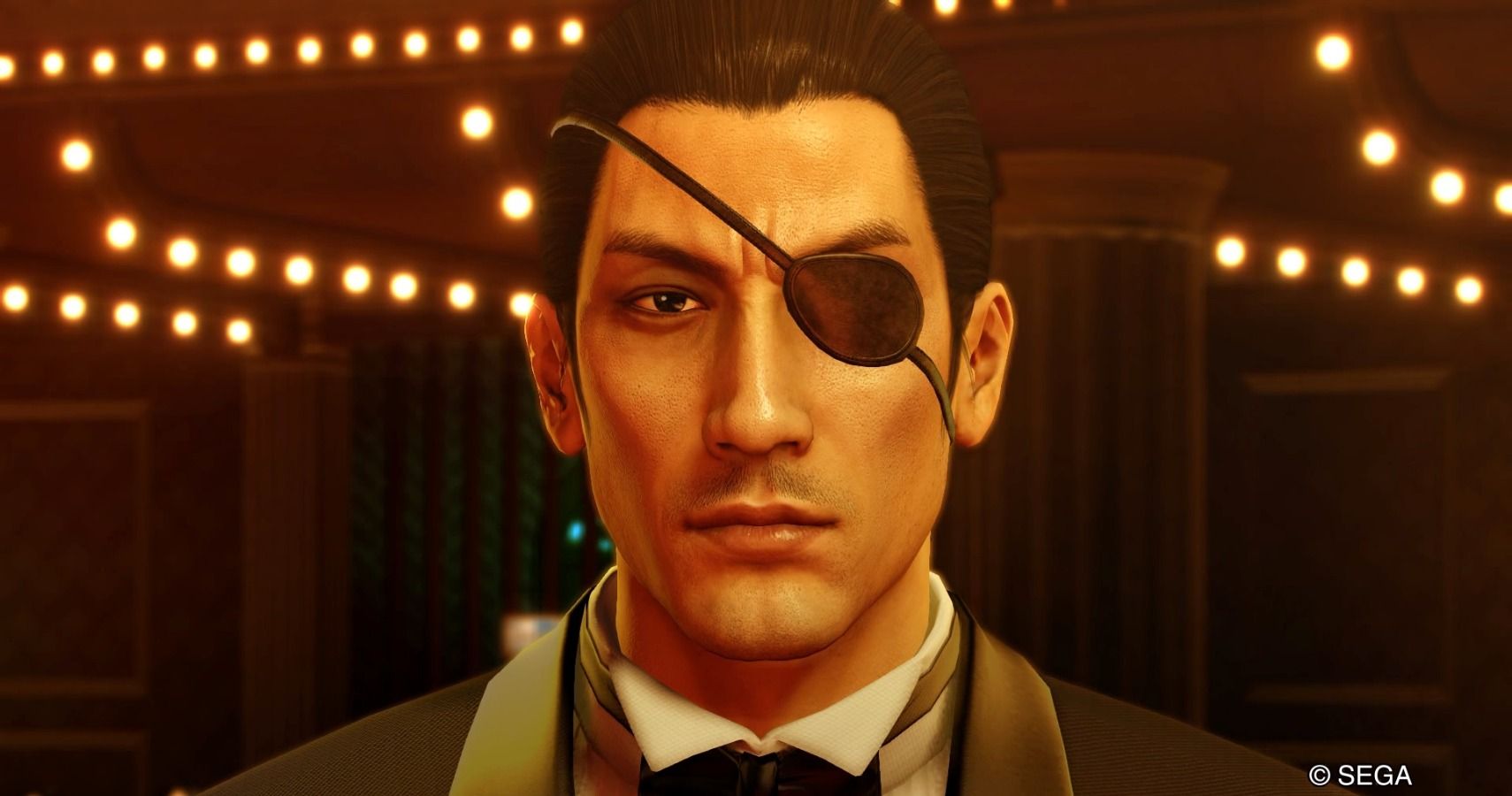

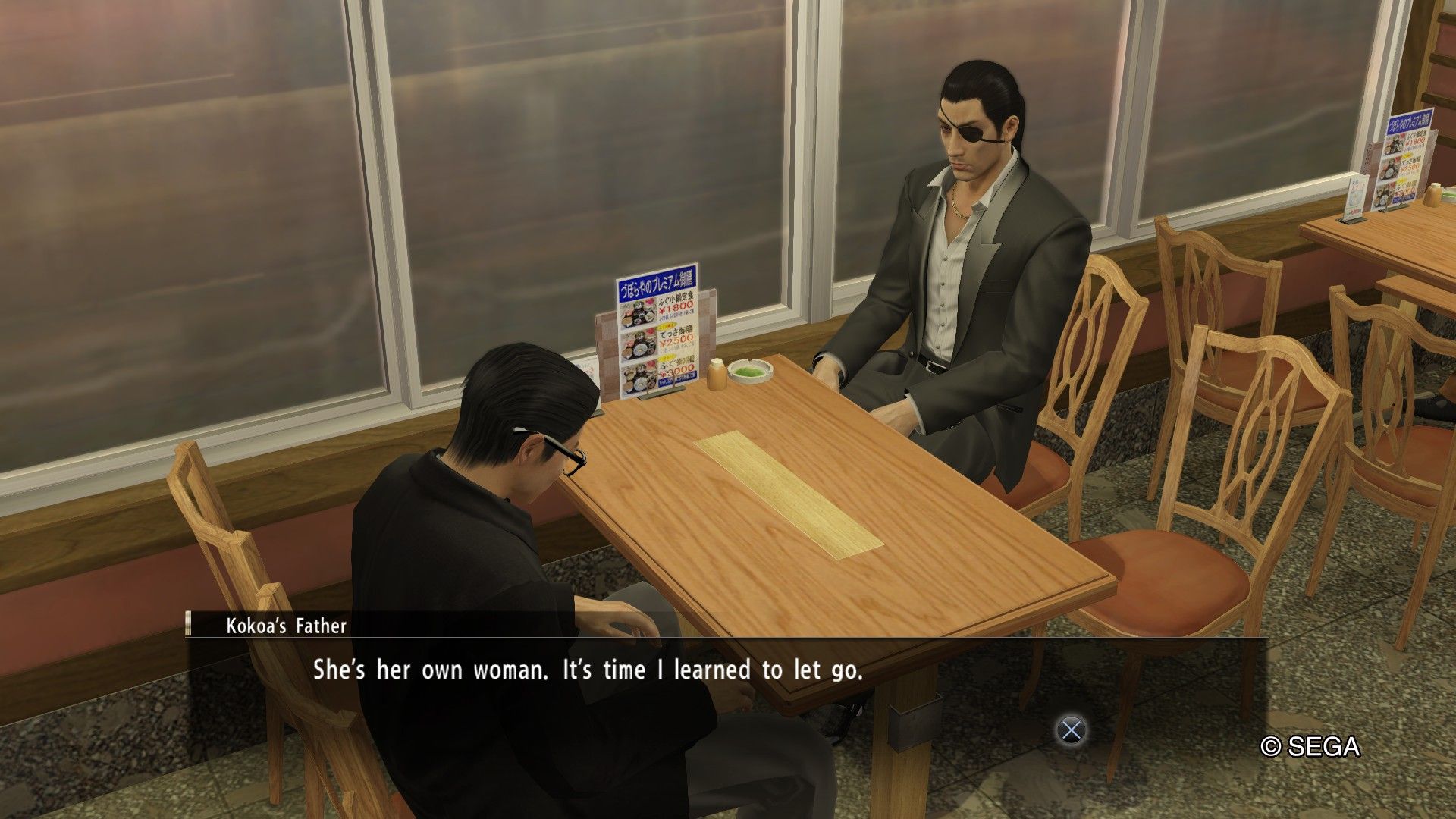

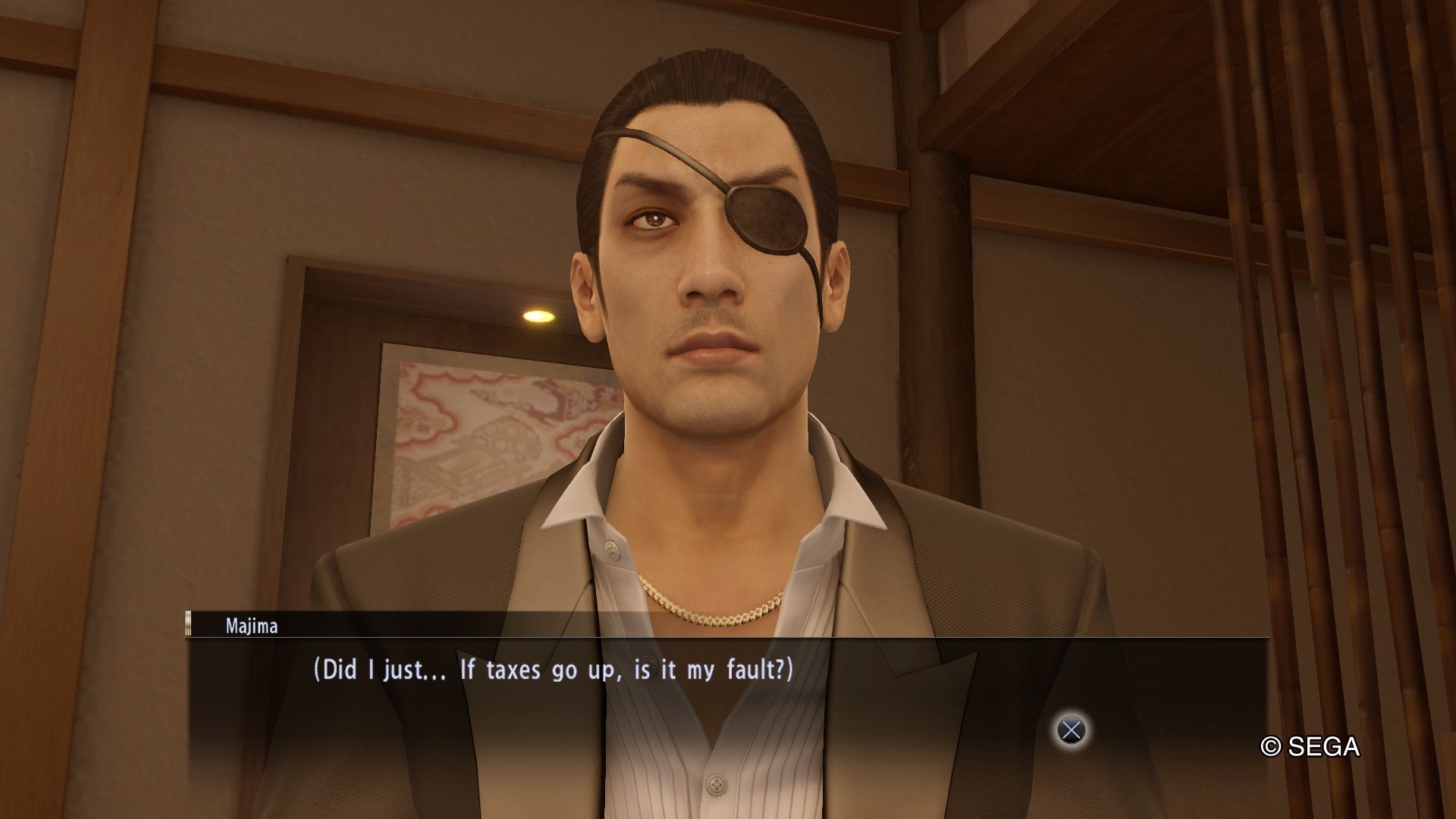

What has Majima gotten himself into this time? He’s sat next to a girl, who’s sat directly opposite her father. “I told you he had an eyepatch,” she’s telling him. “And a ponytail, and that he gives off this intense aura of death.”

Dad’s not bothered about the missing eye or the vague scent of murder, though. He just doesn’t believe this is the guy his daughter is dating.

If you asked me how many people in Osaka fit the Majima bill, I’d say zero with almost outlandish confidence. And yet somehow Koko-chan has managed to find him approximately ten minutes before having to slowly watch her intricate lies unravel in front of her overbearing dad. “Will you be my boyfriend?” she asks. Majima’s not weirded out. He’s not sleazy, or a prick. He’s just like, “What?!” And then he hears her out before deciding, “sure, I’ll help.”

