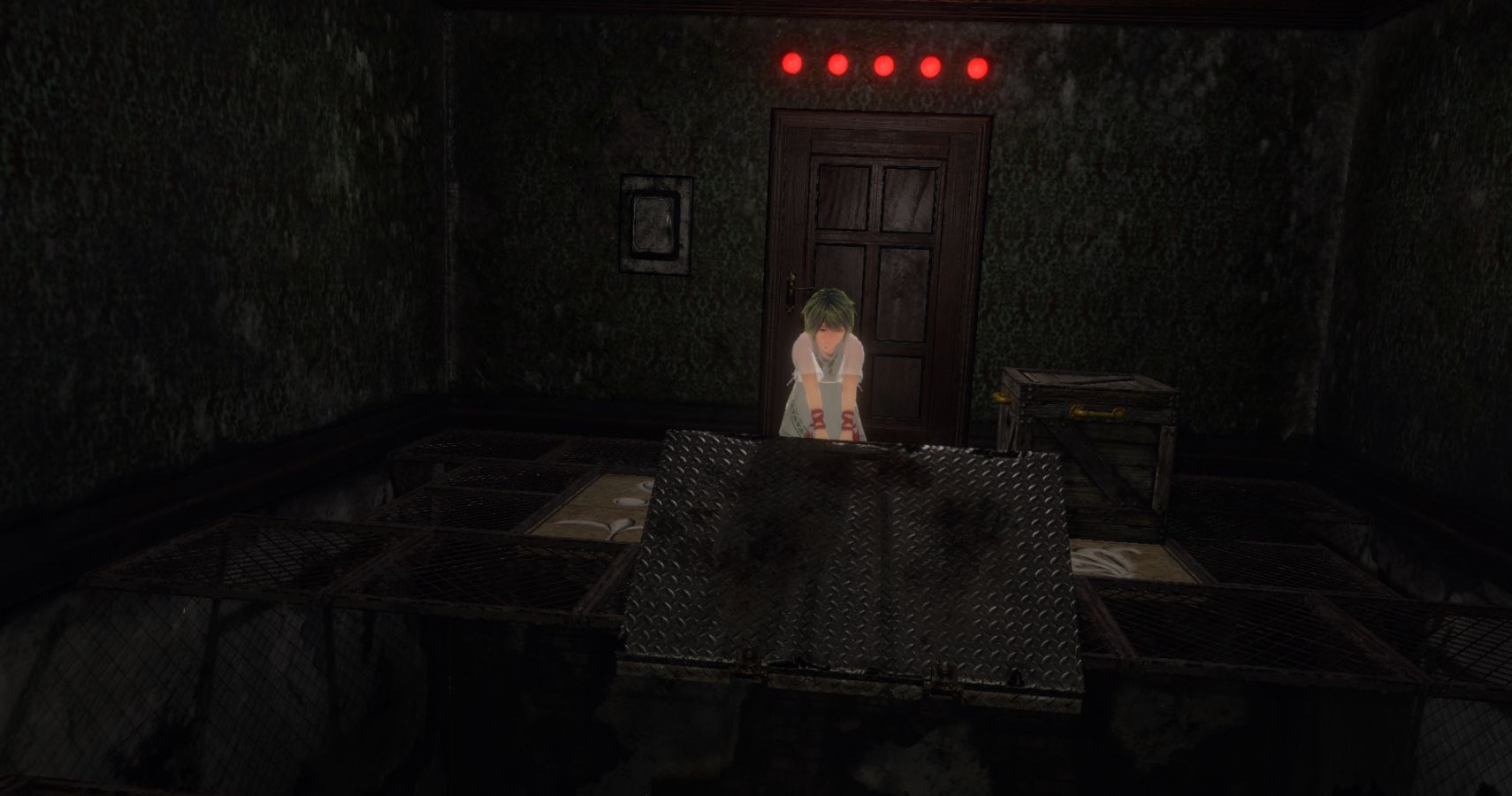

In the first thirty minutes of Last Labyrinth, I watched a child die three times. The first time, she was forced into a pillory and decapitated. The second, she was playing on a beautiful cliffside, only to fall to her death. The third, ground up like beef chuck in spinning columns. Each time, the game gave me just enough space to ruminate on her death before it either offed me or faded to black. And each time, Last Labyrinth continued to intoxicate me with its dreary, wistful blend of whimsy and terror wrapped up in the year’s most audacious VR title.

Disempowerment Fantasy

Last Labyrinth presents players with a simple setup. The unseen player is strapped to a wheelchair, their limbs bound and mouth seemingly gagged. The only thing they can do to communicate with a mysterious little girl is nod and gesture with a laser pointer. Players must guide the child, Katia, through a series of increasingly perilous rooms in hopes of eventual escape. But who are you, exactly? What is Katia to you? And who put you both here?

Last Labyrinth eventually begins to answer these questions in a roundabout sort of way, but not before stripping the player of every last ounce of agency and autonomy. It is, in many ways, the best disempowerment fantasy I’ve experienced in quite a while. When you fail a puzzle, you’re helpless as Katia gets eviscerated and you await your swift and almost certainly painful death. There are no second chances, no ways to escape – you’re boned, plain and simple.

