Majora’s Mask has never been my favourite Zelda game. That would be Minish Cap, and yes I know that confession likely means several Zelda fans have already stopped taking me seriously. I also unapologetically adore Twilight Princess, and although Breath of the Wild is excellent, I’m not sure if it would even make my top five. My views on Zelda don’t necessarily align with those of people I know, and that’s fine. But this particular view — that Majora’s Mask remains the most iconic Zelda entry the series has ever known, especially in the year of our lord 2020 — is one that I reckon carries a lot more weight than a hot take.

Majora’s Mask turned 20 years old yesterday, and I firmly believe it’s the masterpiece we have to thank for some of the most Zelda-esque aspects that contemporary Zelda is known for. As a means of celebrating its birthday, Bella wrote an excellent piece on Kafei and Anju, the game’s star-crossed lovers who are unfortunately stricken by a horrid curse. This story — and many of Majora’s Mask’s other stories — is at the heart of what made Majora’s Mask special, and has since served as the blueprint for making Zelda more about the heroic nature of humanity as a self-determined — and self-actionable — concept, as opposed to humanity as an insert plot point that needs to be saved. That is remarkably refreshing, especially in the modern world where cataclysm after catastrophic cataclysm saturates the news with the literal embodiment of “everything happens so much”.

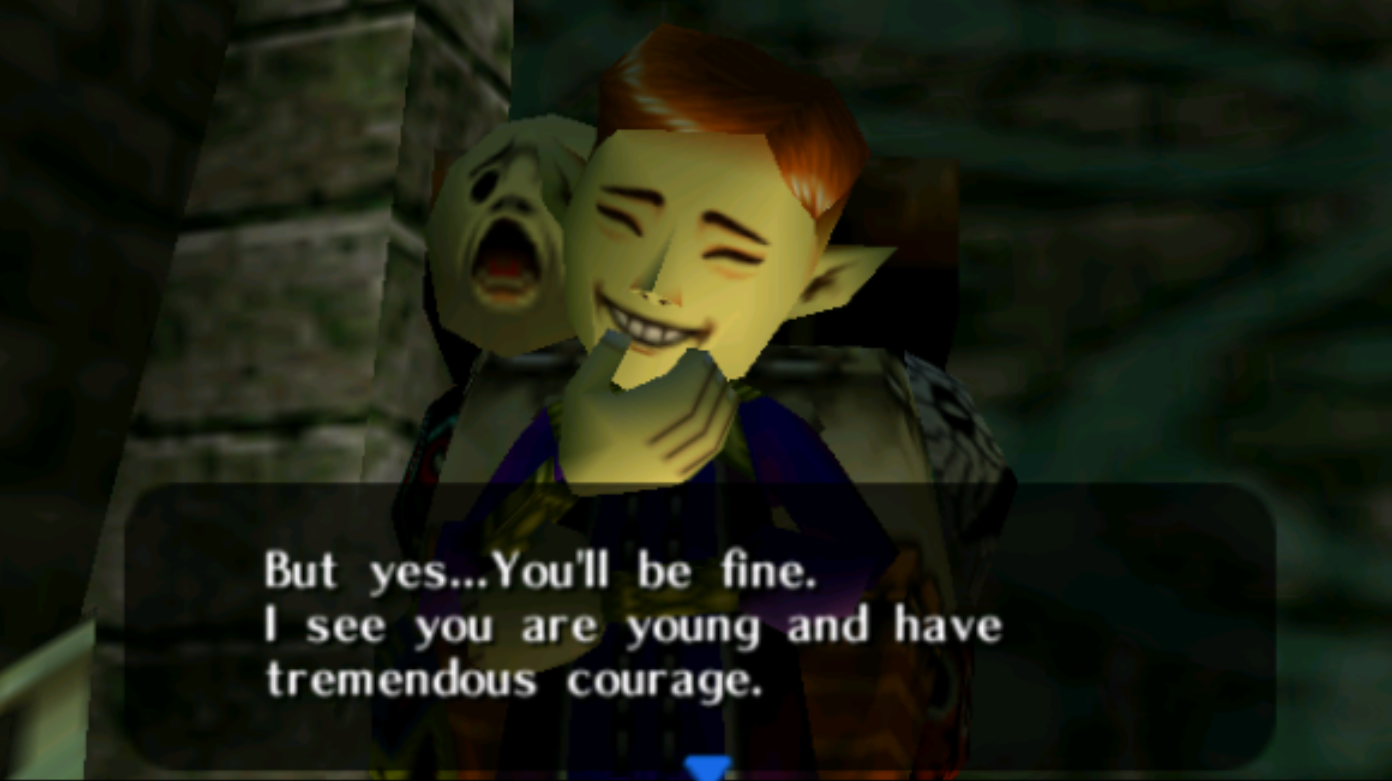

In the piece linked above, Bella discusses how Majora’s Mask makes you genuinely care about the inhabitants of Clock Town. This is one of its greatest strengths — for those unfamiliar with the game, Majora’s Mask sees you constantly repeat a three-day time-loop, gradually learning more about how to stop the encroaching descent of the moon itself. The thing is, the moon is not given the typically grandiose Big Bad status assigned to most major antagonists, nor is nefarious schemer Skull Kid privy to hamfistedly expositional screen time for the sake of it. The vast majority of the game sees you tackling smaller missions, which makes sense given that you’ve only got three days at a time to make a difference in the world. It’s not really about an epic odyssey across the vast expanses of Hyrule, where you forge a level 100 sword after grinding in dungeons for 50 hours. It’s about playing hide-and-seek with five kids who are roughly the same age as you because you want the code to their secret base; chatting to the postman as he makes his daily rounds; and spitting Deku seeds at Tingle’s balloon because his maps are a rip-off and it’s funny to watch him fall. That never gets old.

I mentioned above that Minish Cap is my favourite Zelda game ever — despite its cutesy aesthetic standing in stark contrast to the occasionally grimdark hues of Majora’s Mask, the two games have quite a lot in common. I’m thinking of Rem the shoemaker falling asleep while the Picori handle all of the cobbling; fusing Kinstones with Brocco and Purry in the Hyrule marketplace despite their extortionate prices; and honing your skills as a master swordsman with Swiftblade, who is somehow just as infuriating as he is impressive. It’s a different kind of setup to a lot of other Zelda games, and the majority of other RPGs. It’s not about becoming all-powerful and being the one hero destined to slay the baddie. It boils down to learning about other people and doing everything in your limited power to help them, because you’ve gotten to know them after the last five three-day loops and, actually, they’re pretty nice!

