For decades, veteran game developer Josh Sawyer has been designing big, deep, dense RPGs. Games like classic D&D dungeon crawler Icewind Dale, sublime Infinity Engine throwback Pillars of Eternity (the sequel to which is one of the best RPGs ever made), and beloved Fallout sequel New Vegas. But Sawyer's next project is something very different indeed. Pentiment (more on that curious name later) is a narrative adventure game set in 16th Century Bavaria.

While it will feature role-playing elements and a branching narrative—things Obsidian is known and loved for—they'll be presented and packaged in a way that we've never seen from the studio before. From the moment I saw the reveal trailer at the Xbox & Bethesda Games showcase, I had to know more about it—so I asked Sawyer to talk me through the origins of the idea, and what we can expect from Pentiment when it launches on Xbox and PC in November.

"I had a girlfriend who was super excited about Night in the Woods," he says. "I played it and I was a little surprised, not in a bad way, of how you just kinda vibe in it. You walk around and chat to people and do little minigames and go through a story. I thought it was cool and I loved the art style." Sawyer went on to play Oxenfree and other games with a focus on narrative, distinctive art direction, interesting characters, and minigames to break up the story. "I liked the concept," he says. "But I wasn't like: I gotta make one of these!"

That didn't last long. "Later, I had the idea to make a historical game in a similar style. One that was laid back and approachable. It wasn't until about two and a half years ago that I really thought we could make a game like this, and that was pretty much the genesis of what would become Pentiment." In the game you play as Andreas Maler, an artist working on illuminated manuscripts in Kiersau Abbey, a monastic scriptorium. His work is interrupted when someone is murdered and his friend is accused of the killing. Maler takes it upon himself to solve the crime—a decision that triggers a story spanning multiple generations.

A historical murder mystery is certainly an intriguing and unique premise for a video game. But how much of a detective game will Pentiment be? I saw someone on Twitter describe it as 'medieval L.A. Noire' and I'm wondering how accurate that is, if at all. "I wouldn't say it's a detective game," says Sawyer. "There is a murder mystery at the heart of it, but I keep saying it's a narrative adventure to draw a distinction between the two. We don't have hardcore detective mechanics. There are no logic puzzles involving excluding people or confirming alibis. We actually did do that in a prototype, but it wasn't what we wanted."

As Maler you are investigating a murder, but the familiar structure of a police procedural doesn't really apply to the 16th Century. "There's not like a high burden of proof in this era," says Sawyer. "It's more about you going around learning about the motives people have, and about them as characters. From the suspects, you then need to figure out who you think you should pin it on. You're not an official detective. You're close to someone accused of murder, and you're the only person who has a really strong interest in proving that he didn't do it."

The abbey's archdeacon is the person who's really in charge of the investigation, and you can turn over evidence for him to look into. But whoever you point the finger at will almost certainly be killed as punishment, which places a heavy burden on you. "We want the player to ask themselves what they value," says Sawyer. "If you think the most important thing is that the person you believe is responsible for the crime suffers for it, that will lead you towards certain characters. But if there are characters you just think suck, and you think deserve to be executed, maybe they're the people you pin it on."

But whoever you choose to punish, their absence will be felt and people will take notice. "This is a story that takes place over many, many years," says Sawyer. "People will remember that you're the person who pinned the crime on a certain person. That's the heart of the choice and consequence of our story." Interestingly, Pentiment won't tell you if the accusations you make are right or wrong. This is a concept more traditional detective games like Paradise Killer and Sherlock Holmes: Crimes & Punishments have used to great effect.

"There are a bunch of people who have motives, and they're more or less plausible based on the evidence you find and your own personal opinion," says Sawyer. "You just have to deal with not knowing for sure, and some people will question your decisions. There's always gonna be someone who will always believe a person accused of a crime is innocent, so I hope that creates some uncertainty. On our side there's no canonical true killer, so we won't be telling the player they got it wrong. That's not really the point. It's more like: here's what you found out, this is the choice you made, and here are the consequences."

As for Andreas Maler himself, I wonder how playing as, of all things, an artist will colour Pentiment's story and gameplay. "You're finishing up your journeyman years and you're about to become a master. You're pinch hitting, basically. They don't have enough monks to finish the manuscripts that have been commissioned, so that puts you into the heart of this monastic scriptorium and the community surrounding it. You don't live in the abbey: you live in the town, which makes you able to move back and forth between them fairly fluidly."

Art, writing, and script are all central to the story in Pentiment, which makes playing as an artist especially relevant—and useful. "His skills come up in how he deals with clues, letters, and notes that he finds," says Sawyer. "Thematically there's a lot of stuff about the artist's role in documenting the world and recording history as it is—or as they believe it to be. But the main thing is that he can move between these two worlds, between the secular and the ecclesiastical."

