Pop quiz: what does almost every marquee Ubisoft game since 2012 have in common?

Answer: they're all the same fucking game.

The player gets a big map, most of which is covered up, and is given places to go "liberate" to unlock more of said map. As the player discovers more map, they organically stumble upon side missions that range from "easy" to "controller is in chunks on the floor." Then the story missions get harder, and you're forced to do the side missions - but only certain ones, because other ones are literally impossible. More often than not, you find yourself banging your head up against the wall until you eke out a victory, or you pay Ubisoft some sweet microtransaction bucks. Then you level up, slap some points into a skill tree, and keep on truckin'.

All the while, the game spoonfeeds you a narrative that's topical, but toothless. Sure, it references current events, or hints at profundity, but ultimately the game's narrative leaves you unchallenged and unchanged in your worldview. This goes for games that I like, too, like Watch Dogs 2 and Ghost Recon Wildlands - titles that double down on current world conflicts, but sanitize them to an offensive degree. The former title seems to have a lot to say about racial inequality, but actually just serves to reinforce the status quo; the latter shows the devastation wrought on Bolivia due to a drug war, only to ultimately justify the destructive presence of the US government. By both games' ends, nothing changes - especially not the player.

But while it would be tempting to trace this back to Ubisoft's Assassin's Creed franchise, it actually takes root in their other big cash cow: Far Cry, a series that peddles in broad stereotypes, contrived progression, and shapeless, formless gameplay gussied up by cool guns.

Play By The Rules

Let's stick with the mechanical side of things for a second, because we're already here.

While modern Ubisoft structure can be traced back to the early Assassin's Creed titles, or even Far Cry 2, I think most would agree that it takes root in Far Cry 3. The 2012 video game blew the door wide open in terms of open world game progression, and really finalized the blueprint of AAA gaming for the next decade.

Incremental map unlocks tied to numbers going up? Check.

Sandbox gameplay that encourages you to "play your way," while actually forcing you to "play one of these two or three ways"? Double check.

Morally grey story with shocking subject matter that doesn't serve a real purpose, other than making you say, "wow, they sure went there"? Check, check, and check, baby.

In retrospect, it's very easy to see how deliberate and insidious Far Cry 3's design is. Every aspect of it feels tailormade for rinsing and repeating, from the skill trees you use to gradually unlock vital mechanics, to the large map of distractions that you're strongly encouraged to unlock in a certain way, to the hybrid of stealth and action gameplay that ultimately rewards carnage more than tactics. While immersive sims like Deus Ex: Human Revolution or Dishonored actually feel like sandboxes, Far Cry 3 feels like a wide corridor - there's a lot of breathing room, but you're ultimately being funneled down the same route as every other player.

There's nothing wrong with guided experiences, of course - The Last of Us Part II proves that you can tell a profound story, offer mechanical nuance, and encourage multiple styles of play while very clearly forcing you down a certain route. But it wears that on its sleeve, and lets players use their preset corridors however they want - making everybody's playthrough unique while they still hit the same story beats.

Far Cry 3 doesn't offer the same freedom. The game constantly reminds you that you can do whatever you want, but really, you can't. You see that mountain? You can't climb that mountain until your number is high enough, you take out three enemy bases, and you unlock an arbitrary pip on your skill tree. Ubisoft fools you into thinking you have options, but the leash is always in their hands.

Trickle Down Game Design

The consequence of Far Cry 3 being a hit was that Ubisoft saw a golden opportunity to do it again. After we got our last few gasps of ambition, their marquee titles began to run together. Soon, Assassin's Creed and Ghost Recon got their big reboots, Watch Dogs applied the Far Cry structure to a sprawling metropolis, and Ubisoft put out a racing game that somehow felt like yet another guided big map excursion.

And, of course, they found a way to make more money off of it. If you want to breeze through the early parts of a game, just pay for the $100 edition at launch. If you're stuck, funnel money into your weapons so you can breeze through the game. If you don't want to grind crafting resources, just pony up a few extra bucks for a bundle of ingredients. With each subsequent year, Ubisoft carefully analyzed every single element of this style of game and found all the right places to weigh down with microtransactions.

Time for another pop quiz. What 2010's Ubisoft game is structured around collecting things, upgrading them with resources scattered around the map, and encouraging players to spend money to bypass the whole system altogether?

If you answered Assassin's Creed Origins, Assassin's Creed Odyssey, Ghost Recon Wildlands, Ghost Recon Breakpoint, Far Cry 4, Far Cry 5, Far Cry: New Dawn, The Crew, The Crew 2, The Division, or The Division 2, congrats - you aced it! Wait, are there other ones? Yeah, probably.

