It's hard to believe Ico will be 20-years-old later this year. Fumito Ueda's 2001 masterpiece was my introduction to thinking a little more critically about the intersection of play and how we process and engage with stories. Ico presents a stripped-down tale of childhood love and loss but asks that we engage with it a little differently than other games of its era. I regard Ueda's painfully emotional trilogy as some of my favorite games, and even if Ico isn't at the top of the three, it introduced me to themes and design choices that shaped my understanding of what games could be.

While games before and after Ueda's Ico accomplished a more abstract storytelling approach, one without spoon-feeding you the intended player reaction, Ico is arguably a classic. It's a lesson in world-building, a test for understanding level design, an imaginative story that can only be experienced through play. If I try to explain to you what happens and how it made me feel, it doesn't quite make sense. Ico feels like something that can't be repeated through just words or passively watched.

I say that as a fan who just got done reading an expanded, novelized form of Ico in the book Ico: Castle in the Mist. It's a beautiful rendition in its own way, and probably one that can be enjoyed by those of you who haven't played the game, but it's still no substitute for playing as Ico yourself.

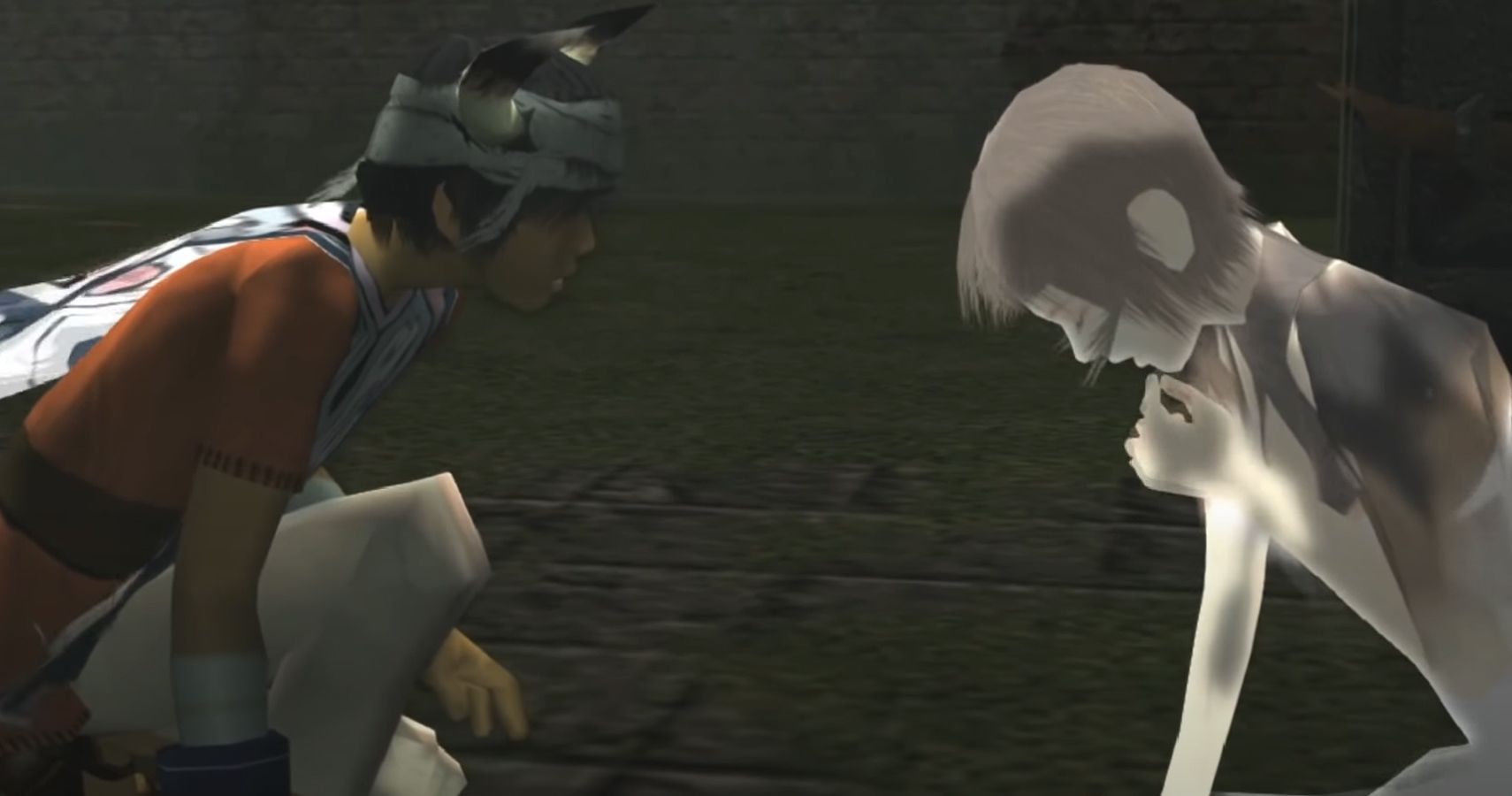

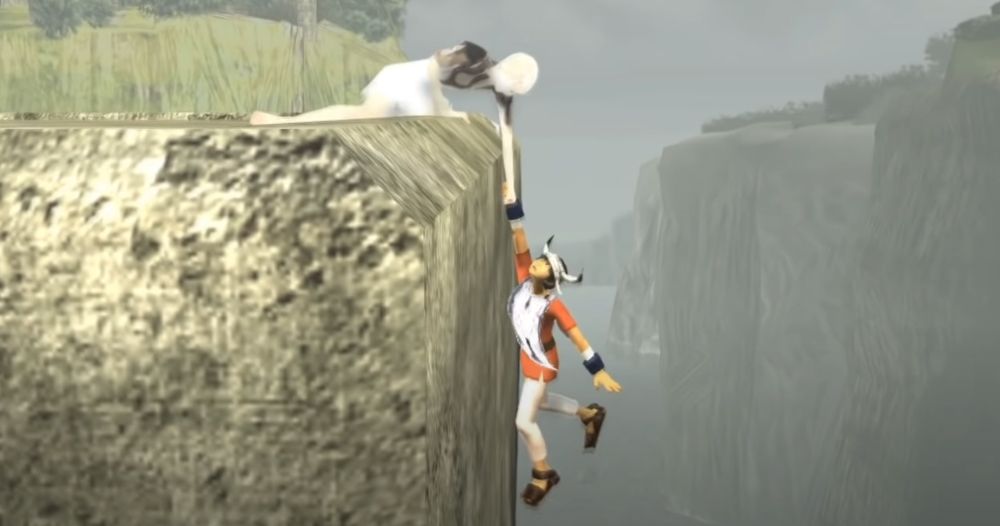

Meeting both Ico and the game's ethereal young girl, Yorda, introduces a connection through play we've seen emulated several times for nearly two decades. As Ico, you'll grab Yorda's hand and move at a panicked pace through the game's ancient castle backdrop; often dragging Yorda along, Ico moves inelegantly. His