The setup in Fallout: New Vegas is perfect. After being betrayed and shot in the head, you wake up in the sleepy little desert town of Goodsprings, mysteriously alive, and embark on a quest for revenge—if you want to. There's no long-winded vault sequence, no complicated preamble. You talk to a local doctor who managed to yank the bullet out of your skull, then you're set free in the Mojave Wasteland and left to your own devices. Obsidian knows you're eager to start your adventure and spends as little time as possible holding you back from it.

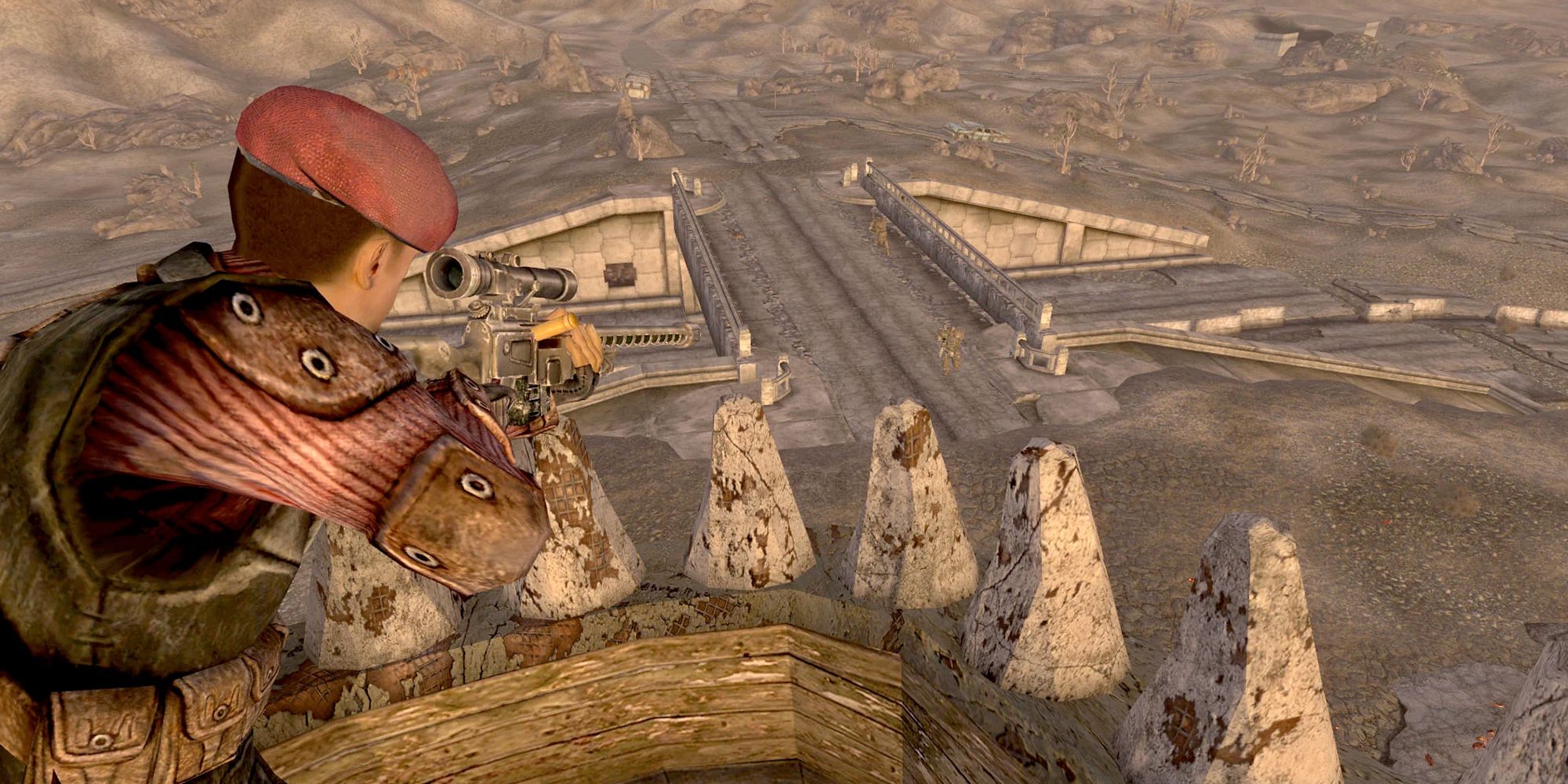

You wander into the desert, the archetypal Western drifter, and the vibrancy of the place immediately hits you. Fallout 3's Capital Wasteland was a concrete desert of shattered buildings and twisted metal surrounded by irradiated scrubland. A wasteland in the truest sense. But the Mojave, having avoided the worst of the nuclear war that ravaged North America in Fallout's alternate timeline, is vibrant, colourful, and—in the case of the New Vegas strip—surprisingly intact. It's still desolate and post-apocalyptic, but not as bleakly hopeless.

As you travel across the Mojave, completing jobs, meeting people, siding with factions (or not), and generally making a name for yourself, the reputation system comes into play. In Fallout 3 your character was defined by a binary karma system, making them either Hitler or Jesus. New Vegas, on the other hand, made your reputation more important than some arbitrary moral swing-o-meter. Karma was still there, it just wasn't as important. Becoming allies or enemies with the Mojave's many powerful factions was more important—and useful.

Pal around with the Brotherhood of Steel and you'd get access to their safehouse, along with a regularly replenished stockpile of energy weapons and ammunition. Piss them off and Veronica, one of the game's best companions, would refuse to join you. This is something Obsidian has always been great at, and would take to new extremes in the superb Pillars of Eternity series. This extra layer of reactivity made New Vegas a more satisfying, nuanced role-playing game than Fallout 3, which pivoted entirely around players being 'good' or 'evil'.

This nuance also extended to the quest design. Obsidian understood that the most interesting choices in video games are the ones where there are bad and good sides to them. There was hardly anything as blunt as blowing up Megaton or not blowing up Megaton in New Vegas. The morality was greyer, and the outcome of your decisions was rarely what you expected. Again, this made it a better RPG than Fallout 3, whose moral quandaries were, in general, much less sophisticated. Obsidian challenged you and your character on a deeper level.

There really is no question that New Vegas is the best Bethesda-era Fallout game. The companions were rich, interesting characters, not just mindless drones who followed you around blindly. Obsidian understood Fallout's deep lore in a way Bethesda has never managed. All the things that were bad about it—the jank, the dead-eyed character models, the lifeless cities—were a result of the creaky old engine the developer inherited. I don't know if Obsidian will ever make a follow-up, but after the deeply shallow Fallout 4 we need it more than ever.