The faint glimmer of my flashlight only barely illuminates the dereliction around me. As I wander through the police station’s disheveled corridors, it becomes clear that certain places can be simultaneously tranquil and blood-curdling. Perhaps this is why — despite how obvious it is that I am in grave danger in Little Hope — the tantalizing pull into the next dim-lit, potentially perilous room only grows with each step I take toward it.

Assuming control of a young but evidently bright college student named Andrew — who happens to be played by Bandersnatch’s Will Poulter — I am plunged into a world that has fallen victim to harsh obscurity. I quickly learn that I’ve been stranded in a ghost town after a seemingly preternatural bus crash, and that I must work together with my professor and fellow students in order to find a way back to normality.

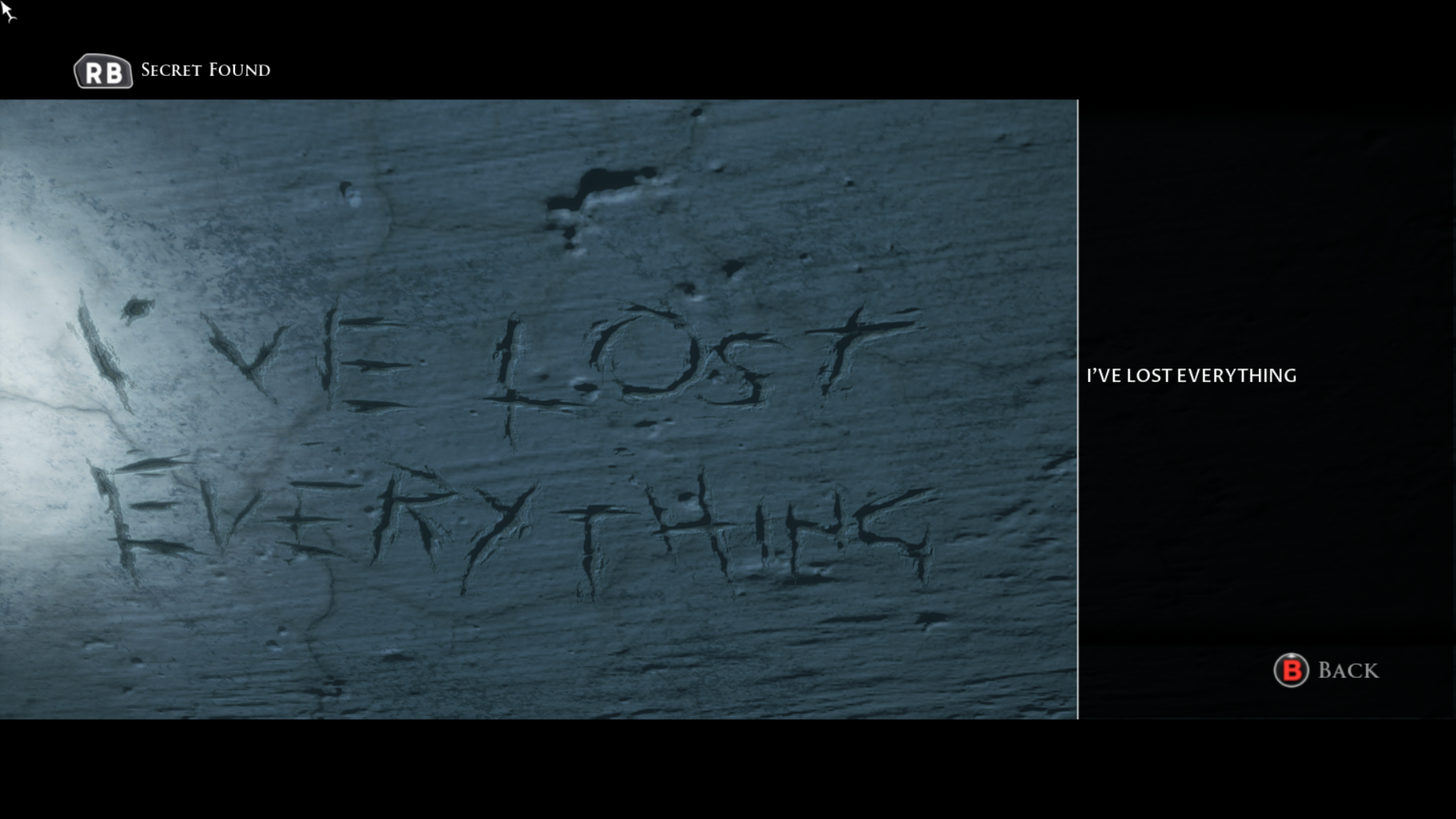

First, we need to find a phone. As I meander around the dilapidated hallways of Little Hope Police Station, I come across various trinkets and ornaments from bygone eras, most of which are coupled with brief, often vague descriptions. The most notable and immediately disconcerting object I discover, though, is a plaque, which serves as a clear indication of what this building was prior to being repurposed as a modern police station: The Old Witches Gaol from the Salem Witch Trials.