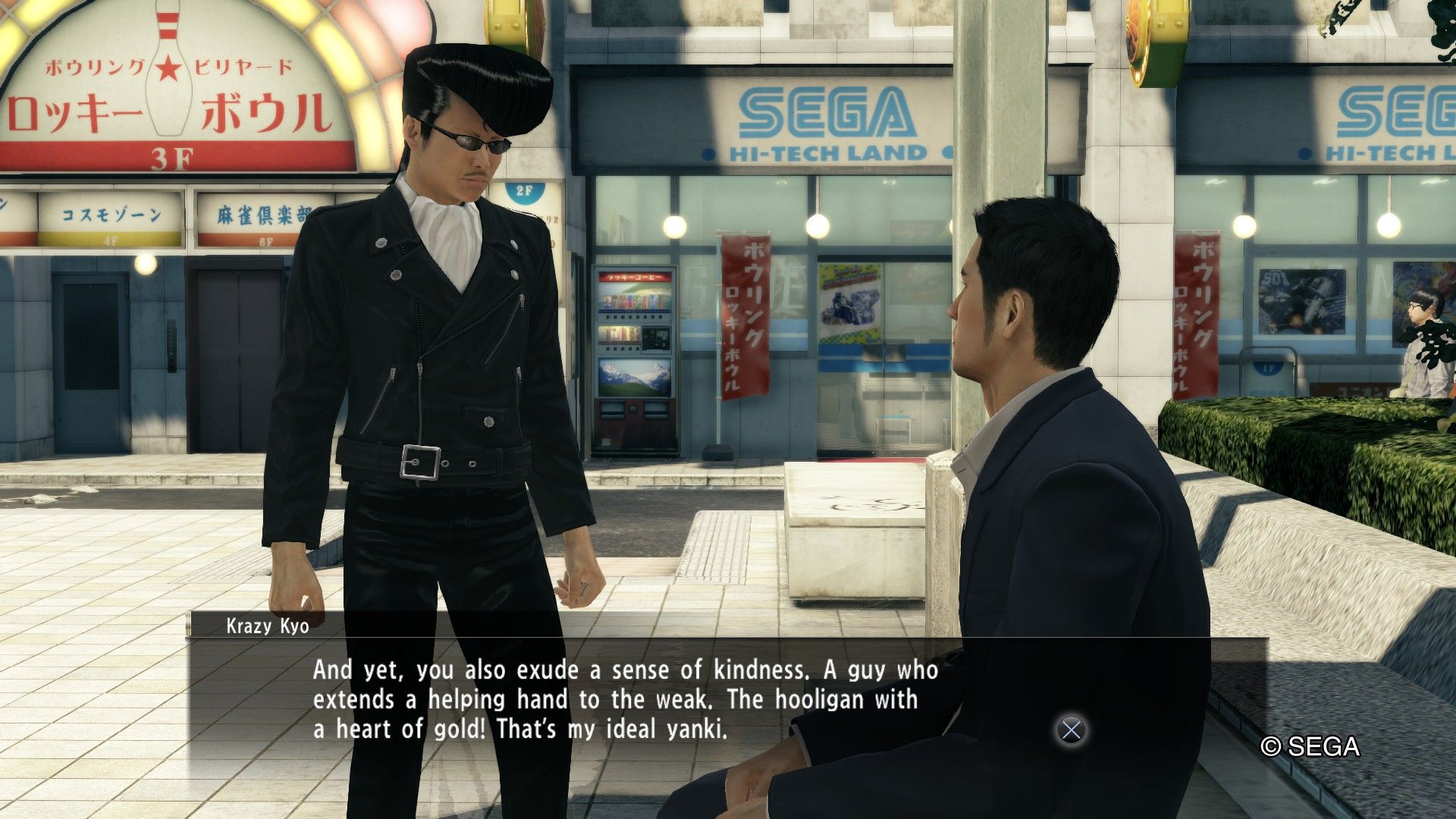

There’s something uniquely special about the way little isolated stories like this one unfold in Yakuza Zero. On one hand, they’re completely at odds with the main narrative of the game. Two ex-yakuzas incapable of escaping their past, vying for redemption due to some self-imposed duty to someone they feel they owe their lives to. Fists of fury; katanas abound; adrenaline-fueled bloody bouts with people bearing the largest Oni tattoo you’ve ever laid eyes on. But what’s that? You’re not a real punk band? Stop the train. I can help you walk the walk — when you get up on stage, address the crowd in English, yeah? I’ll stick around. Miraculously, I’ve got the time.

