As an avid podcast listener, I’ve heard a lot of advertisements for Hunt A Killer in the last year, and I’ve always been intrigued by its core concept. Hunt A Killer’s main product is a subscription box that lets you unfold a single mystery over several sessions, but I had been hesitant to commit my time or money to a six-month subscription to a game I wasn’t sure I’d enjoy. These two standalone games, however, are much easier to get into, with session lengths of two hours or less.

In these games, you (and a group of friends, if you like) are a private investigator, going through evidence sent to you by a contact in order to solve a case. One of the games, Homicide At The Heist, was an Ocean’s Eleven-type scenario. A heist to steal a diamond went wrong, the safe-cracker died, and his brother hires you to find out what happened. The other, RIP At The Rodeo, was far more interesting - a rodeo clown is gored by a bull, and his ex-wife suspects foul play. She asks you to help find out who caused his death.

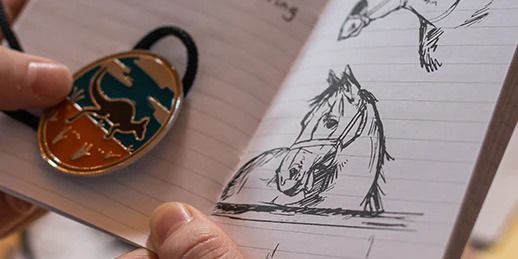

A selling point of these games is that they use a mix of physical and digital media, though they lean on the digital to different extents in each game. Some of my friends liked it, and some didn’t - I felt that the game’s strength lay in its lovingly-designed props, though I did quite enjoy looking at screenshots of messages between the game’s characters. There’s plenty of information in the digital media, but playing felt best when I was hands-on with the high quality props. I particularly liked that there were locked boxes in both sets, gating information until you figured out how to unlock it. It’s important to note here that having a digital component helps with accessibility as some of the evidence is handwritten and it’s transcribed in the digital resources, but I don’t necessarily think it always added to the gameplay.

It never felt like I was having information withheld arbitrarily, which is a big achievement for a game that has to balance gameplay with story. Across the two games, we read pages of transcripts, autopsy reports, police interviews, and event brochures, some of which helped us break into password-locked folders and figure out combinations for physical padlocks. As we built timelines, checked alibis, and discussed possible motives, we could feel the story getting sharper, as if a fog had cleared. There were red herrings, but they felt like complications left over from humans being messy, not obstacles added to make the experience harder.

It helped that the writing was very funny. A few times, I laughed out loud reading a piece of evidence out to my friends, and in RIP At The Rodeo especially, the characters grew on me. They all had their own personalities and drama, and it came through in every piece of writing within the game. For example, you find the victim’s journal and it’s peppered with minor misspellings and written in sharp character voice, showing you more about him instead of telling you. Or you’ll read a transcript of a conversation, and a character will say something stupid and get made fun of by the rest of the group. Though the quality of the puzzles differed from game to game (I preferred Rodeo), the quality of the writing stayed high. A nice touch is that after you figure out who the killer was, you get a letter that tells you what happened to the rest of the characters, resolving all the extra plot lines.

I’m not sure if the difficulty across the two sets was inconsistent, or if we were just tired after solving the first and didn’t have as much energy for the second. RIP At The Rodeo was fairly easy if you had the patience to read through the evidence closely, and we didn’t need to access the game’s hint system. Homicide At The Heist, however, had us banging our heads against the wall while trying to open a locked box, because of our refusal to look at the hints. Eventually, I started spinning the wheels of the padlock to crack it, which worked, and after seeing the solution we knew we would never have guessed what the combination was. Overall, Heist felt a lot more circumstantial and abstract than Rodeo, which was more personalised and concrete.

These games made me feel like a genius when I found a hidden clue, then an idiot when I stumbled over a puzzle, and then a genius again when I solved the mystery. They made me feel like an armchair detective, solving crimes from the comfort of an old couch in my friend’s flat. They made me feel like a conspiracy theorist, coming up with outlandish theories as to what happened and trying to find evidence to confirm it. It was a lot of fun to play a well-written mystery game with friends that I didn’t have to prepare for, because everything was already in the box, and you get some cute souvenirs in each box, to boot. I just wish they’d lean into their strengths in good writing and well-made props instead of shoehorning in digital media where it’s not needed.