Point is, Far Cry 3 popularized this structure for AAA games. It weened players onto the idea of wasting time on an ultimately limited experience, then proceeded to stretch that amount of time out with each subsequent year. The longer games got, the more players would get tired of fighting an uphill battle. The more tired players got, the more chances Ubisoft found to offer helpful little time savers. The more of these they offered, the more expensive they got with each passing year.

That's how you arrive at catastrophically bad games like Far Cry: New Dawn or Ghost Recon Breakpoint. These games are tremendous wastes of time in terms of recycled content and padded length, and offensive with their constant encouragement to throw money down on microtransactions. On almost every mechanical and structural level, these games represent Peak Ubisoft: disposable, pointless, and predatory.

But there's another component here - one that really drives home Far Cry's culpability.\

"What About Both Sides?"

See, "boring time filler mechanics tailor-made for microtransactions" are just one half of the true Far Cry experience. The other half is a refreshing, delightful brew of tired moral ambiguity, toothless attempts at shocking the player, and a heaping helping of racism.

Once again, Far Cry 3 set the stage here. The game's quirky antagonist leads an oppressive regime, and players are forced to ally themselves with a faction to topple them. As they progress through the story, they realize that their side might also have done some bad things. As those bad things happen, the player is then invited to think, "huh, both sides here are wrong!" By game's end, allying yourself with your initial faction proves to be a dicey choice, and you're left thinking, "wow, who was the real bad guy all along?"

Does this sound familiar? It should, because it's the exact narrative arc of Origins and Odyssey, of Watch Dogs, of Wildlands, of every Far Cry game since 2012. Scrappy rebels are often just as bad as ruthless dictators, and ruthless dictators might not be so bad once you get to know them. Ubisoft games are consistent in one thing - a devotion to making the world look like an evil place worth destroying. No side is worth taking, and every person is evil in some way.

The problem is that this isn't how real life actually works. There is legitimate good in this world, and there is legitimate evil. For Far Cry 4 to have the gall to stumble into a struggle for liberation and paint their oppressors as ultimately sympathetic is absurd. For Wildlands to show a war-torn Bolivia, but ultimately vilify rebel fighters and lionize the US government is caustic. For Origins to depict the conquering of Egypt as a gradual, almost cordial affair with good people on both sides is to misunderstand history.

But perhaps the worst offender of the bunch is New Dawn, a game that's more willing to rehabilitate a rapist cult leader's image than it is to empathize with two young black women robbed of their future. The game bends over backwards to redeem Far Cry 5's Joseph Seed because he's estranged from his son, but completely damns Mickey and Lou for daring to try and survive in a post-apocalyptic wasteland. Seed is painted as a sympathetic figure, while Mickey and Lou are irredeemably "angry" and "violent." The game concludes that a new, radical way of living (characterized by rap and neon colors) is ultimately wrong because they drive out remnants of pre-nuke America, but a recreation of the American homestead (characterized by '50s golden oldies and white people) is worth committing genocide for. Despite, y'know, that very society being propaganda for one of the most violent imperialist regimes in the world.

This is the morality of Far Cry - and of most Ubisoft games made in the past decade. Fighting oppression ultimately makes you as bad as the oppressor, and the oppressor might be better than you gave them credit for. Games like Wolfenstein: The New Order and Mafia III do a great job of reminding you that that some evil is just that: evil.

Ubisoft, apparently, didn't get the memo.

Reduce, Rinse, Repeat

There are other elements to Ubisoft games - namely a pattern of colonialist sympathy and fascist whitewashing - that are worth calling out. But I think better writers have touched on that - especially Dia Lacina's biting and brilliant review of New Dawn, Joshua Rivera's takedown of Wildlands' jingoism, and Austin Walker's deep dive into Far Cry 5's politics, for starters - and I think this article's too damn long already.

