Before its original launch back in 2010, BioWare described Mass Effect 2 as its Empire Strikes Back. In the years since the film’s release, it has become shorthand for a dark, foreboding middle chapter that aims to subvert everything that came before it. A New Hope was a whimsical journey into a new world filled with lovable new characters, and there was seldom any doubt that the heroes wouldn’t emerge victorious. They suffer loss and adversity along the way, but they inevitably triumph, smiling in the closing moments as the universe celebrates them as infallible forces of good. Empire takes all that and cuts it to pieces with a crimson lightsaber.

Mass Effect was much the same. Whether your Commander Shepard was Paragon or Renegade - they defeat Saren, they destroy Sovereign, and the galaxy looks at them as an almost biblical saviour who came along and fought back against evil when nobody else could. In the closing moments, our hero is feared dead, Captain Anderson peering through the Citadel wreckage with a grimace while tending to your squadmates. When all seems lost, Shepard sprints out of the wreckage with a grin, posing for the camera like an obnoxious twat as the screen fades to black.

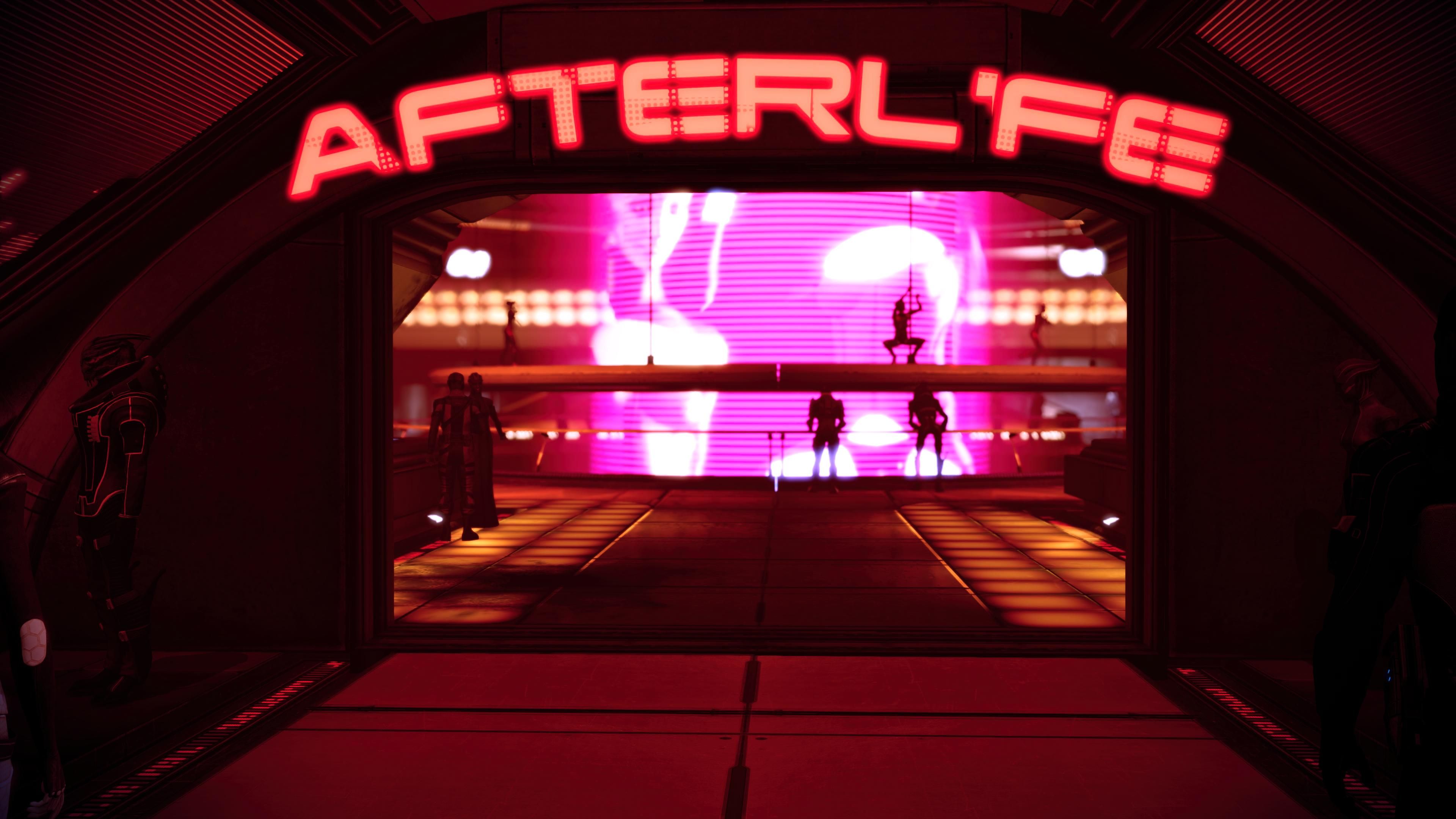

They’re almost mocking Anderson for even entertaining the thought that a mere Reaper could take them down. Ironic, when you think about how the sequel begins. Mass Effect 2 is an immediate subversion of the grand sense of discovery that defined its predecessor. The galaxy has been established as a fascinating yet unforgiving place, so now it’s time to delve into the seedier underbelly, analysing the exact ways in which its myriad races and political systems operate and oftentimes take advantage of those most vulnerable. This all begins with Shepard’s death, both a symbolic and literal rebirth of the franchise that morphs its neon blue tones of optimism into a blorange palette of death and uncertainty.

Awakened by Cerberus, Shepard is greeted with a changed world. Two years have passed, and the newfound expression of determination born from Sovereign’s defeat has dwindled into an anxious malaise. The Reaper threat has been sidelined by galactic bureaucracy, with everything we fought for in the previous game being left behind in favour of the status quo, our crew splintered across the verse as without a leader, they have little reason to remain. It’s our job to bring them back together, even if at times it feels like we’re tearing them away from causes even greater than our own. Shepard is fully aware that they’re recruiting for a suicide mission, an endeavour with minimal planning and no guarantee of success. In the opening hours, we have no idea if we can even fight the Collectors, let alone deal with the sinister threat ruling over them. All we can do is keep moving forward.

