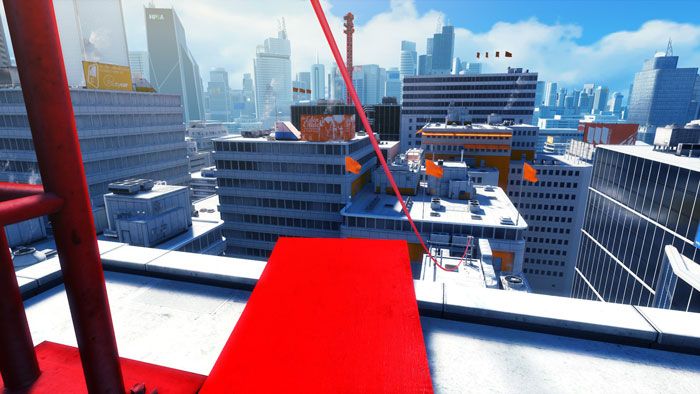

All around you fragments of the crumbling bridge cascade into the roaring ocean, but there is a way to escape without plummeting into the waves below. A brief look at your surroundings will show you that a route through the maelstrom is clearly outlined in an electrifying red — this all feels strangely familiar.

The opening section to Marvel's Avengers sees you swiftly jump from hero to hero as a means of introducing you to each character in its roster. The drastic differences in their distinct combat abilities are immediately evident — while Thor resembles the iteration of Kratos we saw in God of War (2018), Iron Man feels more like a character from Anthem or Warframe, whereas Black Widow's kit resembles the kind of style you'd expect to encounter in a Splinter Cell game if Sam Fisher stopped caring about stealth.

But despite the ways in which Marvel's Avengers distinguishes its heroes from one another, one element of its rip-roaring introduction unites the experiences of playing each and every one of them together. And although it's not the first game to implement it since Mirror's Edge — nor will it be the last — it feels particularly prominent here, to the extent that it quickly establishes itself a significant reason for why moment-to-moment play in Marvel's Avengers actually succeeds.

For those unacquainted with Mirror's Edge, it's a parkour game set in a dystopian society where oppressors maintain order by controlling the media and suppressing its citizens. You play as Faith, a member of the dissident Runners who traverse the city's upper levels in order to covertly transfer sensitive information.

Although Mirror's Edge features some combat, it pales in comparison to the game's emphasis on free mobility. From wall-running to pop-vaulting, Faith is capable of springboarding her way across even the most precarious obstacle courses — provided they are almost brazenly marked by a stark, dazzling crimson.

It's important to note that plenty of other games use colour to illustrate structures that can be interacted with. The Last of Us Part 2's climbable objects are marked as yellow, and even indies like Spirifarer use light to demonstrate which parts of a building's interior can be traversed. Other games use smaller objects to indicate that a larger structure is significant — for example, high areas worth climbing to in Far Cry will usually have a rope suspended from a lofty precipice. But Mirror's Edge takes this premise to whole new heights — it prides itself on speed and style, and so its environmental signifiers are much more than mere level design tricks.

When you play a superhero game, it's important to feel as if you are emphatically in control of that superhero, and that control begets an inherent sense of power. If The Incredible Hulk can't pick up a tank and mill it 50 metres across the map, the game isn't accomplishing what it needs to — the best thing about games like Marvel's Spider-Man and the Batman: Arkham series is that they intentionally and aggressively lean into what makes their protagonists unique.

So, the aforementioned distinctions in Marvel's Avengers combat design are a hugely important aspect of what makes the game work. I love playing as Thor and am relatively non-plussed about Black Widow's design. In my eyes, both of those statements are positive, because being able to like and dislike different aspects of a game is indicative of the fact that they are fundamentally different.

But these differences, while intriguing, are not what makes Marvel's Avengers work for me. The reason I am enjoying my time with Marvel's Avengers — and why I can't wait to dive back in this evening — is because of its mobility design. More specifically, I'm interested in the mobility prompts sporadically dotted across the game's surprisingly spacious maps.

As you can see in the screenshot above, Hulk is beelining his way towards a red ramp. Behind the ramp, in the background, is a red truck — you can't see it particularly well in a still shot, but the trailer is marked with distinctive white scratches, denoting its status as a surface Hulk is able to springboard himself off of mid-jump.

Now, this section is admittedly quite linear — it has nothing on the environments that come after and is defined by the atmosphere of urgency derived from having to vacate the rapidly deteriorating bridge. However, it serves as an excellent case study in terms of how level design can cleverly inform momentum.

Some games hit you with quick-time-event prompts, meaning that as you approach a ledge you'll receive a cue telling you, "Press X to jump." Outside of tutorials, this is almost obnoxiously detrimental to immersion. Other games allow you to determine the probability of successfully executing a jump simply by observing the gap and making an educated decision. While this is better than relying on QTE, it drastically inhibits what I mentioned above: momentum.

The single best thing Mirror's Edge ever did was map its mobility in color and structure — red ramps, red ziplines, red springboards, and red walls. Even without the color, the sprites for each of these objects — while distinctive enough for variety in environmental design — were so immediately striking that you could leap across an abyssal chasm between two skyscrapers without even recognizing what you were doing. Simply adding a small ramp to the edge of a building — which, given that Mirror's Edge's Runners had constructed their own secret trails high above the dystopian metropolis below, actually made narrative sense — completely changed how you moved. To this day, Mirror's Edge is the most shockingly ahead-of-its-time game I've ever played.

So it makes sense that, 12 years later, Marvel's Avengers would take a leaf out of its book and map the mobility of its environments. Whether you're playing as Miss Marvel or Black Widow, vertical progression is almost always marked by red ramps, walls, and grappling points. It's a perfect implementation of an unnatural object into a space that is desperately trying to pose as natural. Similarly to how you could read a sentence with half the letters all jumbled up, these immediately noticeable structures are something you register as you go through the motions — they serve as a prompt that you can instantly respond to without resorting to clunky text cues or freeze frames, and as result, they will never directly slow you down.

And so you can bolt, bound, and burst your way through levels in Marvel's Avengers while moving at the same pace as an actual superhero. There's no weighing up the precariousness of a jump, nor are there any overbearing tutorial messages that force you to drop from 100 to zero at the crux of a wild, upward dash. The reason levels in Marvel's Avengers are well-paced — importantly, when they are well-paced — is largely because they drew on a technique from 12 years ago that, to this day, has yet to age out of style.

That's another good thing that comes from adding red ramps into your game — they're pretty nice to look at.