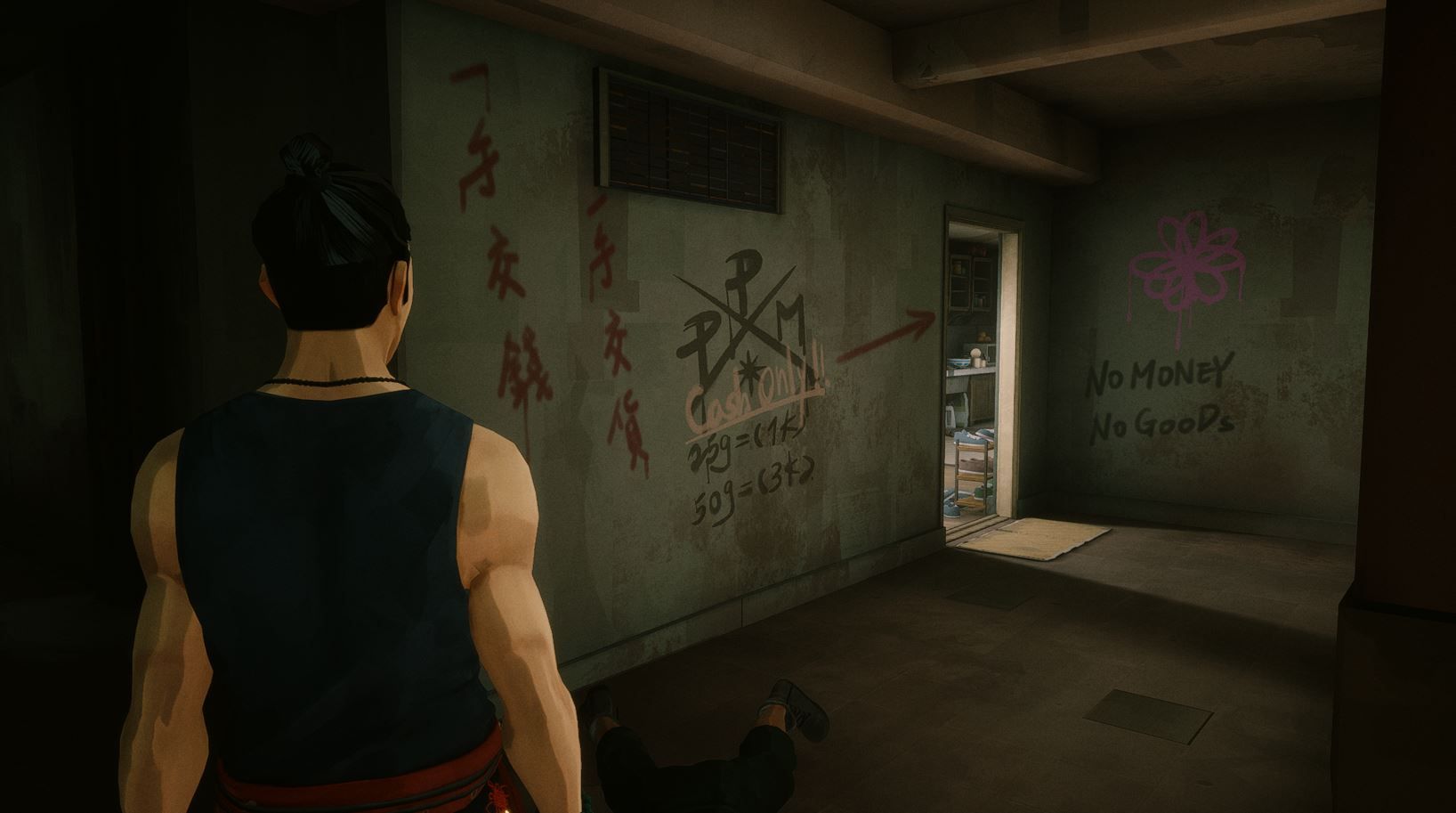

In between bouts of Sifu’s ferocious brawling, there’s a scene I can’t help but keep thinking about: a particular graffiti that was hastily drawn on a wall, presumably by a local drug dealer. It’s a Chinese phrase that says “一手交钱, 一手交货” which, when loosely translated, means “give me the money and I’ll give you the goods”. But next to it is an inexplicable decision to also include an English translation of that very phrase, “No money no goods”, as if the drug peddler has the foresight to consider entertaining English-speaking or international junkies who may just be dropping by the local illegal pharmacy to pick up some good ol’ fashioned drugs. I mean, good thinking, buddy.

Make no mistake; such emblems and other icons of Chinese culture are merely an aesthetic in Sifu, used to pepper in a little flair, and to sprinkle a little bit of exoticism in this kungfu brawler. I can name a few examples of the game’s egregious use of Chinese signifiers: take for instance the game’s icon, a replica of a red stamp that is imprinted with a Chinese seal, which is inscribed with the Chinese characters 'sifu' (if you have, till now, no idea what ‘sifu’, as in '师父', is, it means ‘teacher’ or ‘master’. Fun fact: ‘sifu’, as in '师傅', can also be used to address cab drivers, skilled tradespeople, monks and priests). It’s a pretty frivolous use of the stamp, given that these seals are typically etched with personal names rather than titles, and used as signatures to sign off personal or official documents. Then there are the game’s menus, with UI design choices that are wildly inconsistent; some buttons and words are accompanied by a sometimes incorrectly translated Chinese phrase, and some without (the word ‘loading’ by the Chinese equivalent, but the word ‘start' is not). Then there’s the option for you to return to what the game refers to as your 'wuguan'—the training hall where you return to in between levels—which is odd because you can simply just say ‘training hall’ rather than ‘wuguan’.

