the high-tech secret society in Men in Black, and the story included characters and themes inspired by comics. All of the pieces were falling into place creatively and the team was making significant progress on Darkwatch. Unbeknownst to them, a major shift at Sammy Japan was about to put the future of the studio in jeopardy.

High Moon Studios

In 2003 Sammy Corporation purchased a controlling share in Sega from Sega’s former parent company, CSK. The founder of CSK and the chairman of Sega, Isao Okawa, died of heart failure in 2001. Okawa had a close personal relationship with Hajime Satomi, CEO of Sammy Corporation, and before his death, had expressed to Satomi that he was concerned about the fate of his company. Sotomi agreed to take it over, and in mid-2004, Sammy and Sega merged, forming a new company, Sega Sammy Holdings.

Following the merger, Sega was put in charge of Sammy Studios. At the time, the team was enthusiastic about joining Sega. “We thought ‘Hey yeah! People know Sega more than Sammy, that’s a great alliance!’” Valdez recalls. “We thought maybe something great will come out of it.” Unfortunately, this left the Darkwatch studio in a precarious position.

“Right in the middle of our development, we suddenly were spliced together with Sega,” O’Connor remembers. “They came down and kicked the tires on our studio and basically said ‘Why don’t you guys wrap up Darkwatch, and then we’re going to close the studio, because we don’t need any of the things that you do.’” All of the personnel and infrastructure that Sammy had built up to become a presence in the west was now redundant under Sega. The company had no use for Sammy Studios’ fledgling publishing arm, mocap studio, or development team, and decided to shut the studio down following the release of Darkwatch. “I don’t know if they viewed us as a threat, or if that was just their hard-hearted assessment about our redundancy,” O’Connor says. “But now in the wake of a merger, there was going to be a consolidation of costs.”

With more than 200 jobs on the line and the future of Darkwatch at stake, John Rowe went to Japan to appeal to Sotomi in person. “He said, ‘Sotomi-San you can’t do this,’” O’Connor explains. “‘It’s on your reputation, the promise you made to these developers, people uprooted their lives, they moved to Southern California, they’ve gotten married, they started families. They’re deeply invested in this game. You can’t take it away from them. It’s not fair.’ And so Sotomi-San, being an honorable man, agreed.” Rowe was able to purchase the studio from Sammy Sega with a small group of partners. Together they founded High Moon Studios (named after a piece of concept art of Jericho, drawn by Varahramyan) and development of Darkwatch continued.

Of course, taking the company private had major consequences. As O’Connor puts it, “Suddenly, our burn rate was our burn rate, we weren't spending Japanese money anymore to keep the studio open.” Downsizing was inevitable. Invasion L.A. was canceled, the publishing arm was shut down, along with marketing, QA, and sales. A number of developers were laid off. “That was the saddest day we ever had at High Moon,” O’Connor remembers.

High Moon had a number of immediate problems to solve. Without Sammy and the publishing arm, Darkwatch would need to find a new publisher. The studio wouldn’t be able to recoup development costs until the game was released, so in order to stay in business, they would need to seek out financing. High Moon opened the door to work-for-hire opportunities and quickly struck up a deal with Vivendi.

Following the success of the first two Jason Bourne movies, Vivendi purchased the rights to develop games based on Robert Ludlum’s novels. The company was interested in building up its own version of Ubisoft’s Tom Clancy franchise, and so hired High Moon to develop a game called Robert Ludlum’s The Bourne Conspiracy. The studio split development, with Valdez and Ulm moving over to direct Bourne while the rest of the team finished up work on Darkwatch.

Despite the work that High Moon was doing on Bourne, Vivendi wasn’t interested in publishing Darkwatch. “The Vivendi people were always very jealous of our development bandwidth,” O’Connor explains. “It’s like ‘Well, are we getting your best people? Are you on our project or that project? You own this one, and this one you’re just work-for-hire.’” Vivendi had multiple Robert Ludlum games in development at other studios, and Bourne was their main priority. Darkwatch was very close to being completed, but it still didn’t have a publisher.

Just three months before the release of Darkwatch, High Moon managed to find a pair of publishers for the game: Capcom in North America and Ubisoft internationally. Darkwatch ended up with a decent budget for marketing, which included TV spots and a presence at E3, but because neither company owned the rights to Darkwatch, neither had the incentive to promote or further develop the Darkwatch IP after release. “It was like, ‘We’re going to ship the game this quarter, we’re going to make our money, and we’re going to move forward.’” O’Connor recalls.

Darkwatch had a handful of eye-catching marketing campaigns, including a music video featuring Good Charlotte’s song Predictable and several nude photos of the game’s female protagonists, Tala and Cassidy, featured in Playboy. The spread was controversial among the creators, but it did have an effect, as O’Connor describes it, of “cutting through the noise.”

“There was some real heat on Darkwatch at one point,” Varahramyan says. The creators started taking meetings with film producers and movie studios about a possible live adaptation of Darkwatch. Paul W.S. Anderson, the director of the Resident Evil film series, made an offer on Darkwatch. Valdez recalls Focus Home optioning the rights to Darkwatch as well, while the creators also took meetings with Jan de Bont, Roger Avery, Glen Morgan, and James Wong.