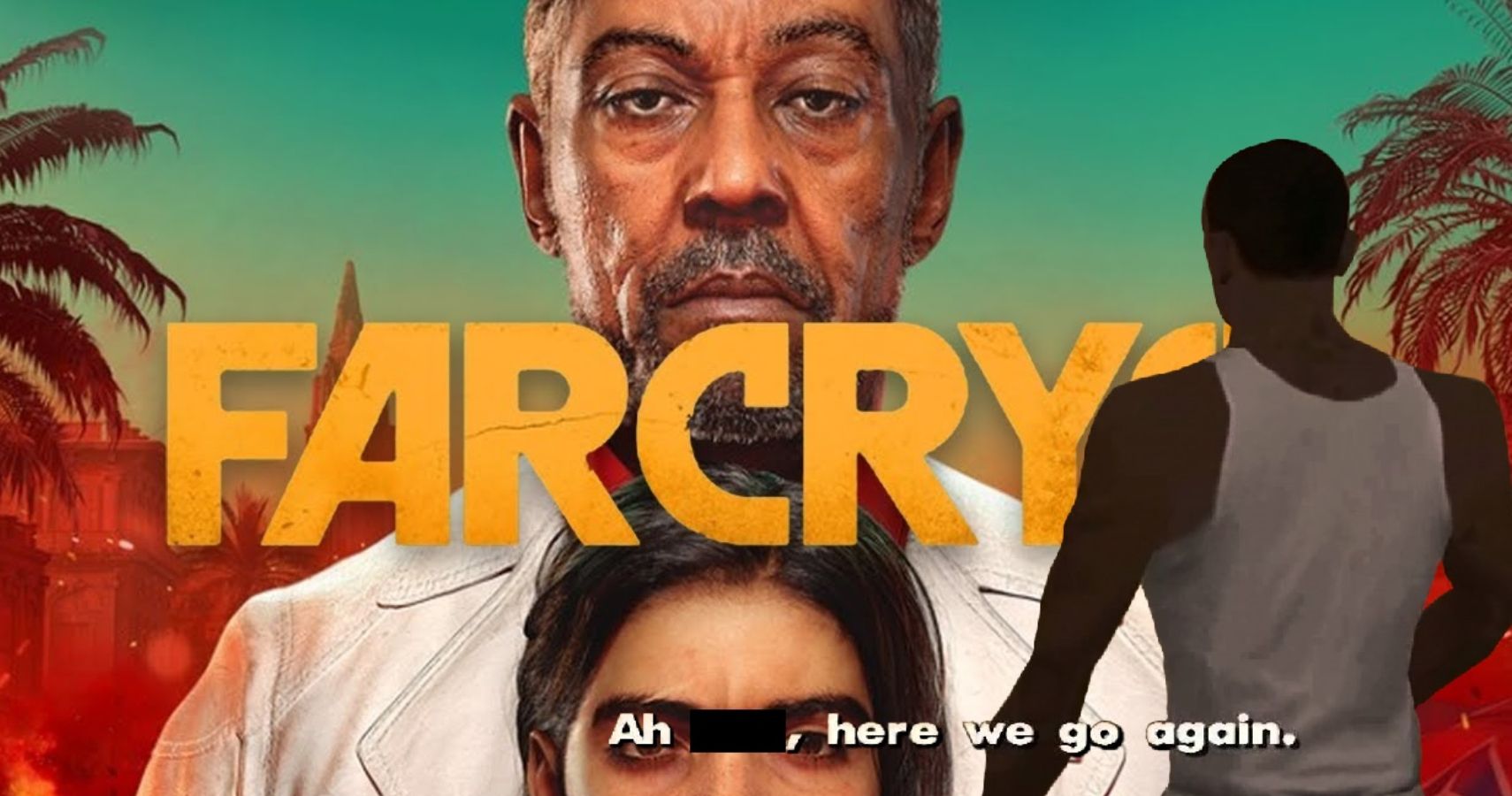

Now that we're staring down Far Cry 6's barrel, and now that great critics are already calling out its potentially heinous portrayals of its Latinx characters, it's a good time to ask - do we need another decade of Far Cry? Do we need another decade of Ubisoft recycling its same structures, rehashing its same pay-to-win schemes, and peddling its same centrist drivel under the guise of being thought-provoking entertainment? Do we need to play the same goddamn game for years on end, whether it takes place in "post-Brexit" England or "rollicking Viking times" England?

Ultimately, that's up to you. But from where I stand, Far Cry 6 looks like the latest in a long line of games that have been fundamentally identical in their politics, their mechanics, and their anti-player practices. From where I stand, I really don't have an interest in financially enabling an abusive company to keep reheating the same expired Kid Cuisine for another ten years. And from where I stand, there are more interesting things happening in other corners of this industry that are worth supporting and propping up.

Maybe that's not the case for you. Maybe this time, you think, will be the time that Ubisoft does something different. Maybe, you figure, if you keep buying their games, they'll have a financial incentive to take more risks and to stop kowtowing to the status quo.

Maybe if you do the same thing, over and over again, and expect a different result, it'll work out for you.

Hm. That reminds me of a famous line from a video game. Can't remember which one, though.