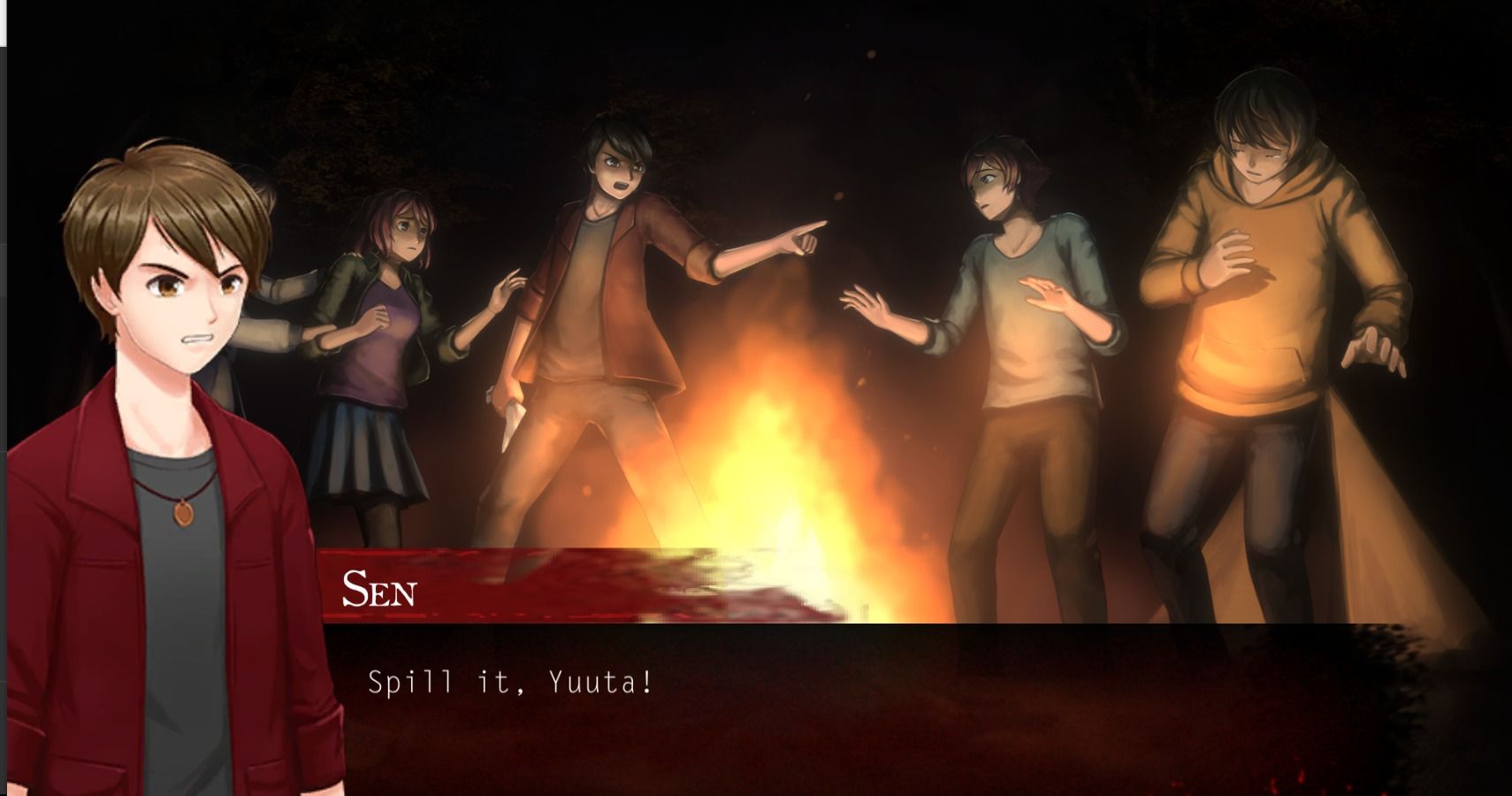

Re:Turn - One Way Trip is an upcoming horror indie boasting a retro, pixel art aesthetic. Based on classic Japanese horror films, it sees a young girl, Saki, go on an ostensibly ordinary camping trip with her friends. As with most horror, however, things quickly take a turn for the worst, and Saki somehow ends up on a dilapidated train stationed in a mysterious forest.

But this is not as generically stereotypical as it might seem — the train itself exists in two alternate realities, or timelines, which directly affect one another, and is surrounded by massive, amphibious eyes, and a monster that looks a bit like the animated version of Bloodborne’s Cleric Beast.

Re:Turn’s horror is slow and potent. There are no jump scares, from what I played, nor any overtly gory aesthetics designed to pull screams without substance. It moves forward at a snail’s pace, and therefore sustains a faint but ever-present degree of suspense.

“It started with addressing pacing the way you’d do with any story,” Re:Turn writer David Bergantino explains. An established horror writer, Bergantino has worked with everyone from Clive Barker, to M Night Shyamalan, to Neil Gaiman, and is currently hard at work on Techland’s upcoming Dying Light 2.