While the puzzles themselves are stellar in and of themselves, the absolute best moments of this game happen when the player and Katia are trapped in a room with a masked assailant. You have mere seconds to guide Katia to a switch, or to use your laser pointer to blind the attacker, before they get their hands on her and choke the life out of her right in front of you. It’s one of the most absolute crushing defeats I’ve felt in a video game, in all my years of experience with the medium. There’s nothing quite like watching a ten-year-old get strangled to death to make you feel like a real piece of garbage.

A Virtually Real Child

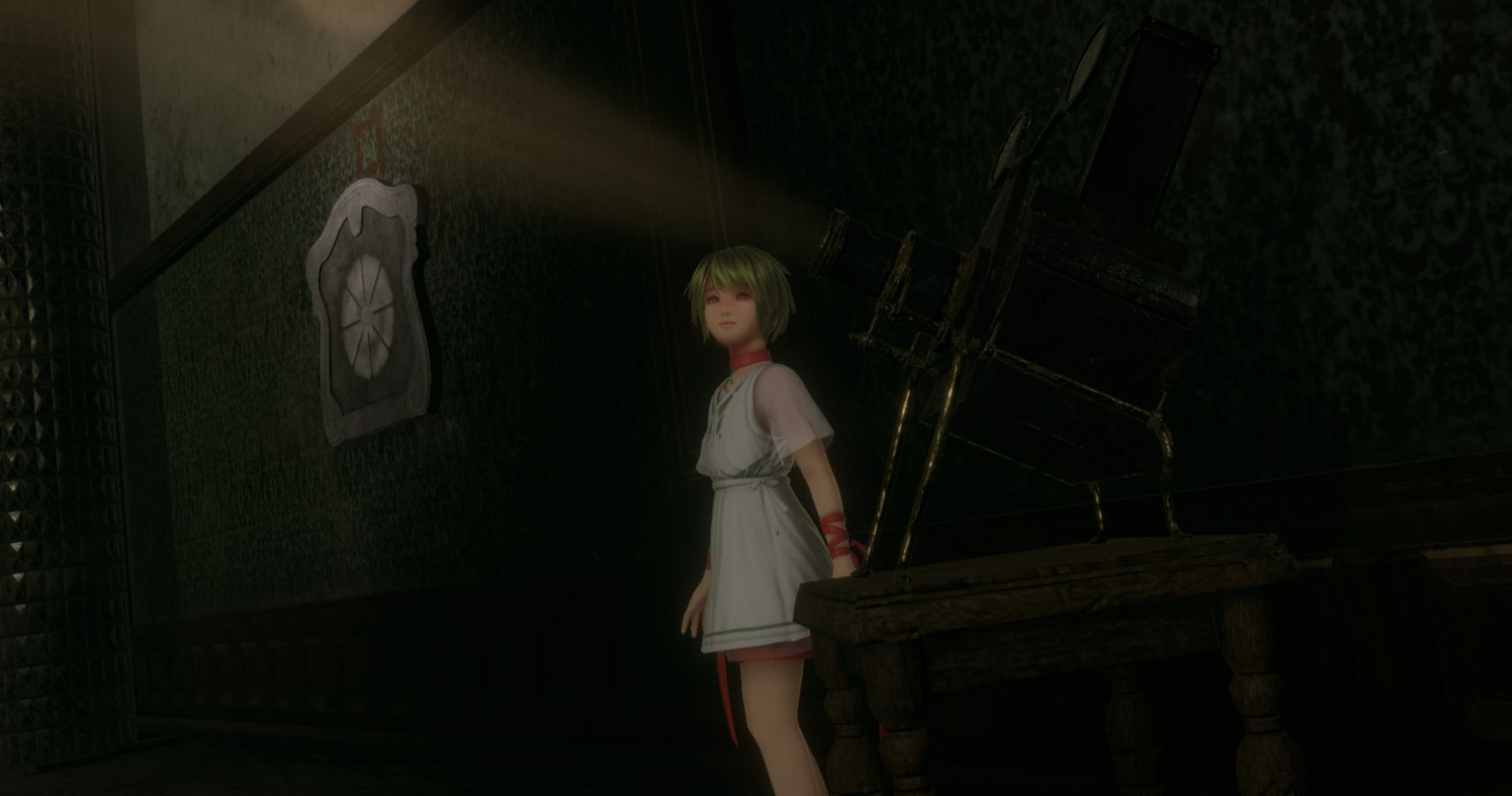

This is largely due to just how well the game gets the player attached to Katia. Much like Yorda in Ico, she communicates in an indecipherable language and gestures to things with her body. It’s up to you to figure out what she wants, how she feels, etc. This results in an organic bond that makes a strong, convincing argument for VR’s existence.

Last Labyrinth and the connection it builds with Katia is something that, frankly, couldn’t be done without the aid of VR. There’s something tangible about her presence, as she learns to trust you a little bit more with each passing hour – her demeanor and mannerisms changing subtly as time goes on. As she smiles at you and carts you around in a wheelchair, you start to feel like that a living, breathing child is in your charge, and every mistake you make feels like a betrayal of her trust.