Little Hope’s exploration, although rather clunky at first, is deceptively clever. Its top-down perspective’s marriage to fixed camera angles is aesthetically awry, and honestly a bit annoying. However, this annoyance is outweighed by the atmosphere the camera angles create — because you’re unable to see the inside of a room prior to entering it, you’re deprived of the kind of clairvoyance that makes other horror games less scary.

The way you interact with objects is similarly janky, but also similarly practical. I use a controller during my demo, which means that I have to select an object, use the trigger to grip it, and pull the analog in correspondence with any necessary movements to study it. One of the first objects I examine is a defective locker — after slowly opening one of its threadbare drawers, I accidentally snap it, causing its base to cave in, along with my arse. Admittedly, the scare is relatively minor — however, it’s still clearly effective in its attempt to convey the physicality of seemingly insignificant actions in the game.

After eventually stumbling across the predictably necessary phone — which is also predictably unplugged — I set off in search of a cable to reconnect it. After a brief stint wandering around the rest of the station, the phone — still unplugged — begins to ring. Choosing to answer it, I hear the distressed voice of a woman with an accent that is immiscible with the surrounding area. Before I know it I am teleported through space and time, and land in the middle of a town hall several centuries in the past. A woman — with the same voice as the mysterious caller — stands before me, wrongfully accused of being a witch.

The unsettling disparity between confused past and distant present is immediately intriguing. Despite the ostensible absurdity of the narrative, its staunch refusal to offer clarity makes the story compelling — even if you weren’t invested in it until now, it’s difficult to accept something this nonsensical without at least attempting to make sense of it, and so Little Hope at least temporarily wins you over.

Unfortunately this gain in momentum is somewhat tainted by the lack of coherence between characters. Too much of the acting comes across as totally deadpan — although it’s important to note that this isn’t a failing on any of the actor’s individual behalfs so much as it is a lack of natural flow overall. Although the characters converse in a way that makes sense contextually, they rarely sound as if they’re actually talking to one other. Individually, each actor is strong, but the juxtaposition of multiple characters in a single scene often comes across as hodgepodge and mismatched.

None of the characters appear realistically phased by the fact they are involuntarily being transported through time in a dark and deserted ghost town. After returning from the witch’s trial — which, to reiterate, was staged three centuries beforehand — Andrew and his professor are oddly capable of pressing onward without so much as a moment of respite. This would make sense if it was out of necessity, but they come across more like people reading a horror novel than the characters experiencing the events of one.

Despite only playing a 25-minute demo, Little Hope’s narrative genuinely fascinated me. I desperately wanted to know what happened next, having become particularly engrossed in its concept of Doubles — essentially, Andrew and his companions soon realize that the people from the trial look exactly like them, and the events they witness three hundred years in the past have an uncanny influence on the present. It’s mysterious enough to make you curious without being so ambiguous that it becomes completely alienating.

But Little Hope falls down in other areas. On top of the lack of believable conversation, moment-to-moment play is in some ways drastically inferior to cutscenes. While slow, steady exploration works as a result of its juxtaposition of detective-esque investigation and suppressed horror, certain sections of the game are entirely defined by quick-time-events. I found these to be unreliable and unnecessary — despite hammering the X button to open a door, I failed the prompt twice, and on another occasion passed a QTE check when I wasn’t even holding the controller. Admittedly, I have disliked pretty much every instance of quick-time-event mechanics I’ve ever encountered — they feel like a cheap way of gamifying a section of a game that could be substantially more powerful without them, while also erecting massive barriers to accessibility. The QTE prompts in Little Hope were remarkably poor, which is disappointing given its strengths in other departments.

Little Hope is genuinely promising, but remains very clearly a work in progress. With jankily stitched together conversations, a disappointing reliance on quick-time-event mechanics, and some less than convincing performances, it would be easy for me to say I was unenthused by my demo. However, the brave weirdness of its madcap story is captivating, which is further reinforced by its outright refusal to offer exposition. If Little Hope irons out its creases and shifts its weight into the parts it’s actually good at, it could tell a compelling story that’s well worth playing through.