Over the last decade, indie studio Supergiant Games has garnered widespread acclaim for its thoughtful approach to making games. Its first three releases -- Bastion, Transistor, and Pyre -- all felt disparate from each other thematically, yet connected by the unique sensitivity that Supergiant brings to every one of its titles. Then, in 2020, the studio released Hades, a stunning roguelike based in Greek mythology that became its most successful game yet.

"Hades is the first game that we've worked on where we deliberately set out to build on elements of our previous games," Supergiant creative director Greg Kasavin explains. "For our previous games, we were focused on making sure that they each had their own distinct identity. But with Hades, we thought we should be able to build upon some of the best ideas we've had in the past, rather than discarding everything we've learned. Hades would not exist if not for Pyre."

Though Hades' gameplay more closely resembles that of Bastion, the themes that drive its narrative are highly reminiscent of those explored in Pyre, a role-playing game about a group of characters fighting their way out of exile. There isn't any actual fighting, though -- the combat, which occurs in events called "Rites", is best described as "fantasy basketball".

Pyre didn't find the same widespread success as Hades, with some players finding its unconventional gameplay and dense, text-heavy storytelling off-putting. Still, the ideas it introduces will be very familiar to Hades fans, to the point where it sometimes feels like an unintentional prequel. Both games are about navigating the relationships you form with these large casts of characters, all with different motivations but held together by a common purpose.

Or, as Kasavin puts it, more simply, "they're both about trying to get out of hell."

What truly sets Hades and Pyre apart is the way they approach failure. There are no checkpoints or 'game over' states. There's no punishment for failing at all, actually. When you die in Hades or you lose a Rite in Pyre, the story continues. Just as in the real world, you live and you learn.

"It's something intrinsic to most games with any sense of challenge, right?" Kasavin asks. "You fail and go back to the checkpoint, or lose a life, or something. But we like to call those underlying assumptions into question. Why do those conventions exist at all? So with Pyre, we said there would be no 'game over' at all, because thematically this is a game about learning from your losses, picking yourself up after the defeat, and seeing something through, no matter what happens."

It's a philosophy that forces you to relearn your fundamental understanding of how games work. Historically, games have been built around the avoidance of failure. We develop habits of reloading our save files when we think we might fail, to avoid the disappointment of hitting the point where we actually do. Hades and Pyre diverge from this by challenging the idea of what it means to fail.

"It's hard to unlearn that and accept that losing is not only okay sometimes, but can even be enlightening and interesting," Kasavin says. "In Hades, you have no choice but to die, and move forward. In a roguelike game, the beauty of it is how it's different every time you play. And the part where the story advances, after you die -- we wanted to make that moment almost something to look forward to."