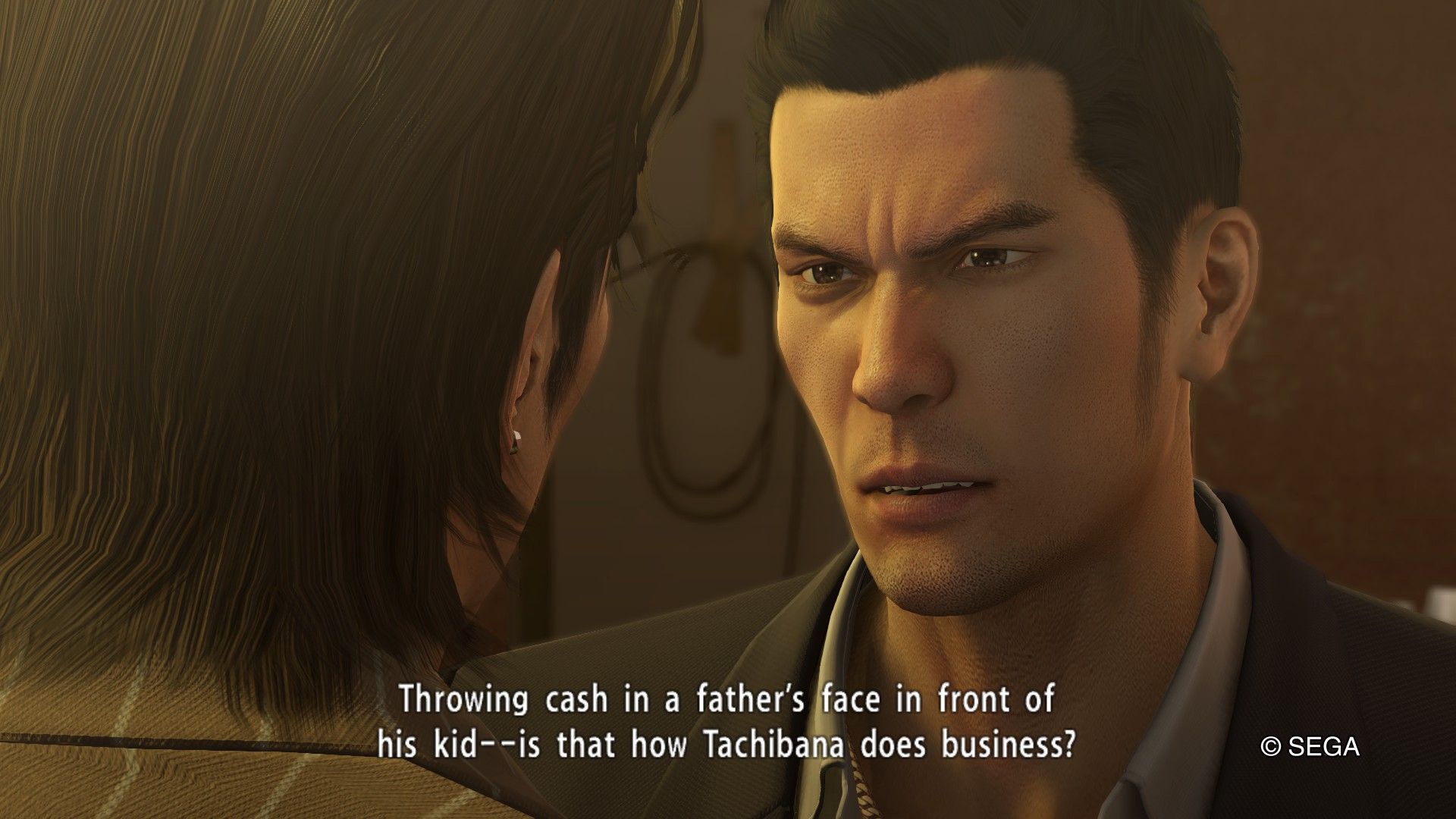

It’s no secret that Kiryu and Majima are hugely beloved among Yakuza fans. I’m still relatively new to the series, but I’d been hit with a “That’s rad!” GIF at least a hundred times before I ever even booted it up. But I think the reason people are so fond of these characters goes far beyond clever dialogue and a compelling narrative. Kiryu is more than the strong protagonist who it’s fun to beat people up with, and Majima isn’t just the loose cannon who can turn an atmospherically dead ballroom on its head and launch it into the stratosphere.