Ultimately, any opportunities to develop Darkwatch outside of games had to be put on hold as High Moon studio entered negotiations to be acquired by Vivendi. At the time, the developers feared that selling off any of the rights to Darkwatch might have diminished the value of the company. Though Bourne was still in development, Vivendi believed in the Robert Ludlum IP and wanted to see High Moon continue development on the series for multiple installments. The Darkwatch creators, of course, had other priorities. “If I had a time machine, I’d go back to the negotiating group and say, ‘Carve out Darkwatch,’” O’Connor said. “They weren’t really interested in it, just set it aside, own it, set up a separate company for it.” With the imminent release of Darkwatch and the future of High Moon uncertain, Vivendi acquired High Moon Studios, and Darkwatch, in January 2006. After the release of Darkwatch, the entire studio then pivoted to work on The Bourne Conspiracy. When Bourne shipped in mid-2008, High Moon got to work on two new games: a sequel to Bourne, and Darkwatch 2.

Darkwatch Through The Ages

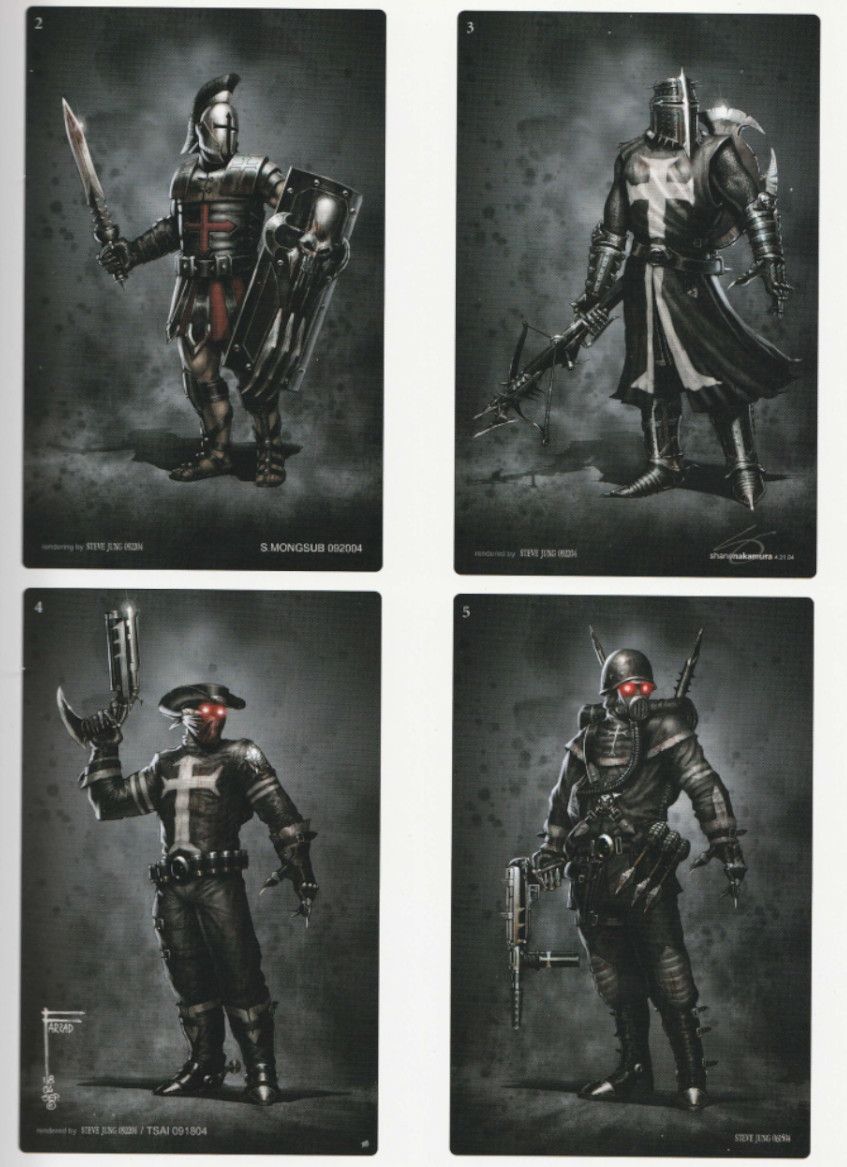

In the lore, the Darkwatch was a secret organization created during the Roman Empire to fight the forces of evil and undead. From the earliest stages of development, the creators conceptualized a “Darkwatch Through the Ages.” They believed that they had unlimited potential to tell Darkwatch stories by exploring the history of the organization during different time periods, not unlike what the Assassin’s Creed franchise became just a few years later. For Darkwatch 2, the developers decided that it was time to leave the old west behind and take Jericho to the far future.

