Pentiment, the wonderful new adventure game from Obsidian, incorporates a feature that I've loved since I first saw it introduced a few years ago.

In Pyre, Supergiant Games added hyperlinks to in-game text so that, if you saw a term you didn't recognize, you could hover over it to read the definition. That game's setting was fantastical, so this was a way to keep the dialogue natural — avoiding expository lines like, "Well, President Roosevelt, we've been at war with Germany for two years now" — while still communicating all the necessary background information to the audience. It's like the commentaries Valve includes in some of its games, which allow you to hear the background information on certain aspects of development. But, instead of learning the history of the making of the game, you're learning the history of its world.

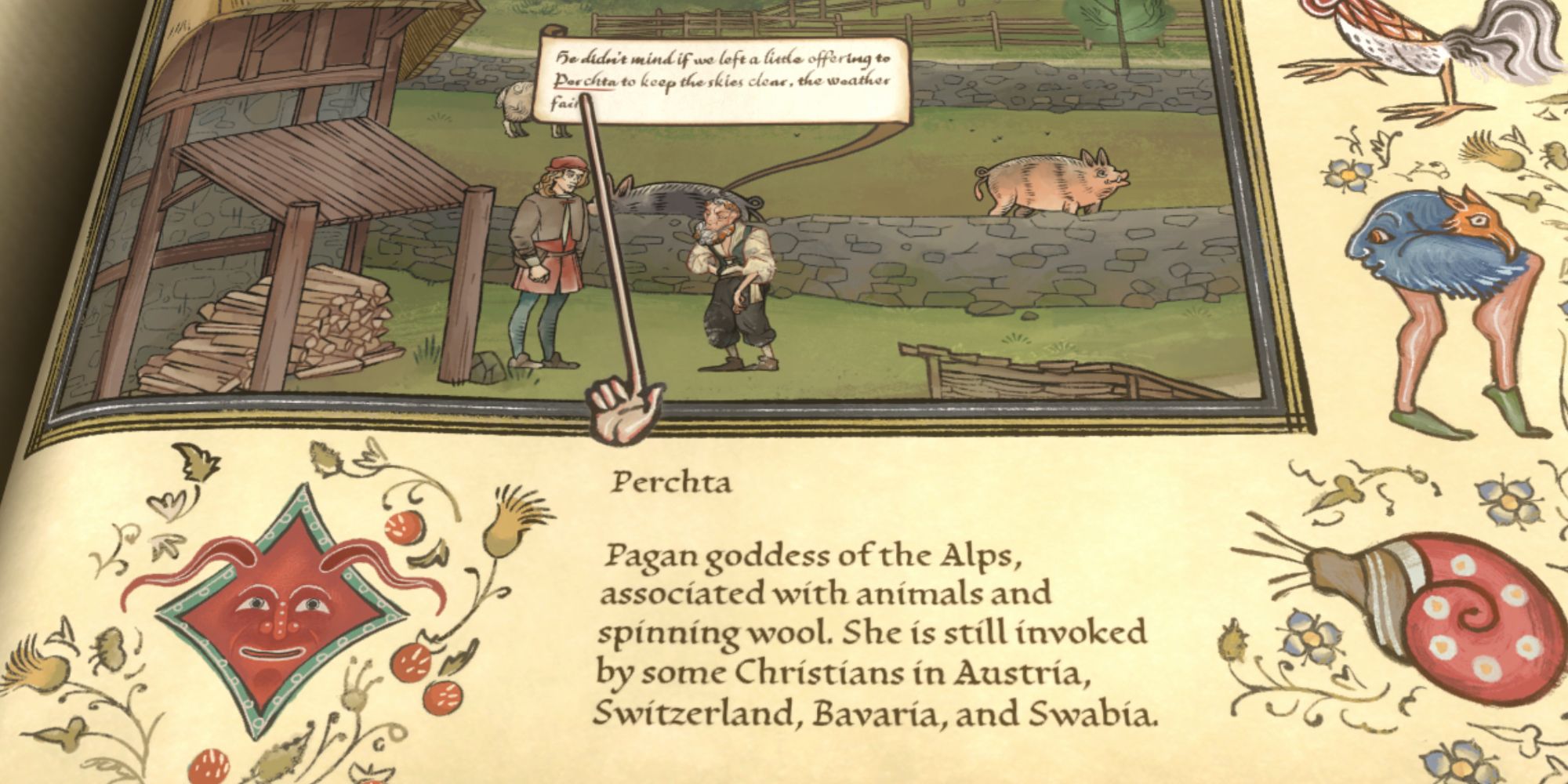

Pentiment does this too, though, fittingly, it presents this background information as marginalia, scrawled in the white space around the screen. If a character uses a term that is no longer used outside of its historical context — like "diet" to refer to a formal deliberative meeting of the Holy Roman Empire — you can click on the word, the camera zooms out to show you the screen as a picture in an illuminated manuscript, and read the quill-written definition. Pentiment does the same for locations that have a different significance in the medieval era. Florence is a different place in our cultural understanding in 2022 than it was in 1518, and Pentiment's glossary helps to quickly explain the realities of its era.

The game, as a whole, makes real medieval history as interesting and full of intrigue as fantasy. Though I've always enjoyed stories that take place in fantastical versions of the Middle Ages, like Game of Thrones and The Lord of the Rings, I've always struggled to find the actual real medieval era interesting. I love Obsidian games and Pentiment looked like my kind of game, gameplay-wise, but the setting didn't do much for me when it was announced. But, after playing several hours of the game, I feel as invested in this world as I ever did in the sci-fi setting of Obsidian's last RPG, The Outer Worlds.

In part, that's because Pentiment treats its medieval setting in the same way good RPGs treat their fantasy or sci-fi worlds. In the chunk of the game I've played so far, all the action has been confined to Tassing and the neighboring Keirsau Abbey, a monastic church perched on a hill above the Bavarian town. When you encounter references to Nuremberg or Rome, it isn't because those places will eventually become especially significant to the events in Tassing, or because Andreas will travel to visit them. (I assume; I'm only about five hours in). Instead, Pentiment weaves in references to the people and places outside Tassing because they help to give us a fuller sense of the world.

Even if I had never left the small town where I grew up, my life would still be impacted by the world outside it. Like Luke Skywalker on Tatooine, or Jon Snow in Winterfell, or Frodo in the Shire, Pentiment's Andreas knows about the world beyond his current home, and that knowledge — represented by several backgrounds you can choose for Andreas — informs how he interacts with the people he meets in Tassing. The references, then, feel like the background cities that parallax scroll past while Sonic the Hedgehog speeds by. The game doesn't need to let you visit them for them to make the world feel bigger.