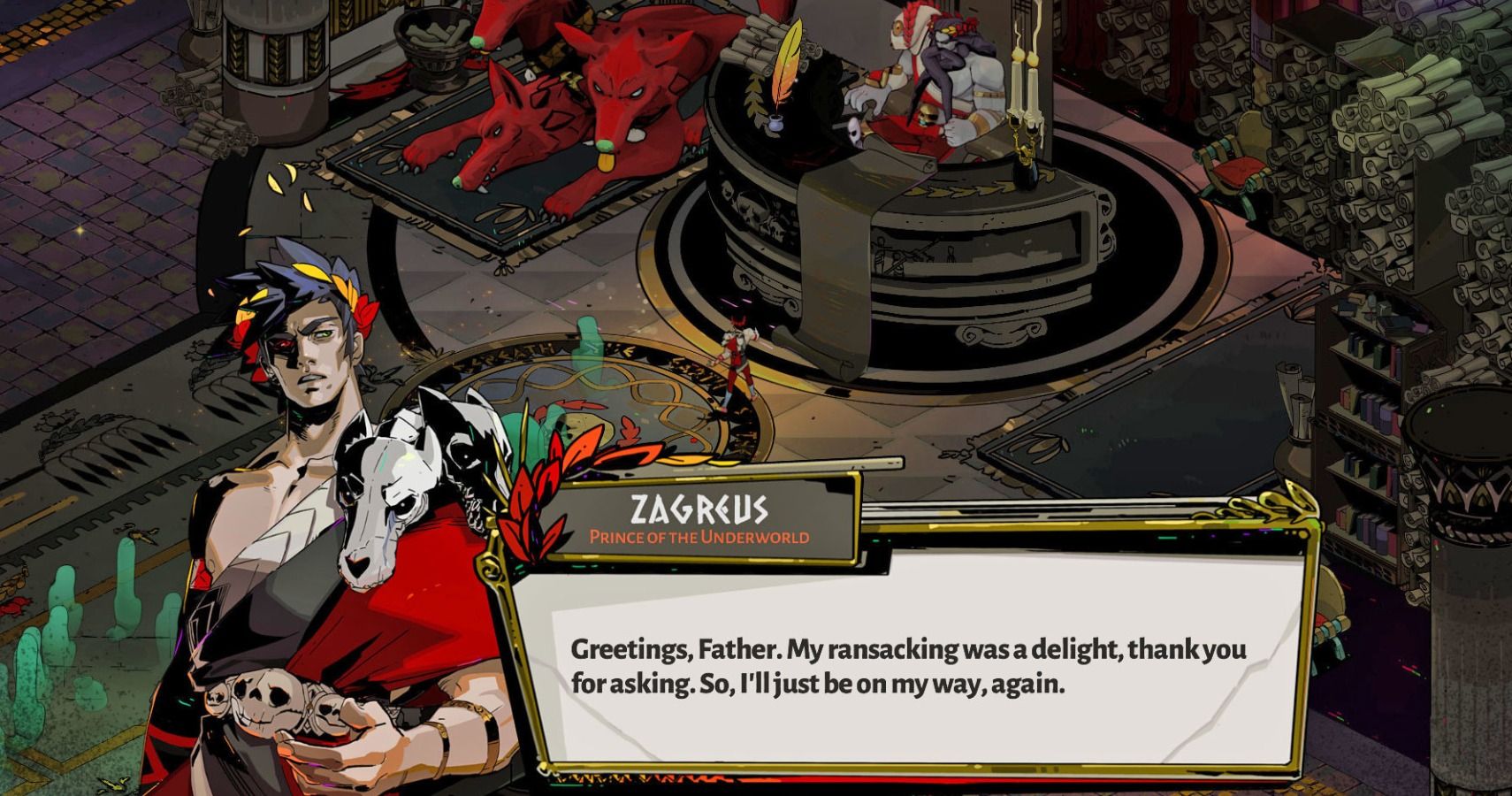

Hades soothes the sting of failure by making death a necessity. After each death, you're sent back to the House of Hades, a central location where you can talk to characters and advance side plots that enrich your understanding of the world. The focus on relationships shaping the way you play is something Supergiant experimented with in Pyre, but Hades' format allowed the studio to take it further.

"We were drawn to the human qualities of these Greek gods," Kasavin explains. "For example, we were interested in presenting Hades as the complicated character that he is, and hopefully, over the course of the game, you start to understand him. We like to make games where you understand why certain characters made the choices they made, regardless of whether those choices were good or not. I think games have a powerful ability to do that, because you spend a lot of time in their world and you get to explore relationships in a different way than you could in other media."

In both Hades and Pyre, the ideas of family and togetherness are huge driving forces. While Pyre is more of a found family narrative, the family you deal with in Hades is your biological, mythological birthright. These dynamics almost seem in conversation with each other as both games delve into the nature of attachment, those you form and those you overcome.

"Pyre's characters aren't related by blood -- in fact, the relationships where they are related by blood are some of the worst in the game," Kasavin says. "But they bond with each other to the point where, even if they're separated, they still feel as though they're together. With Hades, we're contrasting that with the idea that you can't help who your family is, you're just born into it. And in Hades, they could kill each other over and over, but it doesn't solve anything. They eventually have to work through their problems in some other fashion. We make a case for the possibility that they can move past some of their differences."

Hades and Pyre are both incredibly dense games. No two people's experience of either game is likely to be the same, with millions of possible permutations packed into both. As such, it's impossible to see all of Pyre's content in one run. But one of the game's best moments occurs when, in a pivotal Rite, an allied character Pamitha is pitted against her bitterly estranged sister, Tamitha. Despite the bad blood between the two, Pamitha privately begs you to let Tamitha win. The game presents you with the option to lose on purpose. It's a difficult choice and a moment where Supergiant's unorthodox approach to the very nature of failure really shines through. The taboo of failing is completely discarded. All of a sudden, it becomes just as viable an outcome as success.

"Not everyone even has that particular interaction, but that's one of my personal favorite moments," Kasavin admits. "Because it's where you're very directly confronted with this idea that maybe it's more important for your opponents to win here than you. We were very interested in that, thematically -- this idea of the zero-sum victory, where my victory is your loss. Not everybody wins, which is a bit of a bitter idea. But it's very true to life as well."