Majora’s Mask is often referred to as one of the darkest entries in Zelda, and for good reason. It’s the direct predecessor to Twilight Princess, and that is quite literally the darkest Zelda game ever made — not just in terms of its narrative, but its actual aesthetic. To this day I regularly rack my brain for a reason as to why Zelda fans seem to enjoy lambasting Twilight Princess as a clownish joke, despite the fact that it has some of the series’ most impressive environmental design and most innovative puzzles. But I digress: this is a piece about Majora’s Mask, and why it’s a lovely Zelda game to return to at this moment in time. Twilight Princess… not so much.

Majora’s Mask, dark as it is, is a much more concentrated effort in the grand scheme of Zelda. It understands worldbuilding better than any other Zelda game to date ever has, constructing its environments from the ground up and populating them with people worth learning about, as opposed to just investing in sheer scale that is peopled for the sake of not being empty. Its strengths in character design, microcosmic storytelling, and actual humor — yes, Zelda used to be funny — are still visible in the series’ DNA, with the primary exception to the rule being Breath of the Wild. As I said at the beginning of this piece, Breath of the Wild is excellent — that is something I would never dream of disputing. For what it’s worth, however, one of my friends once told me that Breath of the Wild is the most impressive tech demo he had ever seen, and I’m inclined to agree. I have tried to play Breath of the Wild three times since the pandemic started and have bounced off of it every time. There is no direction, in my eyes, nor is it easy to obtain any real sense of accomplishment. I could play for ten hours and feel as if I’ve just cooked a few mushrooms. I’m not dismissing that as a bad thing — I’m saying it hasn’t given me any real sense of enjoyment this year.

For all of its technical prowess, Breath of the Wild lacks the same kind of grounded, chaotic, and funny storytelling that was endemic to the raucous streets of Clock Town. That, to me, is what Zelda is all about — I am far more interested in slight nuisance than major calamity, because I have seen 1,000 iterations of the latter and, especially in 2020, it’s nice to be able to compartmentalize your problems in a small little box where they can be easily and readily solved. Majora’s Mask’s three-day loops have been a godsend for me recently, because I feel like I am defeating time itself despite the fact I’m actually just chasing a dog around South Clock Town. Oh no, the timer has ran out and I’m back to square one! Not to worry, because every hour only lasts about 45 seconds and I’ve just spent my time wandering about, learning shortcuts through the city. Every three-day section is less than an hour long, meaning that regardless of whether you solve everything perfectly or just kind of waltz around aimlessly… There’s everything to gain, but not very much to lose. You either move on to the next part or do this same one again — if anything this just optimizes your runs, because now you know exactly what to do and you don’t have to wait very long to do it.

Majora’s Mask defined some of the best and most human parts of every Zelda game that has come to pass since its launch this time 20 years ago. It’s funny to think that now, its most innovative and unique gimmick is what makes it particularly resonant and satisfying in 2020.