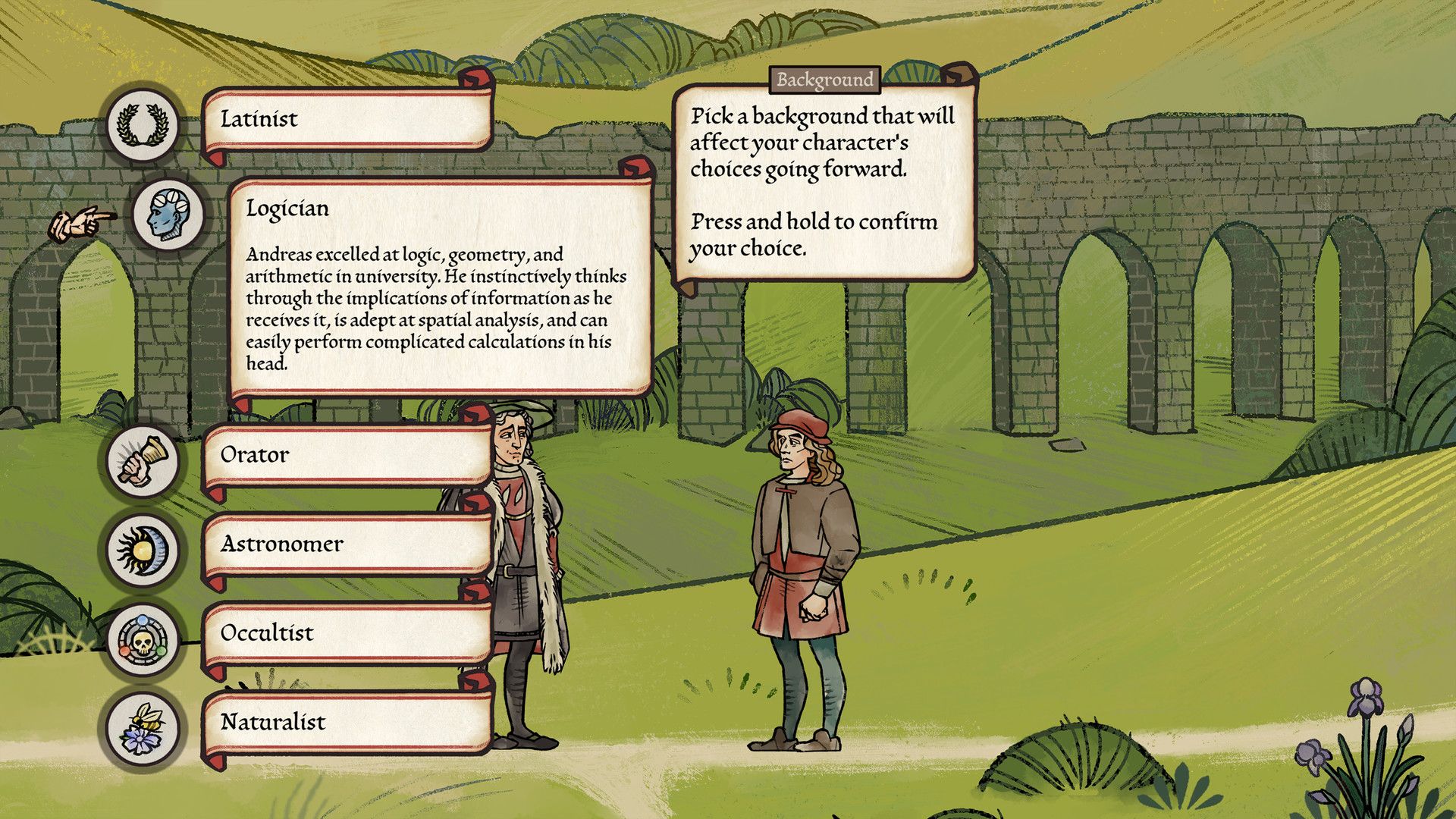

In some ways, Maler is a set character. He was born in Nuremberg and comes from a family of artists. He attended the University of Erfurt, which people from his social class didn't usually get to do. He dropped out to pursue the life of an artist, going on his wanderjahre—a period spent travelling abroad before becoming a master. But tapping into Obsidian's role-playing expertise, you can choose where he travelled to, what he studied at university, and what kind of personality he has—all of which will impact the story and dialogue choices.

"If you look at people like Albrecht Dürer, an artist from this period, they travelled extensively in Europe and learned from the masters," says Sawyer. "You can choose where you spent these years. Did you spend your time in Flanders or Basel? These were very big art centres at the time. What did you actually study in university? You can pick from the traditional liberal arts. Logic, grammar, astronomy, and a number of others, such as the occult. You can also choose his lifestyle. Is he a hedonist who just lives for pleasure? Is he a craftsman who is very dedicated to his art? A businessman who wants to make a career?"

