Today, news came that Nintendo would be releasing the original Fire Emblem game in English for the first time. However, there's a catch - the game, both in its digital and physical release, will be available for a limited time only.

This comes mere months after Nintendo put out Super Mario 3D All-Stars - a truly bad compilation that's nevertheless a timed release. Once the copies dry up, and once Nintendo hits the arbitrary date they've set, the collection will be pulled. So, too, will Super Mario 35, a cheeky little battle royale spin on the classic Super Mario Bros.

Why, though? What's the point to any of this? Would Nintendo not benefit from having the games out at all times? And for that matter, why aren't more Nintendo classics more readily available anyway? To understand this, we'll need to jump back a few decades.

The Most Magical Copyrights On Earth

In the '80s, home video was on the rise. More and more film companies rushed to mine their archives for anything they could slap on VHS, as the format became a ubiquitous presence on store shelves. However, one company was holding out: Disney.

You see, Disney had long opposed home video releases of their films. The company made so much money from theatrical re-releases that they saw widespread accessibility to their product as a threat. They'd stymied attempted television screenings of their animated classics several times in the past, even as their peers were embracing the format. And when VHS started to rise up as a viable format, Disney even tried to sue Sony into discontinuing manufacturing them.

That's right - Disney tried to singlehandedly destroy home video as we know it today. You can learn more about that story here.

They failed, of course. VHS was here to stay, and the company had to deal with it - as much as their executive board didn't want to. Oft-maligned CEO Ron Miller pushed against this mentality and tried to bring the company's classics to VHS, only to be met with resistance and an eventual ousting from the company. It was only until the innovative, yet controversial Michael Eisner came aboard that the company would make its first forays onto home video in earnest.

It came with a catch, though. Early VHS releases of Disney films were ludicrously overpriced - a deliberate tactic that encouraged video stores to snatch these tapes up, but made them fairly inaccessible to average consumers. On top of that, these were extremely limited releases, something that the marketing made crystal clear. Customers only had a certain amount of time to snatch these up before they went back in "the Vault" - an ambiguous void where Disney threw their movies until they wanted to make money off them again.

(Yes, I know the vault is a real place. Shush.)

This practice persisted for decades, with special editions of beloved classics popping up, selling out, going out of print, and becoming scarce collector's items. At its heart, this practice is deeply anti-consumer - it encourages blind brand loyalty and an itchy trigger finger to spend money, and it makes physical copies of Disney films into a valuable commodity they have no right being. Still, it was an effective marketing tool, and despite its official retirement, Disney is still utilizing the system - especially with their 20th Century Fox catalog.

