Mobile gaming is a tough business. It’s an incredibly saturated market with new games pouring out each and every day, their free-to-play nature means a reliance on microtransactions that are not only controversial but require constant player interaction, and the medium as a whole often keeps mobile gaming in a separate box. We spoke to developers from IT Territory, Pixonic, and Whalekit (all studios under the My.Games umbrella) about what challenges and changes have occurred in the mobile industry recently.

According to Maxim Fomichev, lead producer of Pixonic’s War Robots, the biggest issue is the market’s unpredictability. “Whenever you launch the game, you're trying to guess what the audience will like, and what it will reject,” he says. “So it's always about the number of tries you make. So there is no silver bullet or recipe to success. So you just have to try different things and try to find what audiences like. It doesn't matter what kind of game it is, there will be some people who will like it. So the developers’ job is to find that combination of art style, game design, time to kill when it comes to shooters, or any other combination that will have the widest audience possible. When we launch the game with the know if this product will be a hit, would be a mediocre game, or would be a failure. There's really no recipe for that”.

Vladimir Markin, the COO of Whalekit, also described unpredictability as the biggest challenge in the mobile space, but said the ways developers can view metrics has helped overcome that somewhat, or at least understand where games are succeeding or failing. “It's mostly luck,” he admits. “The only thing that can minimize it is our researchers or analytics on similar projects. If we see that the retention and the monetization metrics are on par, or higher. with what we saw in similar projects, that's a really good sign.”

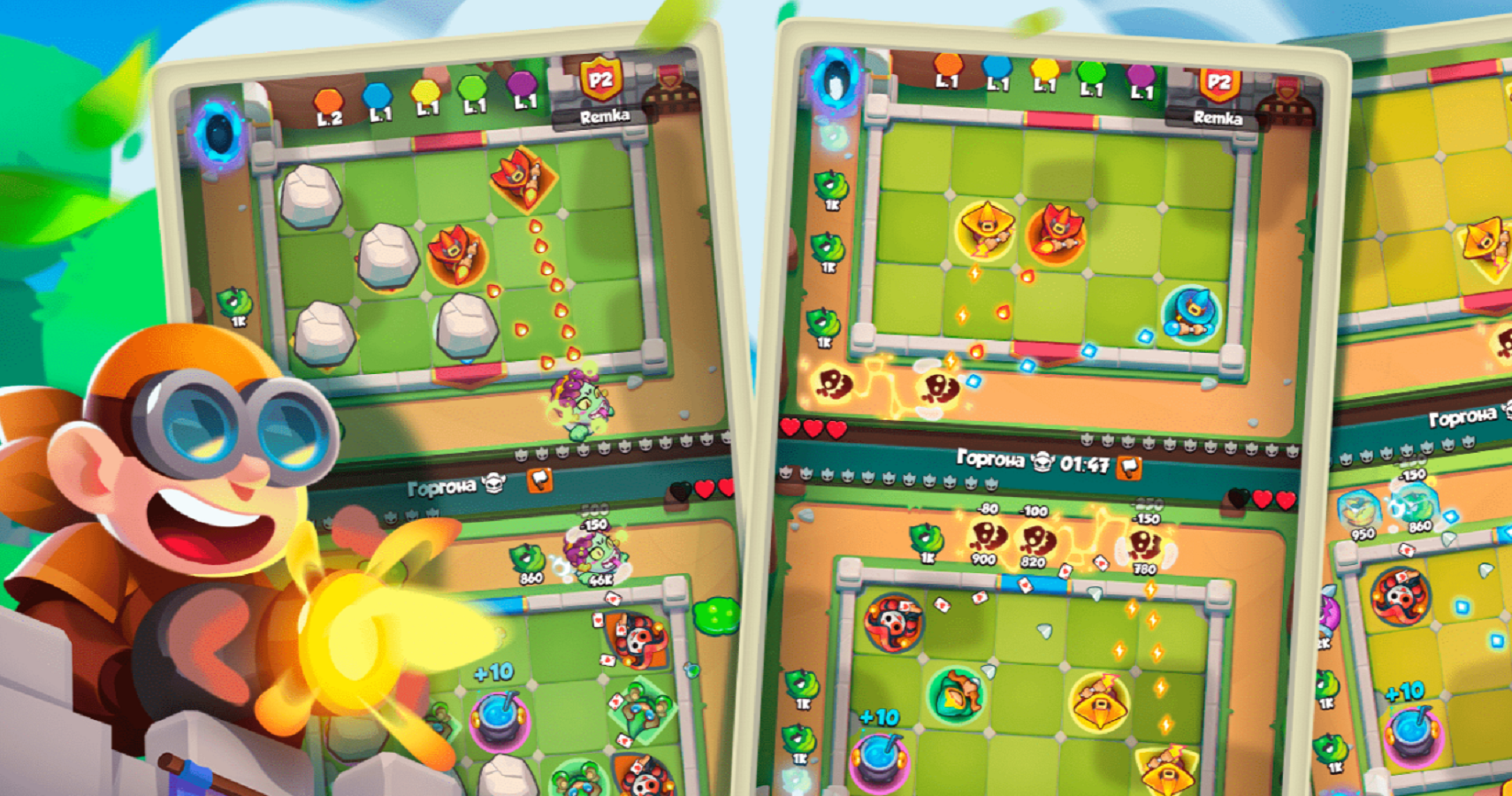

Kirill Lichmanov of IT Territory also echoed these sentiments, adding that the strategy has moved from saturating the market to refining games that will stand out - fewer releases of higher quality over throwing everything at the wall to see what sticks. “When you make a free-to-play game, there are so many [potential players] in the market, he says. “So the studio's biggest task is finding a niche - that's crucial for free-to-play right now. You must make a game that will have a long life. That's the biggest difference with the market. Five years ago everyone made little games, or tried to try to just make the most money from the players. So they can make the next product and the next product, but now you can make, like, two games a year. We are trying to make big, long lasting products that will gather audiences in the long term.”

One of the ways Whalekit tries to ensure its games will hit as wide an audience as possible is by holding internal Shark Tank meetings, where anybody in the studio, no matter what their role is, can pitch a game. “We allow everyone from the studio to present their own ideas,” Markin explains. “It's not only producers or management, it can be everyone, including the junior QA person. For the sharks, we use a combination of managers, producers, and a few persons from each discipline, like engineers and artists, and that allows every idea to have a equal treatment - not one person decides, but around 15 experts.” These experts then score each idea out of five, based on a number of factors including how long the game would take to make, how relevant it is in the current market, how different it is to Whalekit’s roster, and its likelihood of long term success. The games that score highest then move into the pre-production stage.

Of course, the biggest task in the free-to-play space is making enough money to survive. Typically, players associate these games as being kept alive by ‘whales’ - the big spenders. To hear Fomichev tell it though, it’s not that simple. “The reality is that the vast majority of the income comes from the whales,” he admits “But that puts the developer in the situation where you depend on a few players, right? For the five million monthly active players of War Robots we have about 10,000 of those being whales. So if they leave, we're done. Well, not done. But we are in serious trouble, right? At the same time, the dolphins - the guys who pay hundreds [of dollars] - they are the wider audience. The ideal situation is when you have both categories monetized and both [whales and dolphins] happy. Then there are the free players, so you have to find a balance between the different paying users, and the non-paying users. And this is sometimes really hard.”