Take away all these motifs and Chinese vignettes—the distinctly Chinese backdrop, the training hall, the Chinese words and even the mahjong tiles littered around—and the core of the game will still be the same. That’s because the revenge tale that Sifu is weaving isn’t intrinsically Chinese, unlike that of The Legend of Tianding, which is about the exploits of Taiwanese folk hero Liao Tianding. Nor is it Shadowrun: Hong Kong, one of the best cyberpunk games that takes into consideration the socioeconomic circumstances in the country that it took liberal cues from. Instead, Chineseness in Sifu is reduced to a mere palette swap; you can easily replace the protagonist with, say, John Wick, and Sifu will still be the same fighting game underneath it all.

But is Sifu fun? Is the game mechanically sound? Do the punches feel weighty and good, and will you feel like a badass taking down dozens of Chinese mobsters in a tight corridor, à la the much-talked about fight scene from action thriller Oldboy? Does the game challenge you to be a more skilled Gamer? In my colleague George Foster’s in-depth review of the game’s mechanics and playability, he found himself loving it, which is brilliant. I, too, had fun with Sifu at times; the fights are brutal, and its combat pulses harmoniously to the beat of the game’s backing tracks, especially when you manage to execute your punches and parries well. But it’s also needlessly arduous with its ageing mechanic, with Sifu severely punishing you for any mistakes committed, and the system underlying the game frustratingly obtuse. Playing through Sifu can also feel like being forced to finish your chores when you don’t feel like it—and I certainly felt like I needed to walk away from the game several times to do something else. Anything else, really.

For all the cliches and relentless borrowing of Chinese motifs, there are other aspects of Sifu I adored, such as its environments and spaces. The Club levels, for instance, are reminiscent of the bustling nightlife in China—a side of the country that’s rarely seen, if any at all, in contemporary games and popular media, where depictions of the country are more or less depicted as pastoral scenes of rural countryside during imperial China, occupied by poor facsimiles of people with mock Chinese accents. Then there are the Museum levels, which are adorned with both traditional and modern art. Sifu has the potential for immense splendour, and as I’ve mentioned in my previous piece on Sifu, it’s clear that at least some level of care has been invested into the game and all its set dressings.

But do all these conversations about race, culture, and appropriation truly matter? It may not, to some players, who just want to play a nifty game about an East Asian fighter punching the bejeezus out of other fighters, and to feel pretty darn good about themselves while doing it, like Jackie Chan from his portfolio of action movies. This is the stereotypical power fantasy that video games have long been peddling, and let’s be clear here: I don’t think this motivation is intrinsically wrong. I love a good, hearty game that would get my adrenaline pumping, and there are more than a dozen writers and content creators covering the game from this angle that you can look to for reviews. The problem, however, with only distilling Sifu purely down to its mechanics and systems, is that criticism from the cultural or socioeconomic perspective has long been overlooked, as if these are less important aspects of the game that don’t deserve as much attention. It somehow implies that mechanics and gameplay are sacrosanct to games, as if that’s all the medium is capable of—a point that we obviously know is not true.

It’s also how we have, time and time again, arrived at the same tired, repetitive, lukewarm and trite conversations about whether white studios can make games inspired by other cultures. It’s also how Chinese and religious paraphernalia have been reduced to plastic trinkets and novelty souvenirs, as seen in the creator kits sent to influencers and streamers by Sifu’s developer Sloclap. If you haven’t seen it yet, the creator kit contains artefacts like joss sticks, prayer beads, an art book that vaguely resembles an martial arts manual that’s haphazardly titled “longevity” in Chinese for some reason, the five-coin tassel used in-game as a life meter that, in real life, is traditionally used as a good luck charm, a Chinese seal and a teapot, I guess, for drinking tea—all of which is remarkably insulting because it appropriates these cultural objects and bludgeons them into marketing tools to be used by the studio.

Yet, what sticks out most to me about Sifu is the sad and pitiful cycles of violence in the game. Unlike roguelikes like Hades, Sifu perpetuates these by constantly forcing its players to experience numerous defeats, with actual progress coming at a glacial pace. Sifu’s pack of standard-issue goons would occasionally taunt you with catch phrases like, “You’re so pitiful!”, or “You must love defeat!” and I suppose these are the sort of phrases that should inspire the player into leaping right back to action, and slamming a flurry of thunderous punches into the guts of these sneering mobsters. But more often than not, this doesn’t happen in Sifu; you would die over, and over, and over again till your hair greys and your vitality erodes. Imagine spending several lifetimes fighting with zero recourse or purpose. Even if some revenge movies conclude with the hero immeasurably broken, there is at least some measure of vulnerability or raw, heart-wrenching emotions on display, or even personal epiphanies to be had, but Sifu is bereft of these in its story or presentation. In this aspect, Sifu has really learnt nothing at all.

Edit: We clarified the meaning of the phrase 'sifu' and its use in mainland China.