“Darkwatch 2 was going to be a post-holocaust story,” O’Connor explains. “It was going to be the vampire Holocaust.” In the future, Darkwatch had failed to protect the world, and the vampires were now keeping humans on reservations where they could be hunted for sport. After discovering a young girl whose blood was poisonous to vampires, the scattered remnants of Darkwatch seek out the tomb of Jericho Cross and manage to resurrect him. O’Connor compares the story to Mad Max, because of the relationship that develops between Jericho and the girl.

Darkwatch 2 was being developed in Unreal, unlike the original, which used a proprietary engine. The developers decided to move the perspective from first to third-person for the sequel because they found that they could make more tactical and frenzied combat with the increased situational awareness that third-person provides. Varahramyan redesigned Jericho, removing his hat so that his face was easier to see. Gameplay-wise, the emphasis for the sequel would have been on big, cinematic boss fights. The team put together a playable demo that showed off Jericho’s new powers and animations. “It was more visceral and more immersive than Darkwatch was,” O’Connor remembers.

“We had a team that had learned so much,” Ulm adds. “We were ready to expand the things that we thought were really working well.” One of the things the team was excited about exploring in the sequel was multiplayer. While both versions of the original game included a co-op mode for the campaign, the competitive multiplayer mode in Darkwatch was exclusive to the Xbox, and it came together late in development. Now that the Xbox 360 and PS3 offered a more evolved online infrastructure, the team intended to focus on multiplayer as a core feature in Darkwatch 2. “We wanted to figure out how our systems would translate to a multiplayer-centric game,” Ulm explains. “We were moving the game to be more about you and your friends playing together.”

The team was making major progress on Darkwatch 2, but in 2007, everything changed for High Moon once again. “We were all kind of sensing something was going on,” O’Connor remembers. “Our executive leadership was a little AWOL.” Vivendi had gone dark on High Moon, leaving them to work on Darkwatch 2 and Bourne 2 in relative isolation. Unbeknownst to High Moon, Vivendi had entered into negotiations with Activision to form a merger. The parent company became Activision Blizzard in December 2007, and Activision immediately took control of High Moon Studios. Unfortunately for the Darkwatch team, Activision wasn’t interested in continuing development on the sequel.

By 2007, Activision had established itself as the “wise custodians of brands,” as O’Connor puts it, with major franchises like Guitar Hero, Tony Hawk, and Call of Duty. Activision had a certain way of doing business, and building up new IPs wasn’t part of its plan.

“I had this conversation with them when they came in,” O’Connor remembers. “We were having our meet across the dinner table thing, and I said ‘You know what we do really well here at High Moon? We make new stuff. Isn’t that going to be great for you?’ And they’re like, ‘No, we don’t do that. What we would rather do is overpay for the one IP that works, rather than plant 1,000 flowers and hope to grow one at home.’” At the time, Activision didn’t invest in new IPs, it bought existing IPs. “You can’t dispute their business acumen,” O’Connor admits. “But it ended up being a really bad cultural fit, given what we were doing.”

Buried In The Tomb Of Jericho Cross

Activision’s people came to High Moon Studios where the developers showed them the work they were doing on Bourne 2 and Darkwatch 2, but as expected, Activision immediately ended both projects. “They said, ‘That’s awesome work, we love the potential and the talent of the studio,’” O’Connor says, “‘Now get started on Transformers.’” High Moon immediately pivoted to development on Transformers: War for Cybertron and the four co-creators of Darkwatch resigned the same day.

The Darkwatch co-creators stayed together for many years and formed a mobile game company called Appy, while High Moon continued on, developing a total of three Transformers games, followed by Deadpool, and has since transitioned to an insourcing and support studio, first for Destiny, and now for the Call of Duty series. Despite its beginnings as a studio that believed strongly in the value of creating and owning its own IPs, Darkwatch was the only original IP that High Moon Studios has ever created.

In the years since leaving the company, Activision has never reached out to the Darkwatch creators about continuing the series. At one point, the original creators did try to acquire the rights, but negotiations didn’t get very far. “We heard from a friend of a friend that maybe we could go get that IP,” O’Connor says. “There were some very informal discussions, but the price was too high for us, we just couldn’t afford it.”

In 2017, O’Connor was working at Capcom Vancouver on an unannounced game codenamed Panther. The studio was exploring ways to revitalize Darkwatch before discovering that, though Capcom had published the original, it did not own the rights. O’Connor believed it may have been possible to acquire the Darkwatch rights from Activision with Capcom’s backing, but Panther was canceled after the studio suffered major layoffs in February 2018, and O’Connor left the company.

All four of the Darkwatch creators tell me that, given the opportunity, they would all come back to Darkwatch. “I want Darkwatch to come back,” Valdez says. “I’ve never discounted a game like that to be resurrected, as long as fans keep it alive and in people’s memory.”

“I have a giant soft spot in my heart for Darkwatch,” Ulm admits. “There hasn’t really been another game that makes you feel that way, in my opinion.

“If I could get the band back together,” O’Connor adds. “We’d make another game. I’d want to do it with the people that did the last one, as many of them that would want to come along. I think there might still be stories to tell in the Haunted West.”