Above all, these two characters are evidently and empathically human. They’re old-school mobsters in some ways, collecting debts with bare and bloodied knuckles while being extra careful not to stain their designer kicks. At the same time, they’re not defined strictly by their ties to Tokyo and Osaka’s gangland — if anything, Zero takes pains to show that they are kind, vulnerable, and deeply emotional. I’m thinking of the flashback sequence where Kazama tells Kiryu and Nishiki that they can’t join the yakuza. Until this point we’ve seen Kiryu be stern, short-spoken, and almost scarily measured. And yet here he kneels, screaming above the howling thunderstorm, furious tears mixing with raindrops and streaming down to the ground beneath him. He is unequivocally hysterical. This kind of vulnerability isn’t something we often see in male characters. And yet it is a core part of both Kiryu and Majima, who will cry, and show affection, and hide their faces from an irritated elderly person like a dog does once you’ve found out it’s gone and shat in the kitchen again.

I love that a kid has his game stolen, and the thief has it stolen from him, and then that thief gets nicked. And then you finally find the last robber and punch his teeth in, and it turns out it’s the kid’s dad, who decided he’d steal the game to give to his son. I love that there are three drunk guys harassing a taxman, and after you save him he asks you for advice on how to increase taxes without upsetting people — and then afterwards you’re like, “shit, did I just help the government increase tax?” I love that a producer tries to kick off because he reckons the director’s a dirtbag, but then you realize the director actually just puts on a facade to keep everyone’s passion ticking, and he’s actually a pretty sound dude beneath all the pretentious pizazz.

All of these little subplots are so endemic to Yakuza’s ultimate success, because they allow its world to become steeped in humanity, in petty squabbles and small victories. On one hand they serve as a reflective surface — Kiryu and Majima witness these events and become far more obviously human as a result. Their experiences resonate with yours, and so it becomes far easier to become invested in the parts of their life that are slightly more sensationalized. I’m not sure about you, but I’ve never been in the yakuza — but because I’ve made an arse of myself on dates and have drunkenly offered my advice on how to fix the taxation problem to people who have a grand total of zero interest in listening to me, it becomes a bit easier to buy into all of the gangs and shootybangs stuff.

On the other hand, it makes the world itself feel significantly more lived-in. I don’t think I have ever played anything that is so tangible — last night I walked along the Sotenbori boardwalk and was reminded of last year when me and my mate sat there draining cans of cheap beer. It’s not just artistically impressive or visually accurate in terms of how well it represents its real-life counterpart (called Dotonbori, not Sotenbori). It’s so much more. Meandering through tight-knit nightlife districts where the paths are too narrow for two people to stand next to one another; wandering along neon-lit roads amid the chaos of post-midnight Tokyo; blending in to the hustle and bustle of city life as people flock from shop to shop, going about the same daily routine that city-slickers adhere to outside of Yakuza Zero. These are all frankly incredible aspects of making a virtual city genuinely resemble a real one, but they are still ultimately artificial. It’s the humanity that bleeds into conversations — not with main characters, but with the idle chatter you exchange with inconsequential NPCs — that makes this place feel truly real. It’s the substories that make the city complete, as opposed to the taxis and skyscrapers, and the massive canal that’s so nice to look at after the sun goes down.

Yakuza Zero is unlike any other game I’ve played. Not just because of its compelling narrative, or three-dimensional characters, or brilliant art. It’s the fact it feels as if the people inhabiting its world are genuinely living in it and making mistakes. It’s the fact that most of its cast are helpless, to an extent, and just need a dig-out or pick-me-up to get back on their feet. Most importantly, though, it’s the fact that you, a bonafide gangster who’s bang smack in the middle of a criminal conspiracy, are genuinely kind enough to help them out. And not artificially kind, either. It’s never all sunshine and rainbows for Kiryu and Majima, and your benevolence usually manifests in the form of blood and broken bones. It’s that genuine kindness that comes from unpretentiously wanting to do something sound for someone, and doing it in a way that isn’t insincere or in the interest of a reward. That, to me, is why Yakuza’s substories are perhaps the most human tales I’ve ever seen a video game tell. Given how high they’ve set the bar, I reckon that statement will remain true for quite some time.