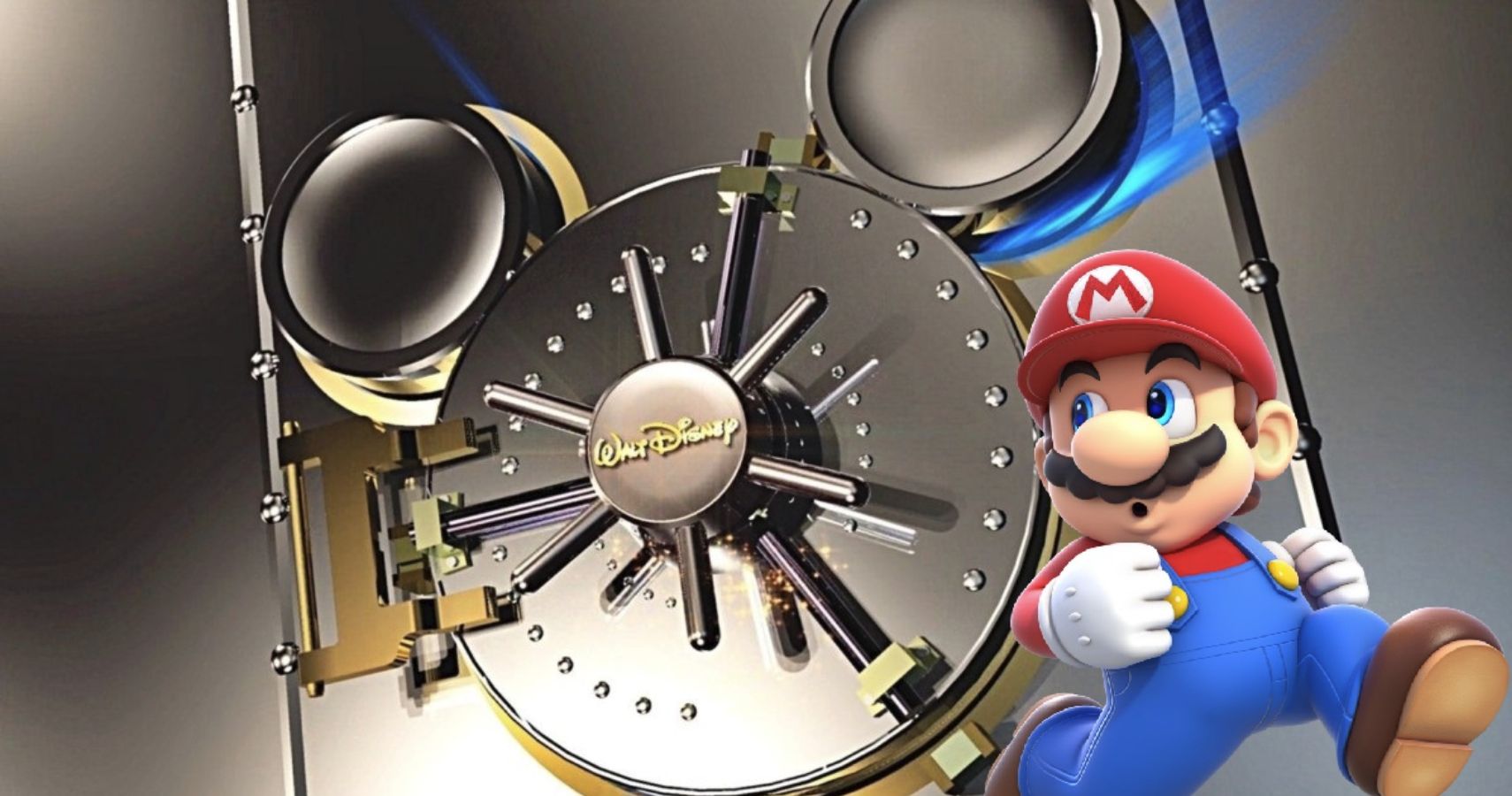

But today, Disney is far from the only company doing this sort of thing. With the popularity and notoriety of their Vault system, the House of Mouse sketched a handy blueprint for one of the most anti-consumer enterprises today: the gaming industry. Many big-budget video game companies thrive on artificial scarcity, premium prices, and restrictive control over what a consumer can or can't do with their product.

And when it comes to these restrictive, confusing practices, no company does it quite like Nintendo.

"Super" Bad For Consumers

Everything about the Big N, from top to bottom, is built around a tight and restrictive control of their IPs and everything affiliated with them. In the company's early home console days, they would sue the living daylights out anyone who dared to make cartridges for their platform. During the advent of the Genesis, they would punish retailers that stocked the competition. When working with Sony, they stabbed the company in the back after a squabble over proprietary tech. This is a company that's always been about one thing: control. Control over their technology, their IPs, and, in the early days, the entire video game industry.

But just because Nintendo's initial monopolistic aspirations didn't pan out doesn't mean that the practices informed by them went away. To this day, Nintendo games still remain priced at a premium - rarely going on sale or dropping in price. Their products, from the SNES Classic to the first few years' worth of Amiibo, are produced in limited quantities and quickly marked up to absurd prices after-market - driving demand until Nintendo floods the market and cheapens their value. Despite their cuddly, family-friendly brand image, Nintendo is as cutthroat and restrictive as they've ever been.

You can also see this in how they refuse to make their older games readily available. And it is a matter of refusing - we know Nintendo can do this, in certain cases. When Nintendo apologized for slashing the price of the 3DS by eighty bucks five months after release, it offered up ten NES games and ten GBA games for early adopters - along with a piss-yellow certificate. These GBA games all ran fine on the system, and people naturally assumed it was a sneak peek of what was to come.

Only... it wasn't. Nintendo didn't ever put any other GBA games on the platform, despite the fact that they can run natively on the hardware. Just like they didn't translate the Wii's robust Virtual Console to any future systems, forcing players to rebuy games they already paid for. Just like the Switch shipped with an NES emulator, but waited over a year to make certain games available through a paid subscription service that you need to go online once a week to play.

(Oh, and don't get me started on their treatment of fan projects, or their restrictive approaches to streaming. We'd be here all day.)

As a company, Nintendo is one of the most egregious anti-consumer enterprises out there. Their interests are entirely self-serving, and it's only through a cute, cuddly veneer (not to mention undeniably fantastic games) that they've managed to deflect years of justified criticism.

The Nintendo Vault?

Which brings us back to the present. Nintendo seems pretty dead-set on this "new" approach to releasing their classics - put them out for a little while, let the hype build, then yank them away before that enthusiasm can ever stagnate. From a consumer point of view, this makes IPs seem more precious, and therefore gives more perceived value to them. But this is a trick and a trap - an insidious method of IP control that Disney perfected decades ago, and that Nintendo is now implementing during around the same period in their cycle.

In my mind, that's no accident. Nintendo has long since been compared to Disney in the press, and numerous luminaries in the company have drawn direct parallels between their products and Disney's. To me, it's not too much of a logical leap to say, at this point in their history, Nintendo is looking to the company for inspiration on how to maintain their IPs for years and years to come.

In Disney's case, the vault system worked. It made their brand feel special during uncertain times for the company, and helped maintain their image while they figured out how to steer the ship after Walt Disney's passing. Today, they're one of the largest companies in the world - a seemingly unassailable testament to unchecked capitalism.

But how will this pan out for Nintendo? Only time will tell. More so than film, video games are a fickle medium with an even more fickle audience. In the historical sense, we're still in the relative infancy of the medium, which makes it impossible to gauge whether or not this bold strategy will pay off for the Big N.

And yet, there is that historical precedent - that shining example of a family-oriented company so fiercely protective of their brand that they'll rewrite copyright laws to protect it. There's a playbook for Nintendo to draw from, and it's one that goes back decades.

Mario, meet Mouse. I think you'll get along.