This brings me back to other darker middle chapters across popular culture. Empire Strikes Back, Captain America: The Winter Soldier, The Dark Knight - these are all sequels that aim to destabilize everything we’ve come to learn about their themes, worlds, and characters. Their progenitors provide a level of comfort, an aura of familiarity that holds our hand tightly and refuses to let go. Even as I played through the original Mass Effect for the first time in over a decade, it felt like reuniting with an old friend, one whose habits have remained stringent regardless of my absence. Sure, they’ve spruced themselves up a bit, but the core experience remains the same. I was safe, knowing that the struggles ahead can be overcome if I simply made the right decisions and relied on my crew when it really mattered.

Mass Effect 2 immediately abandons this futuristic idealism. Shepard is now working with Cerberus, an organisation despised across the galaxy and one they themselves have trouble agreeing with. Despite all this, Cerberus is the only one recognising the true threat before humanity, and soon, the entire galaxy. I’m reluctant, but I begin recruiting my old comrades under a new banner, informing them of the precarious waters that await us with the utmost honesty. Together, we march forward into the suicide mission praying that we all make it out alive. Depending on my own decisions, some will live and others will die, and I’ll have to deal with the consequences of such things as I venture into the trilogy’s final chapter.

I imagine that creators, whether they be game developers or film directors, view the dark middle chapter as a way to challenge themselves. In BioWare’s case, it spent years creating an ambitious new universe with its own established rules and branching lore, so Mass Effect 2 provided an opportunity to subvert its own creation, to grow the universe into something tangibly different yet equally as dense. Opening acts are traditionally accompanied by innocent optimism, a hopeful declaration of imagination with those behind it wishing for the greatest levels of success. Once that recognition and security had been garnered, BioWare was safe to test the waters, even if it meant fundamentally altering the core tenets that helped define it in the first place.

Mass Effect 2 does exactly this, which explains why it is often hailed as undeniably superior or a pale imitator of what came before it. Both opinions are perfectly valid, and likely a consequence of what we as players, viewers, and readers look for in a fictional universe. I don’t mind delving into the darkness if I’m rewarded with meaningful stories and a personal connection to my favourite locations and characters - which the sequel executes upon perfectly. The first game is more conventional, more predictable, yet it had to be in order to establish the brilliance of its universe and how it would continue to grow in all manner of mediums for years to come. It also came out in 2007, so certain design decisions are much easier to forgive with the power of hindsight at our disposal.

Dark middle chapters are a reward for creators and consumers alike, a new take on a property that has earned its success, and a right to try something different even if it alienates those who provided such opportunities to begin with. They have since morphed into tired cliches, but it’s important to look past the edgier atmosphere and colour profile to gaze at what sits in the centre - since it will almost always surprise you.