awkward motion clashes with somber melodies and the game's meticulously organized art style. But that’s the point - Ico is supposed to be frantic. Ico himself has always remained a favorite character of mine for the childlike sense of wonder and terror he has towards his surroundings, never betraying what it is to be a child in his situation.

The first thing little Ico does is pick up a stick to protect himself and Yorda. The game asks this tiny child to rescue them both, but his panic, bravery, and movements make him believable. Ultimately, Ico overcomes the castle's queen and sinister, shadowy creatures because this is a hero's tale. But even in these impossible, larger than life scenarios the game tasks him with overcoming, he never feels bigger or more powerful than his foes. And how it feels to be Ico is just as crucial in understanding his story.

Ico's sound and music play much like its art direction, opting for minimalism over extravagance to make bigger moments more punctual. Even Yorda herself does little to advance the dialogue between her and Ico, as she speaks an entirely different runic language you can't comprehend as the player. The game's few moments of dialogue are only met in circumstances like Ico facing off against the game's evil queen, but even then, those scenes are few and far between.

Ico's minimalist approach is something we saw perfected in Shadow of the Colossus and then again in The Last Guardian, but it all began back in 2001. Ueda's trilogy is a masterclass in storytelling, one that requires engagement — something you have to do, not watch. And while we are celebrating two decades now of Ico's brilliance, the game is timeless, a title that could see a re-release every generation with no need to justify its age.