It was a special kind of hell to have Katia stare into my eyes after being poisoned, cornered by a blade trap, or trying in futility to escape from a large basilisk. When I took my headset off, I felt something that could only be described as guilt eating away at me. I’d failed. I’d failed this small child, and she spent her last moments alive full of terror as a consequence of my own stupidity.

More than Ico, more than Resident Evil 4, more than The Last Of Us, Last Labyrinth nails the idea of being charged with a human life and replicating the overwhelming despair that comes with watching it be dashed against the rocks.

Quite Puzzling

Of course, none of this would mean much of anything if the gameplay weren’t any good. At first, prospects don’t seem great on that front. The initial hour or so serves up some simple puzzles that made me anxious about the trajectory of the game.

“Ah, jeez,” I wondered. “Will all the puzzles be this simple?”

Nope! This game is absolute hell! After you hit the first credit roll (yes, this game very much does the Nier thing,) you’re chipping away at puzzles that feel like Rand Miller’s wettest dreams realized in tangible form – like the Myst creator envisioned dozens of tulpas and they’ve all been made physical and we’re forced to suffer them all. Memorization puzzles, physics puzzles, light math puzzles… Last Labyrinth demands a lot of the player.

Solving a room requires guiding Katia to a button or lever to lock in your answer, as it were, and I’ll be damned if those aren’t some of the most stressful moments in gaming this year. My body broke out in cold sweats as I spent dozens of minutes on some of the later challenges, then locked in my answer and hoped I didn’t completely murder Katia. The game has the audacity, too, to activate a trap sometimes, only to have it fail to kill you and Katia at the last second upon a successful solution. It’s devilish and mean and I love it.

Arthouse, But Make It VR

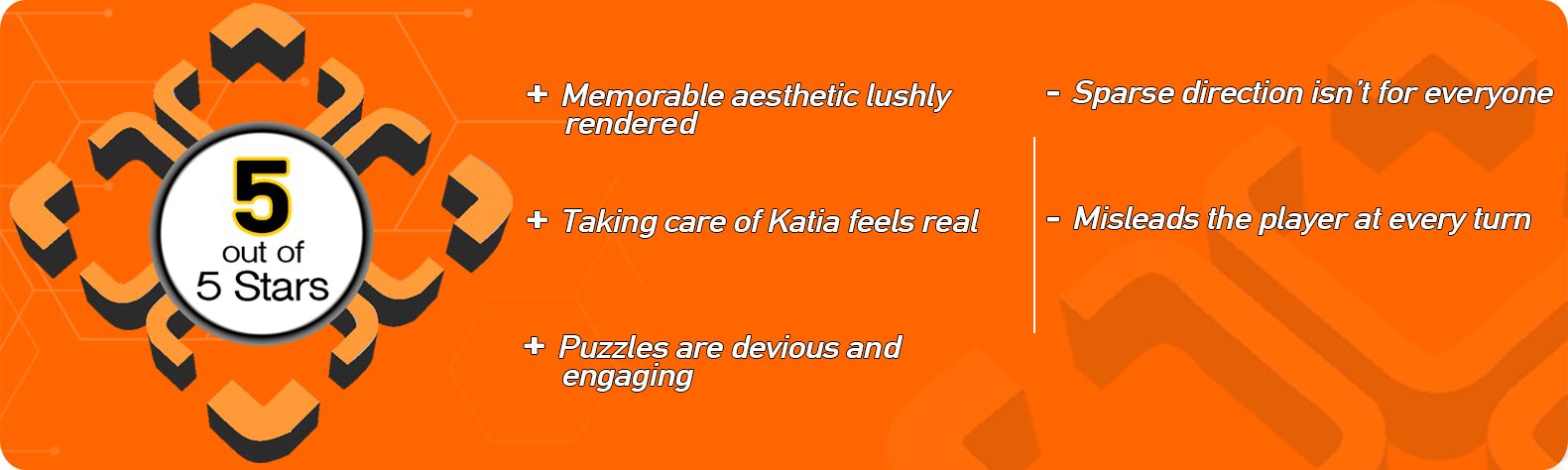

The Quest is my favorite gaming device to come out this year. While there were other games on the platform that were, perhaps, better at giving a dopamine rush and making me feel powerful, none were quite as special as Last Labyrinth. This game check every box for me, with its obfuscated narrative, tight mechanical focus, dreary anime aesthetic, and minimalist musical score. It’s an arthouse game, through and through – the concentrated effort of a group of prolific auteurs, pushing this medium in bold new directions.

Last Labyrinth is a haunting, melancholy work of art held together by a simple premise done remarkably well. Its aesthetics are lush, its mechanics simple but deep, and its core promise of taking care of a virtual child completely delivered on. Irrevocably, it’s one of the titles of 2019, and one of the absolute best things to happen to the medium of VR.

A PC review copy of Last Labyrinth was provided to TheGamer for this review. Last Labyrinth is available now for Oculus Rift, Oculus Quest, PlayStation VR, and Steam.

Last Labyrinth