You're defining a role-playing character, and the dialogue options you have will reflect your experience. "If you lived in Italy, you know Italian," says Sawyer. "But unlike a lot of our other games—people have criticised us for this and we're trying to address it—just because a dialogue option appears doesn't mean it's a good idea to pick it. Very often you'll come across as a know-it-all or a show-off. Basically being socially awkward. Just because there's an opportunity to talk about your knowledge, interests, or past doesn't mean it's a good idea."

Sometimes saying the wrong thing can negatively impact a conversation. "This gives you a broader palette to work with," says Sawyer. "We want players to really think about the options they pick rather than just blindly selecting them." This addresses a common problem in RPGs, especially in the Infinity Engine mould, where you'll feel compelled to exhaust every conversation option—even if it means saying or doing something you wouldn't otherwise. I love the idea of a dialogue-driven game where you have to choose your words carefully, rather than just speaking until all the choices are satisfyingly greyed out.

What about the game's unusual title? A pentiment is an image hidden in a painting. A layer of paint is removed (sometimes naturally through ageing, sometimes intentionally) and people switch positions, details change, or eyes look in different directions. "There's a lot of significance to it," says Sawyer. "There are a bunch of obvious things, like manuscripts and paintings hiding things under the layers. You're uncovering a mystery, and art is very important to the story. But there are other meanings to the word that I think will become more apparent as you play through Pentiment and reveal more of the story."

I ask Sawyer about his very specific choice of time period. What makes 16th Century Germany an interesting backdrop for an adventure game? "At this time, the Holy Roman Empire was dealing with two very big events," he says. "The reformation started, Martin Luther started to become well known, and his theses were reproduced and spread throughout the empire. Then there was the German Peasants' War, which spread out into the adjacent territories of the Holy Roman Empire—including Bavaria, where the game is set."

Kiersau Abbey and Tassing, the nearby village, are located in a fairly remote area—but they're also on a trade route. "There were these big trade routes that would go over the Alps, the Imperial Way, and this means the abbey is adjacent to these major conflicts," says Sawyer. "So there's a lot of traffic that comes through, a lot of visitors, which means you can meet people who aren't just Germans. There's an Ethiopian character, for example. Ethiopians were at the Council of Constance a hundred years before the game takes place and they were able to travel within this realm. There's just a lot going on in this time period."

When it came to researching it, Sawyer was already well equipped. "I have a degree in history that was more or less focused on this time period and this place, so I went back and looked at my old books," he says. "I had to dig through my brain for old references too. But we also have three historians as consultants: Christopher de Hamel, Edmund Kern, and Winston Black. They're giving us a lot of insight, because sometimes I hit dead ends. I don't have a PhD, I have a bachelor's degree, so I'll write to them and ask them if something is plausible."

Sawyer wanted to know more about how people hunted in 16th Century Bavaria: how they dressed, how they did it, the weapons they used. He asked Edmund Kern for advice and was sent a 19th Century German text. "It was printed in fraktur, or blackletter," he says. "I took a day and read through it and translated it, so there's definitely been a lot of work put into getting the details right."

You'll also be creating your own history in Pentiment. Sawyer's previous games have been set on a linear, contained timeline, but this story spans several decades. I ask Sawyer about the challenges of writing such a far-reaching narrative. "It opens up a lot of opportunities, but we have to think very carefully about how we plot things," he says. "Each act of the game is a relatively tight period of time. You make choices and time moves forward in a very strict way. Those are very focused, but then we can jump forward many years before the next act. It's not like most RPGs where it's this one, long continuous period of time."

It's challenging, Sawyer says, but he doesn't consider it a drawback. "There are choices where you'll see generational changes, or significant changes in a community. Because of this tight relationship between the abbey and the town, you have a chance to see in great detail the ramifications of your choices." Choice and consequence is something Obsidian does better than most developers, and I'm excited to experience the studio's knack for impactful branching storylines placed in the context of a more straightforward narrative game.

Pentiment is also an attempt by Obsidian to bring its stories to a wider audience. As great as games like Pillars of Eternity are, they're not exactly the most approachable. "We didn't want hunting around for stuff being the focus of the game," says Sawyer. "Movement is as simple as we can make it. It's very accessible too. There might be people who are not super into hardcore games—games that are very demanding in terms of controls and systems—who might like the look of Pentiment. They might be drawn in by the art or the setting. It's more about exploration, atmosphere, and exploring at your own pace."

For Sawyer, whose Tumblr reveals a deep passion for the intricacies of role-playing combat systems, working on a game like this is refreshing—and also a chance to improve as a writer. "Because the systems are so light in Pentiment, it's nice to be able to focus almost entirely on story and presentation," he says. "I'm playing more of a creative director role on this project than a systems designer, which is nice. I also wanted to focus on improving myself. I have a lot of experience doing dialogue, but I have less experience with strong plot structuring. Working on this game is helping me improve that part of my toolset."