According to Bergantino, the most important elements of pacing to focus on were, "things as simple [as] varying the lengths of chapters, to alternating tones from scary to emotional to humorous, to going from more expositional sections of the game to more action-driven sequences and back.” He notes that the puzzles in Re:Turn not only vary in difficulty, form, and scope, but also in terms of where they appear in the story, how they are woven into the wider narrative, and which section of the game’s train — in both the past and present — they occupy.

“The goal was to make the unavoidable need to walk back and forth across the same, limited geography interesting and not tedious or too repetitive,” Bergantino says. “All this found me switching from micro-mode — the writing and designing — to macro mode: seeing it all from above, seeing the ‘shape’ it all took, then reaching down and rearranging pieces, tugging on some ends to stretch them out, tucking a few places in to make things shorter and sweeter.”

This is probably why many of the game’s puzzles play with time manipulation. In order to unlock a bin in the present, for example, Saki must find an iron ball in the past, before returning to the present and using it to complete a puzzle. And because the game is so emphatically linear, you are constantly bouncing between two timelines in a structured and regimented way — which is why Bergantino and his team often thought, “too slow,” “too fast,” “not scary enough.” Bergantino needed perspectives from people who didn’t have the benefit — or “terror,” as he puts it — of seeing what’s inside his head.

“And out of that, we hope, comes a game that invites players to come along on a journey and entertains them enough that they stay for the whole thing,” he explains.

There are two elements that make a 2D side-scroller like Re:Turn so effective at evoking an atmosphere steeped in fear and ambiguity: art and audio. According to Bergantino, the decision to go with a retro, pixel art style allows the team to convert limitations into strengths — pixel art may be simplistic in the eyes of some people, but to Bergantino it’s “gorgeous and able to create compelling environments and moods.

“However, it doesn’t overwork like photo-realistic console games — not that I don’t enjoy them. But it’s the difference between reading a book and then seeing a film based on that book — even if it’s a good movie, it’s still different than the movie your imagination created while reading.”

By this logic, Bergantino argues, there’s much more room for imagination if a game uses a distinct and ostensibly simple art style as opposed to one devoted entirely to pursuing realism. “The style makes the player a ‘partner’ in the experience,” he explains. “What shows on the screen becomes only the tip of the iceberg of the visuals, the rest of which take place in the player’s imagination.

“And of course, this style and the overall format of this game, makes it perfect for storytelling in a more “literary” sense,” he adds. “I don’t have to write cinematically — all action, camera angles and such. I can focus on the meat of a story like a novel; words rather than the sweeping and expensive visuals you’d find in a motion picture or high-end console game.”

These visuals lend themselves well to Re:Turn’s influences, which, according to Bergantino, are predominantly films such as The Ring, The Grudge, Pulse, The Eye, and others from that era of Japanese horror.

“Human protagonists face some sort of lingering force, usually emotionally based — rage, fear, sadness — which in turn forces them to face their own related issues,” he explains. “In addition, there’s usually some sort of twist. Especially in a movie like The Eye, you are led to believe one thing and then discover what’s going on is something entirely different. I wanted to start in a ‘typical’ place, including the settings and the characters and style of story… then take it somewhere else you might not expect.

“Everything in the game, with perhaps the exception of the maze puzzle, is based on something from Japanese culture. And while there are of course some creative liberties taken for the sake of storytelling or puzzle design, every item in the game is grounded or at least initially presented in its real-world context. We didn’t just go ‘oooo… that doll looks cool’ and disregard what that doll represented in Japanese culture.” Bergantino adds that this also accounts for the game’s use of alternate realities — in his eyes, it was only natural to include a past version of the current landscape in a game influenced by the kind of stories Re:Turn is interested in.

The other element mentioned above is audio design, which Re:Turn uses to create a harrowing sense of dread without having to accelerate its plot or wrench its visuals into a state of sensory overload. “I believe Re:Turn has a unique mix of scares and relatable emotion,” Bergantino says. “Other games of its kind can be relentlessly terrifying and gory. Nothing wrong with that of course, but I’d like to think we’ll stand out for delivering something that is more textured and nuanced, while still being legit scary.

“Audio design is critical [for this],” he adds. “It’s doubly critical for horror, and especially low-budget horror — film or game. You can accomplish so much with sounds and use them to plug directly into a player’s imagination. From a budget perspective, sounds are way cheaper to produce than visual assets. Especially with a game like this, with its glorious limitations, sounds play a huge role in bridging the gap between what a player sees and what dances around in the back corners of his or her mind.

“We spent a lot of time on this. I’m pretty sure I drove the team crazy because I wanted to sound design a pixel art game like it was a Spielberg film. We spent hours tossing sound reference back and forth until we found just the right sounds.”

This, together with the pixel art style, creates the cohesive whole that helps Re:Turn to succeed as a horror game. As Bergantino says, he can write, but without programming, and art, and audio design, he’s essentially writing a book, as opposed to helping to develop a video game. And in developing said game, as a means of attempting to present the “Dave” version of a story in this genre, Bergantino has managed to create something that is both scary and sincere, while being effective in its own, individual way.

“I’ll just be happy if its ‘impact’ results in a few players saying, ‘Hey, that was pretty good!’” Bergantino says. “As for the rest of Re:Turn, well, I just hope people get attached to Saki, the main character, and relate to her journey.”